Vol. 77/No. 22 June 10, 2013

|

| Courtesy Raúl Alzaga Manresa |

| Left to right: Raúl Alzaga, Ricardo Fraga, Cuban revolutionary leader Raúl Castro and Carlos Muñiz during Antonio Maceo Brigade’s first visit to Cuba in 1977-78. Alzaga, Fraga and Muñiz were founders of brigade. Second from the right is Vilma Espín, president of Federation of Cuban Women. Muñiz was killed in Puerto Rico by Cuban counterrevolutionaries in 1979. |

|

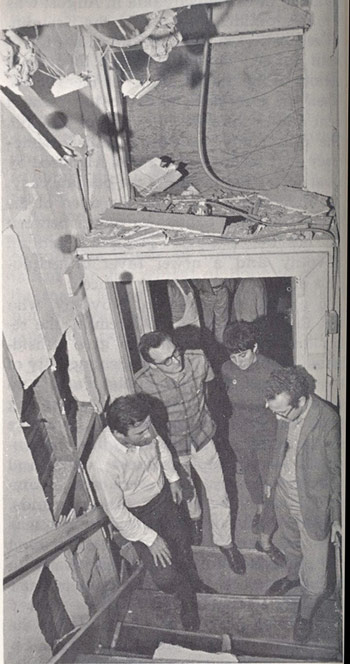

| Entrance to Socialist Workers Party hall in Los Angeles, Oct. 16, 1968, after bombing by United Cuban Power. |

Recently released and heavily redacted FBI documents provide more evidence that the U.S. government remains determined to conceal what it knows about the killing of Muñiz, a supporter of the Cuban Revolution and independence for Puerto Rico. Ricardo Alarcón, member of the Political Bureau of the Communist Party of Cuba, drew attention to the ongoing fight at a youth conference in Havana in solidarity with the Cuban Five at the end of April, the 34th anniversary of Muñiz’s murder.

The Cuban Five are revolutionaries framed up and jailed in 1998 by Washington for gathering information on counterrevolutionary Cuban exile groups based in Florida — including some that belonged to the Coordination of United Revolutionary Organizations, the umbrella group widely believed responsible for the assassination of Muñiz.

Since the 1960s Cuban exile paramilitary organizations have carried out scores of bombings, assassinations and other attacks on U.S. soil — from Miami to Los Angeles to New York. And they have been able to function with virtual impunity and tacit backing of the U.S. government and its cop agencies.

The most recent FBI documents related to the Muñiz assassination were released in February and March this year. Along with others previously released since October 2011, they provide evidence that “the FBI might have known about the plans to kill Carlos and did nothing to stop it,” Raúl Alzaga Manresa, a close collaborator of Muñiz and leader of the committee, said in a phone interview from San Juan May 25. “The new documents indicate the FBI has a whole file on the case they have still not released.”

One of the documents, a 1980 FBI memorandum obtained under the Freedom of Information Act at the request of the Committee of Friends and Family of Carlos Muñiz Varela, reveals that the cop agency had “informants and an asset” inside the Coordination of United Revolutionary Organizations.

From Cuba to Puerto Rico

Muñiz’s story is an important part of the history of the movement in solidarity with the Cuban Revolution.In 1961 Muñiz’s mother sent 8-year-old Carlos and his sister Miriam to the U.S., believing false rumors spread by the CIA and the hierarchy of the Catholic Church that Cuba’s revolutionary government headed by Fidel Castro was going to forcibly separate children from their parents. They joined some 14,000 children enticed to leave Cuba as part of the CIA-orchestrated Operation Peter Pan. She soon reunited with her children and moved to Puerto Rico.

As a university student Carlos joined the fight for independence for Puerto Rico, a U.S. colony, and participated in the labor movement there. In 1974 Muñiz was part of a group of young Cubans in Puerto Rico and the U.S. who questioned their parents’ hostility to the revolution. They founded Areíto magazine, which promoted normalizing relations with Cuba.

In December 1977 Muñiz and Alzaga helped organize a group of 55 young Cubans who grew up outside the island to visit Cuba. The trip led to the creation of the Antonio Maceo Brigade, which organized young Cubans in the U.S. and Puerto Rico to demand Washington normalize relations with Cuba.

The trip opened the door for other Cubans who had left after the revolution to visit the island. In 1978 the Committee of 75, a group that advocated a dialogue with the Cuban government, was formed and held discussions with Havana. Muñiz helped organize another large group that visited Cuba at the end of the year and along with Alzaga set up Viajes Varadero, a travel agency to facilitate the trips.

This infuriated the U.S.-backed counterrevolutionaries. “Dynamite: the only language of dialogue” were typical of headlines in their publications.

On April 28, 1979, Muñiz was ambushed while driving in San Juan and shot several times.

Julio Labatut, a key figure in the rightist Coordination of United Revolutionary Organizations with close ties to police officials in Puerto Rico, was asked during a 2001 TV interview if he had ordered the assassination of Muñiz. “Don’t call it an assassination,” Labatut told journalist Luis Francisco Ojeda. “It was an execution and it should have been carried out before he was born.”

* * *

On Dec. 11, 1964, in a sign of things to come, a bazooka was fired at the United Nations Headquarters from across the East River while revolutionary leader Ernesto Che Guevara was speaking to the General Assembly. The shell fell harmlessly 200 yards from shore.Andrés Gómez, a leader of the Antonio Maceo Brigade, told the Militant from Miami May 25 that the attacks outside the island really began after the revolutionary government of Cuba decisively defeated U.S.-backed counterrevolutionary bandits in the Escambray mountains of Cuba in 1965.

“Between 1968 and 1969 there were 50 terrorist actions in the U.S., many of them carried out by Cuban Power, headed by Orlando Bosch,” Gómez said. “In the 1970s they carried out 270 attacks of different types in the U.S. and other countries, none of them in Cuba. There were around 90 attacks in Miami alone.”

Among the most well known attacks was the Oct. 6, 1976, bombing of a Cubana airline flight that killed all 73 people on board. That attack was masterminded by Bosch and Luis Posada Carriles. That same year former Chilean diplomat Orlando Letelier was killed in Washington, D.C., by colleagues of Posada, and Santiago Mari Pesquera, son of Puerto Rican Socialist Party leader Juan Mari Bras, was assassinated in San Juan. On Sept. 11, 1980, Cuban diplomat Felix García Rodríguez was shot and killed when his car was stopped at a traffic light in Queens, N.Y.

The Cuban counterrevolutionaries also targeted socialist political parties, groups that opposed the U.S. war in Vietnam, and other organizations that took positions opposing the U.S. embargo on Cuba.

In October 1968 alone Cuban counterrevolutionaries bombed the Los Angeles offices of the Free Press newspaper, the Malcolm X Foundation, the Long Beach Students for a Democratic Society, the Peace and Freedom Party and the Socialist Workers Party.

Cuban rightists target SWP

The Socialist Workers Party was among the frequent targets. SWP candidates called for an end to the U.S. embargo and championed the Cuban Revolution as an example to be emulated by working people in the U.S. and around the world. The party’s headquarters in Los Angeles were attacked at least six times by right-wing Cuban exile groups from 1968 to 1970, as well as its offices in New York City.A dozen Cuban rightists, carrying submachine guns and other weapons attacked the Socialist Workers campaign headquarters in Los Angeles in May 1970, threatening to kill four campaign volunteers and forcing them to lie on the floor. The counterrevolutionaries set fire to the building, but campaign volunteers escaped.

On Feb. 4, 1975, a pipe bomb exploded at the Central-East Los Angeles headquarters of the Socialist Workers Party and the Young Socialist Alliance. At the time of the attack there were 25 people in the offices. Immediate evacuation got everyone out safely seconds before the explosion, which sent debris as far as a block away.

The rightists also attacked businesses that maintained commerce with Cuba and even opponents of the revolution who proposed a dialogue or an end to assassinations and bombings.

Luciano Nieves, who had spent time in prison in Cuba for counterrevolutionary activities, was shot and killed Feb. 21, 1975, in Miami after publishing an article in Réplica announcing that he was willing to return to Cuba to vote in elections there. Between 1981 and 1984 five bombs were placed in the Réplica offices in Miami because of articles by its editor Max Lesnik advocating negotiations with the Cuban government.

Emilio Milián, an anti-communist news commentator at WQBA radio, lost his legs when a bomb exploded in his car April 30, 1976, after he criticized rightist groups for a wave of bombings and assassinations in Miami.

While in a handful of the attacks a few individuals were arrested and served time in prison, in the overwhelming majority no one was ever detained.

“Orlando Bosch, a terrorist and a murderer not just of Cubans but of people from the United States freely walks the streets of Miami,” Ramón Labañino, one of the Cuban Five, noted at his sentencing in December 2001. Bosch died in 2011, but the same is true of Luis Posada Carriles today.

By the 1990s the number of attacks inside the U.S. had fallen off, including in Miami, where growing numbers of Cuban workers and others opposed the violent attacks and favored improved U.S.-Cuba relations.

On Feb. 24, 1996, Cuban pilots shot down two planes flown by Brothers to the Rescue — one of the organizations the Cuban Five had been monitoring — after the group had ignored repeated warnings to stop its provocative flights into Cuban airspace.

While the attacks dropped off in the 1990s they did not end, including in Cuba. A string of six bombings on the island killed Italian tourist Fabio di Celmo and wounded 11 people in 1997. The most recent attack in the U.S., in April 2012, was arson that destroyed the offices of Airline Brokers in Miami, an agency that arranges travel to Cuba. The agency had recently arranged travel for a delegation from the Miami Archdiocese to be part of the pope’s visit to Cuba.

Related articles:

FBI labels Assata Shakur ‘terrorist,’ part of US campaign against Cuba

Who are the Cuban Five?

‘Every worker should support the Cuban Five’

Front page (for this issue) | Home | Text-version home