|

|

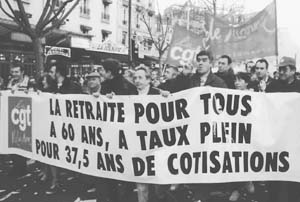

Militant/Nat London

|

| Contingent of workers from the Val-de-Marne march at January 25 action. Banner calls for retirement at age 60 with full pension after 37-and-a-half years of work. |

The bosses' confederation is demanding the unions agree to raise the number of work years necessary for retirement for workers in the private sector from 40 to 45 years, thus raising the retirement age for most workers from the current 60 years to age 65.

The answer to the bosses came January 25, as 300,000 workers hit the streets of Paris, Marseilles, Toulouse, and some 75 other cities. Work stoppages brought the public transportation systems to a halt in Lille, Lyon, Nantes, Rennes, Strasbourg, and Toulouse. Striking workers forced Air France to cancel all short and medium range flights for most of the day. Several Renault auto plants ground to a halt.

Significantly, the actions brought together workers from both the public and private sectors. Large numbers of white-collar workers demonstrated for the first time and the big business media commented on the similarities with the opening stages of the strikes that shook France at the end of 1995. In that conflict, the efforts by the bosses and their government to raise the retirement age of public workers and seriously undermine the public health care system went down to defeat.

On the eve of the January 25 actions, MEDEF head Ernest-Antoine Seillière, who is particularly hated by working people and is known as the "boss of bosses," sarcastically encouraged "those in the demonstrations who are young, employed workers in the private sector to hold a little flag in their hand," implying they would be largely outnumbered by unjustifiably worried retirees and state employees.

But following the actions, MEDEF was put on the defensive and forced to retreat somewhat. Seillière said in a radio interview that he was "especially struck by the impressive character of the contingents, their seriousness, calmness, and dignity." He backpedaled on the bosses' proposal that a full pension only be granted after 45 years of work. "Perhaps we were in fact wrong to announce the whole program," he said, stating they would be willing to initially accept a lower figure. He claimed he was "shocked that there are currently hundreds of thousands of French who have already worked for 40 years, who are under 60, and who don't have the right to retire." Seillière stated he was willing to meet the unions again, as they requested, as long as they presented new proposals.

The MEDEF's top gun was obliged to take into account that 78 percent of the population supported the demonstrations, according to polls taken January 25 and 26, and hesitation in the ranks of the bosses themselves. Two other employers' confederations, representing small companies and independent entrepreneurs, openly questioned the wisdom of Seillière's confrontational strategy, while reaffirming their common goal of pushing back the retirement age.

"We are for dialogue, not for destroying everything," declared Jacques Freidel, president of the General Confederation of Small and Medium Enterprises (CGPME). "We want to arrive at an agreement and therefore not fan the flames or head towards an impasse." But the MEDEF leader remained insistent that raising the retirement age was inevitable.

Massive support by workers

Workers at the Renault auto parts plant in the Paris suburb of Choisy-le-roi did not wait for the official 2:00 p.m. starting time for the plant walkout, which was called by three unions. By 11:30 in the morning, workers were already heading for the plant gate. More than 85 percent of the morning shift left work, and around 75 workers went to Paris for the demonstration that afternoon.

More than 400 construction workers, almost the entire workforce of the Sicra construction company, came to the demonstration. The workers, most of them immigrants from Africa and North Africa, had decided to go on a 24-hour strike "when we heard they wanted to sabotage our retirement," one said. There were delegations from the Peugeot assembly plant in Poissy, the Citroën plant in Aulnay-sous-bois, and the Renault plant in Flins. The Alstom heavy electrical equipment workers were there as were contingents of rail workers, Air France workers, and teachers.

Marc Kinzel, a maritime worker in the port of Marseille said in a phone interview that the action in Marseille was the largest since 1995. Local papers said as many as 50,000 workers took part. Kinzel was part of a contingent of almost 1,500 longshoremen, shipyard workers, and sailors who demonstrated alongside large contingents of public transport workers and workers from SOLLAC, one of the largest steel mills in France.

"One thing that strikes me," said Bernard, an auto worker at Peugeot's Poissy assembly plant, "is that the MEDEF attacked the retirement age of the private sector workers only, hoping that the public sector workers would not come to their defense. That's what they did in 1993 and it worked for them then." Looking around at the different contingents in the demonstration, Bernard--who is one year away from retirement--said, "It looks like they have not succeeded this time. There's more of a sense of unity between public and private sector workers today."

"The unusually strong participation of private sector workers," wrote the daily Le Monde in a front-page article, "has undercut the main argument of the MEDEF, based on the opposed interests of public and private sector workers." Meanwhile, unions representing public sector workers have called for a day of strikes and demonstrations for January 30. Their wage negotiations with the government have been at a standstill.

Bosses' assault

The bosses and the government have repeatedly played on differences between workers in the public and private sectors to advance their assault on the social wage, democratic rights, and conditions on the job. Workers in the private sector were pushed into retreat during the 1980s under sharp attacks by the bosses. Coal mines and naval shipyards were closed, dockworkers laid off, and auto plants and steel mills downsized.

Fascist groups became active publicly, encouraging divisions between immigrant and native-born workers. In 1995, the government's Vigipirate plan, supposedly instituted against "Islamic terrorism," deepened these divisions, with police and machine gun–toting soldiers regularly stopping and searching immigrant workers in the streets.

In 1993, a newly elected conservative government tried to use the retreat of the private sector workers as a stepping-stone for attacks that went beyond simple downsizing. They began to attack the social wage and the rights of the 5.5 million public sector workers in major industries, such as the railroad, gas and electric, telephone and postal, armaments and military naval shipyards, as well as teachers, hospital, and airport workers.

The social wage is particularly important in France. A Renault worker, for example, receives in take home pay only 40 percent of the total labor costs paid by his employer. The rest goes to national funds covering health care, unemployment and retirement, family aid, and public housing construction.

In 1993 the government and the bosses were able to raise the number of years necessary for full retirement in the private sector without a response from workers and their unions. However, subsequent efforts by the conservative government to privatize Air France, create a subminimum youth wage, to freeze wages and raise the retirement age for public sector workers, and to gut the public health care system went down to defeat in the face of determined workers' resistance. The high point of these struggles was in the December 1995 strikes led by railroad workers against the drive by the government of Alain Juppé, leader of the conservative Rally for the Republic (RPR) to raise the retirement age. The massive movement in 1995 drew in few workers employed in private industry or immigrant workers.

Bosses continued to deal blows to the 14.5 million private sector workers during the 1990s, aided by the pressure of high levels of unemployment. Public sector workers, who cannot be fired except for rare disciplinary cases, were less vulnerable to this pressure.

From 1996 to 1999, the number of temporary workers more than doubled, rising to 500,000. In addition, the number of workers on limited work contracts, ranging from a few weeks to 18 months, tripled between 1982 and 1999, reaching 892,000.

The weight of temporary workers is particularly heavy in industry, where they are twice as numerous percentage-wise as they are in the entire workforce. In auto, for example, they represent 8.7 percent of total employment and often half of assembly line workers.

Workers in private industry were dealt another blow by recent legislation that purports to lower the workweek to 35 hours. This has not yet been applied to public sector workers. Implementation of these laws has been negotiated company by company, leaving workers in many enterprises with a poor relationship of forces and more vulnerable than others. Although the law has led to a slight reduction in the workweek, its main aim was to give employers the ability to impose "work flexibility" in shifts and hours.

Interimperialist competition

Despite these successful blows, the employers' organization estimates that overall, "for 10 years France has lost ground in relation to its European competitors," Seillière said January 24. To try to make up for lost ground, MEDEF has stepped forward to take the political lead in pushing for concessions by the unions. The Juppé government lost the 1997 legislative elections to a coalition led by the Socialist Party alongside the French Communist Party and the Greens. The Rally for the Republic has not recovered from its defeat. The right-wing parties are in disarray as well.

The MEDEF launched a campaign a year ago of "social refoundation," seeking to lower the social wage including raising the age of retirement. "In one word, we are standing still," Seillière told a Senate commission on the eve of the workers actions. "Our structural handicaps are weighing us down. French competitiveness requires strong moves forward."

The police announced January 25 that they were reactivating the Vigipirate plan following a bombing attributed to a Corsican nationalist group.

Nat London is a member of the CGT at the Renault auto plant in Choisy-le-roi. Derek Jeffers is an auto assembly worker and member of the CGT at the Peugeot auto plant in Poissy.

Front page (for this issue) |

Home |

Text-version home