Vol. 77/No. 12 April 1, 2013

|

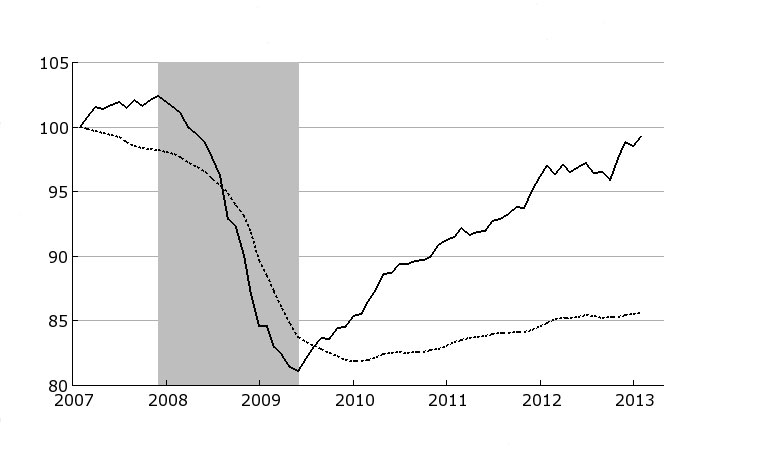

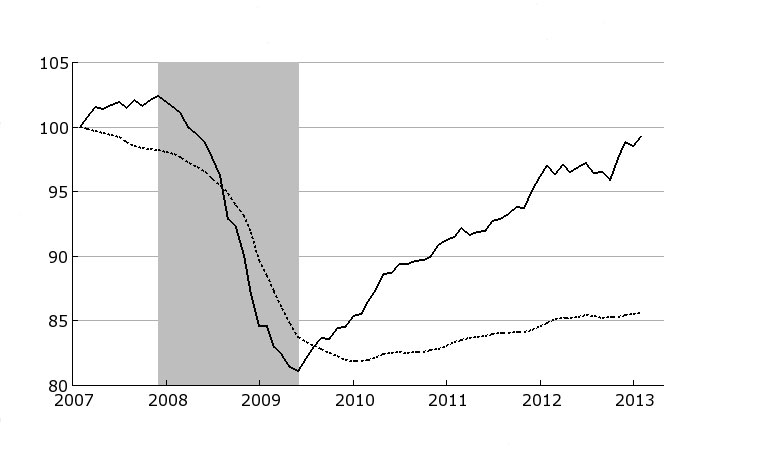

| Growing gap between recovery in production and employment shows U.S. manufacturing bosses’ success in squeezing more from workers’ labor since end of recession. Progress in bosses’ “productivity” drive has made U.S. goods more competitive, laying basis for capturing a larger share of world markets. Trend could lead down the road to expanded hiring by bosses in U.S. to meet demand and opportunities for greater profits. |

|

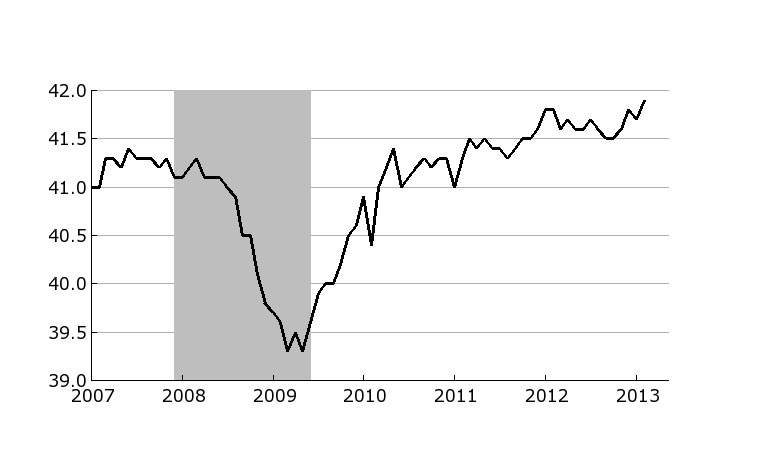

| Length of average workweek exceeded pre-recession levels years ago and has continued to rise as production increases and bosses remain reluctant to expand hiring. |

Through faster line speeds and other “productivity”-raising methods, bosses in the U.S. have increased their competitive advantage on the world market.

U.S. factory production expanded in February for the third straight month, its biggest increase in three and a half years, according to the Institute for Supply Management. Exports increased to a nine-month high and new orders and order backlogs rose sharply.

While the capitalist crisis is marked by a long-term tendency of slowing production and trade worldwide, U.S. companies are outcompeting rivals in Europe. In France, industrial production fell 3.1 percent in the last quarter of 2012 as exports continue to decline. Manufacturing in Germany declined 2012 but expanded over the first two months this year as exports to Asian countries rose.

Manufacturing growth has slowed in China—the world’s second-largest economy. In Japan, manufacturing production, new orders and employment have all been contracting for months.

“U.S. labor costs have been rising more slowly than in other major countries, while manufacturing productivity is near the top in global rankings,” reported a March 6 Bloomberg News article by Caroline Baum. In addition to speedup of production, “cheap natural gas has provided an additional cost advantage,” the article pointed out.

“Output per person,” a basic measure of capitalist productivity, also fell during the recession, but rebounded to prerecession levels within a few months and has continued to rise.

The very modest recovery in manufacturing employment over the last three years marks the first increase of any significance since it plunged with the previous recession of 2001. Over the last 13 years, 5.7 million manufacturing jobs—33 percent of the total—have been eliminated, bringing the workforce in that sector down to about 12 million, the level of the early 1940s.

In Baum’s words, “U.S. companies have become considerably leaner and much fitter in a tough global environment over the last decade.” In their view workers and our livelihoods are the “fat.”

The bosses’ gains at our expense, resulting in expanding U.S. exports, are laying the basis for increased hiring as the pace of productivity gains reach temporary limits. As this has begun to happen, bosses’ reticence to hire is showing up in longer work hours. According to the U.S. Labor Department, the average manufacturing workweek rose 0.2 hours to 40.9 hours, with factory overtime averaging 3.4 hours. During the recession weekly manufacturing hours fell by 2 hours to 39.3.

If current trends continue, manufacturing bosses will hire as they compete with each other to expand production to meet demand and maximize profits.

Front page (for this issue) |

Home |

Text-version home