Vol. 76/No. 47 December 24, 2012

|

| While statistical measurements of “productivity” and workers’ “real wages” should be taken with a grain of salt, graph illustrates a growing gap between the two, as pressure on profit rates spur bosses to squeeze more from labor while driving down the costs. |

According to the Labor Department’s news release, “payroll employment rose by 146,000 in November.” But the department’s own figures also say that the total number of people employed in the country actually declined by 122,000.

How is this magic trick accomplished? In large part by “disappearing” 350,000 workers from the official workforce, which means they are no longer counted when figuring employment rates. Among them are 166,000 workers the statisticians added in November to a category they consider too “discouraged” in their job prospects to bother counting.

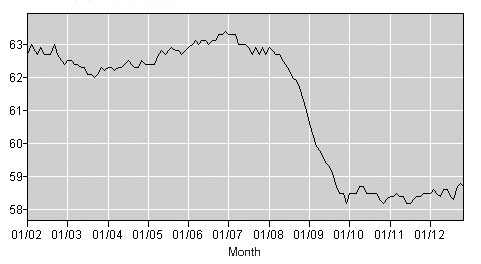

|

| After dramatic decline, employment to population ratio has hovered around same low level for the last three years. |

The employment to population ratio—a straight percentage of the total population that is employed—provides a more accurate gauge of those without work. Unlike the official unemployment rate, it is not easily masked by removing discouraged workers from the job figures or other methods. In November the ratio declined by 0.1 to 58.7 percent, meaning a slightly smaller percentage of the population is working than the previous month.

After a sharp decline of 5 percentage points between 2007 and 2010, the employment to population ratio has hovered around the same spot for the last three years. This represents not only the lowest rate in decades, but an unprecedented amount of time without any sign of even a temporary recovery.

“Many millions of Americans, in particular less-skilled men, are leaving the workforce, a phenomenon the country has never seen before on the present scale,” wrote Jonathan Rauch in a Dec. 5 article in the National Journal titled “The No Good, Very Bad Outlook for the Working-Class American Man.” This situation, he states, might “bring social unrest and class resentment of a magnitude the country hasn’t known before.”

What the statisticians refer to as productivity in U.S. factories increased at a 2.9 percent annual rate in the third-quarter of 2012, its fastest rate in two years, reported the Labor Department. One of the main ways bosses are raising labor productivity—more goods produced in less time—is by making employees work harder, faster, under more unsafe job conditions. Fewer workers are pressed to crank out more work while millions search for work.

“Productivity is rising handsomely, but compensation of workers isn’t keeping up,” writes Rauch. In fact over the past three decades it “has hardly risen at all.” Between 1948 and 2011 productivity rose 254.3 percent, while average hourly compensation has only gone up 113.1 percent, according to the Economic Policy Institute.

“From the end of World War II through about 1980, almost two-thirds of every dollar of income generated by the economy flowed to workers in the form of wages and benefits,” writes Rauch. “Beginning around 1980, workers’ share began to slide and, in the past decade or so, has nosedived to about 58 percent.”

Meanwhile, manufacturing declined in November to its lowest level in more than three years, according to the Institute for Supply Management. While retail trade employment rose by 53,000 last month, in preparation for holiday sales, manufacturing jobs declined by 8,000 and construction by 20,000.

Related articles:

‘Cliff’ or no cliff, workers go to the wall

Front page (for this issue) |

Home |

Text-version home