Vol. 77/No. 35 October 7, 2013

|

“Acts of resistance to the occupying forces or any acts which may disturb public peace and safety will be severely punished,” warned Gen. Douglas MacArthur in his Sept. 7, 1945, proclamation establishing the interim U.S. military government in South Korea. And that’s what workers and peasants faced, as more than 100,000 Koreans were killed over the next half decade (and many more beaten, tortured, or jailed), as the U.S. occupiers and their local collaborators suppressed strikes, land seizures and uprisings.

Meanwhile, north of Korea’s 38th parallel, a Central People’s Committee was established in February 1946, with Kim Il Sung, a leader of the liberation movement against Tokyo’s colonial boot since the 1930s, as chairman. The new workers and peasants government recognized peasant land seizures and organized a sweeping agrarian reform; expropriated the landlords and capitalists, both Japanese and Korean; and carried out other social measures in the interests of working people.

On Sept. 9, 1948, in response to the imposition of the Syngman Rhee regime in Seoul through U.S.-rigged elections, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea was established in Pyongyang.

Korean War

When war erupted between the two governments on June 25, 1950, the U.S. rulers backed to the hilt the Rhee regime’s efforts to reimpose the dictatorship of capital in the north. At the time, many in the U.S. ruling class also hoped their troops could march beyond the Yalu River and strike a fatal blow to the Chinese Revolution, which had triumphed in 1949.Within two days, Washington arranged United Nations Security Council cover to deploy armed forces from the United States and U.S. allies in what President Harry Truman labeled a U.N. “police action” to “suppress a bandit raid on the Republic of Korea.”

On direct orders from Premier Joseph Stalin, Soviet Ambassador Jacob Malik didn’t show up for the Security Council vote, where he would have been able to veto the U.S. resolution. Moscow’s pretext was that it was boycotting the Security Council to protest Washington’s decision to block the People’s Republic of China from U.N. membership. But the real reason — to avert a showdown with Washington — was laid bare less than a week later when the Soviet Union’s turn as Security Council chair came around and Malik’s “principled boycott” abruptly ended.

Over the next three years, some 2 million U.S. soldiers were sent as cannon fodder to Korea, along with more than 160,000 troops from 15 other countries, with the largest numbers from the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and Turkey.

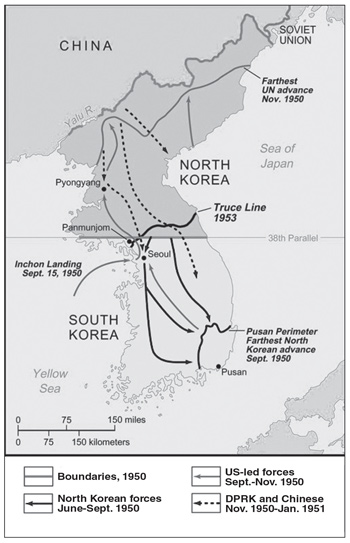

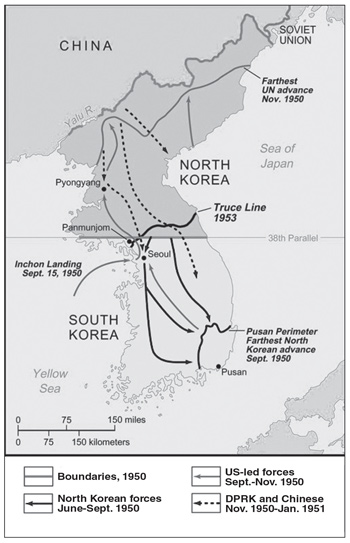

The DPRK’s Korean People’s Army rapidly liberated 90 percent of the peninsula, down to a small southeastern corner of the country that became know as the “Pusan perimeter,” from the name of the coastal city it encircled. When a U.S. regiment arrived by ship in Pusan in mid-July, Korean dockworkers were on strike and refused to offload their weapons. The U.S. troops either unloaded the equipment themselves or forced Korean longshoremen to do so at gunpoint.

Rhee and his chief cronies fled Seoul as soon as the fighting began, with the top officer corps trailing behind two days later. By the day after that, June 28, less than a quarter of South Korean troops could be accounted for, and most of their heavy weapons and equipment had been abandoned, destroyed, or captured.

Unburying the truth

The tenor of much of the war coverage in the U.S. capitalist press is illustrated by a couple of July 1950 dispatches by Hanson Baldwin, the Pulitzer Prize-winning military editor for the New York Times. Calling the DPRK troops “invading locusts,” Baldwin wrote, “We are facing an army of barbarians in Korea, but they are barbarians as trained, as relentless, as reckless of life, and as skilled in the tactics of the kind of war they fight as the hordes of Genghis Khan.”Acknowledging outrage among Koreans at the “women and children slain by American bombs” in the war’s first weeks, Baldwin added that the U.S. armed forces must show that “we do not come merely to bring devastation” but instead convince “these simple, primitive, and barbaric people … that we — not the Communists — are their friends.”

When CBS radio correspondent Edward R. Murrow posed the question in a taped broadcast how Koreans in “villages to which we have put the torch” during the flight to Pusan might view “the attraction of Communism,” top network executives refused to air it.

Aside from the pages of the Militant, one of the few places factual information could be found in those years, much of the truth about what had happened in Korea only began to come out under the impact of the fight for national reunification by the Vietnamese people in the 1960s and 1970s, and the worldwide movement against the U.S. war there.

These revelations were also spurred by a new rise of struggles in South Korea against the U.S.-backed tyranny, above all the 1980 Kwangju rebellion in which thousands of armed workers took over the city. Hundreds were killed in Kwangju by Seoul’s police and troops, aided by U.S. forces there, but a few years later the reverberations of that battle and others across South Korea brought down the dictatorship of Chun Doo-hwan.

The 60th anniversary of the Korean War has spurred the publication of several new books telling more of the truth about its roots and consequences. One is The Korean War: A History (Modern Library, 2010) by Bruce Cumings, who has written other valuable accounts over the past 30 years. This summer has seen the release of Brothers at War: The Unending Conflict in Korea (Norton, 2013) by Sheila Miyoshi Jager. Another useful book (especially regarding conditions facing U.S. and other “U.N.” troops), published on the 50th anniversary, is: MacArthur’s War: Korea and the Undoing of an American Hero (Simon & Schuster, 2000) by Stanley Weintraub, who was a GI in Korea during those years. Much of the information in these articles comes from these books, as well as from the pages of the Militant since 1945.

In addition, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Korea — established in 2005 by the South Korean government to investigate atrocities before, during, and after the war, and dissolved five years later for doing its job too well — uncovered evidence of the murder of between 100,000 and 200,000 people by South Korean authorities between 1945 and 1953, as well as 138 massacres by U.S. forces during the war.

The commission was spurred in large part by the widely reported exposure in 1999 of a July 1950 massacre by U.S. troops of some 400 civilians in the village of No Gun Ri, one of many such atrocities by South Korean and U.S. forces covered up for half a century by the bourgeois press in the United States and elsewhere. Among the documented cases committed by South Korean forces during their flight from Seoul in July 1950 was the slaughter and mass burial of some 4,000 people in the city of Taejon, site of one of the most hard-fought battles during the opening weeks of the war.

Invasion at Inchon

In September 1950, as South Korean and U.S. forces were facing defeat, some 80,000 U.S. Marines invaded at Inchon Harbor near Seoul. Over the next several weeks, the armed forces of the DPRK organized a retreat north from the Pusan perimeter.But General MacArthur’s bombastic promise to U.S. troops that they would be “home by Thanksgiving,” and then “home by Christmas,” was a sham. As U.S. soldiers approached the Yalu River, separating Korea from China, some 260,000 Chinese troops crossed the border to aid the DPRK’s forces in pushing back the invasion. What’s more, MacArthur — who himself never spent a single night in Korea during the war, flying back to the comforts of Tokyo after each visit — hadn’t equipped U.S. soldiers for the bitter-cold Korean winter. Many suffered from frostbite, and their weapons and other equipment wouldn’t function.

In early 1951, at a low point in the morale of U.S. forces, Gen. Matthew Ridgway took over operational command and managed to hold on to a line at roughly the 38th parallel. The murderous U.S. bombardment of North Korea described in the first article in this series — leveling Pyongyang and scores of other cities, towns, and villages — had not broken the will of the Korean people.

Nor had the Truman administration’s threats, in face of the aid being given to Korean liberation forces by Chinese troops, to unleash nuclear weapons. “We will take whatever steps are necessary to meet the military situation,” Truman said at a Nov. 30, 1950, press conference — including attacks on China itself and “active consideration” of using the atomic bomb.

So in July 1951 the U.S. government agreed to begin cease-fire talks with the DPRK. As the war became increasingly unpopular among working people in the U.S. over the next two years, the new Republican administration of Dwight Eisenhower finally signed an armistice at the Korean village of Panmunjom near the 38th parallel on July 27, 1953.

By most estimates, more than 4 million people were killed in the U.S.-organized war, including at least 2 million civilians. The big majority of deaths were of Koreans — some 10 percent of the peninsula’s prewar population — with hundreds of thousands of Chinese killed or wounded as well.

More than 40,000 soldiers from the U.S. and other allied countries were killed; some 115,000 wounded; and more than 7,500 U.S. troops still listed as missing in action. Proportionally, the highest rates of deaths and wounded were among troops of the so-called U.N. forces sent as cannon fodder by allied governments to help give cover to Washington’s war. Of the first 300-man unit of troops from Turkey to see combat, only 45 survived; altogether the casualty rate for Turkish troops (deaths and injuries) was 20 percent. Rates between 13 and 32 percent were also suffered by troops from Belgium, Ethiopia, France, Colombia, Greece, Luxembourg and the Netherlands.

How the ‘Militant’ campaigned

The Militant campaigned to halt the imperialist war in Korea. As the socialist weekly had done in covering struggles by Korean working people over the half decade prior to the war, it scoured the bourgeois press for whatever facts slipped through and ran accounts by GIs or merchant seamen who had ended up in Korea.Among the well over 200 articles, editorials, and statements by Socialist Workers Party candidates during the first year and a half of the conflict alone, some of the headlines read: “SWP Candidate Hits Intervention in Korea,” “Jim Crow in Korea,” “The Real Role of the UN,” “War Reporters Describe U.S. Atrocities in Korea,” “Labor Should Demand: ‘No War with China!’,” “U.S. Army Censor Holds Reporter ‘Incommunicado’,” “Millions in Korea Flee U.S. Bombs,” “Rhee’s Soldiers Massacre Entire So. Korea Village,” and “Korea War a Year Old — Stop the Slaughter Now — Acheson Compelled To Admit ‘Police Action’ Is Real War.”

In 1950 and 1951 the working-class newsweekly featured three letters from Socialist Workers Party National Secretary James P. Cannon to President Harry Truman and members of the U.S. Congress.

“This is more than a fight for unification and national liberation,” Cannon wrote in the first letter, dated July 31, 1950, just a few days after U.S. troops entered the combat. “It is a civil war. On the one side are the Korean workers, peasants and student youth. On the other are the Korean landlords, usurers, capitalists and their police and political agents. The impoverished and exploited working masses have risen up to drive out the native parasites as well as their foreign protectors. …

“Your undeclared war on Korea, Mr. President, is a war of enslavement. That is how the Korean people themselves view it — and no one knows the facts better than they do. They’ve suffered imperialist domination and degradation for half a century,” Cannon wrote, “and they can recognize its face even when masked with a UN flag. …

“I call upon you to halt the unjust war on Korea. Withdraw all American armed forces so that the Korean people can have full freedom to work out their destiny in their own way.”

Cannon’s second letter was written on Dec. 4, 1950, after Chinese troops had come to the aid of Korea and amid Truman’s nuclear saber-rattling. “Your reckless adventure in Korea has brought this country into a clash with the 500 millions of China and threatens an ‘entirely new war,’” Cannon wrote. “Your proposed solution, Mr. President, is a threat to repeat the atrocities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki by using the atom bomb in Korea. … Stop the war NOW!”

Three years later, after the July 1953 cease-fire, the Militant hailed the Korean people’s defeat of Washington’s war aims and drew lessons from imperialism’s bloody assault. “Giant armies have been pitted for three years in ferocious combat against each other; unsurpassed concentrations of firepower have been used; casualties have run into the millions and property destruction has been almost total,” said an article in the Aug. 17 issue.

The cease-fire in Korea, the Militant said, registered “the fact that the United States, the foremost capitalist power and chief military spearhead of world imperialism, for the first time in its history has come out of a war without a victory.”

U.S. refuses to sign peace treaty

Over the six decades since the 1953 armistice in the Korean War, the U.S. government has nonetheless maintained an official state of war on the peninsula, refusing to this day to sign a peace treaty with the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. Among other things, Washington maintains 28,500 troops in South Korea and conducts provocative joint military exercises with Seoul every year.As part of Washington’s efforts to isolate and strangle the people of North Korea, this year alone it has taken the initiative to slap the DPRK with two new sets of economic and financial sanctions, adopted Jan. 22 and March 7 by the U.N. Security Council. These sanctions tighten restrictions on the DPRK’s banking transactions and access to trade credits, as well as expanding the list of banned imports. The measures also imposed mandatory interdictions — aka piracy — of North Korean ships and aircraft suspected of transporting such proscribed goods.

Since mid-July Panamanian authorities, at Washington’s bidding, have detained a North Korean cargo ship sailing from Cuba as it prepared to cross the Panama Canal. The government of Panama, saying it acted on a “tip” from U.S. intelligence that the Chong Chon Gang was smuggling drugs, now claims the cargo violates the U.N. arms embargo. The vessel was transporting sugar, as well as Cuban arms for repair in North Korea.

Washington’s pretexts for the two most recent rounds of sanctions were the DPRK’s successful launching of a satellite into orbit last December and a nuclear weapons test in February. The hypocrisy and imperial arrogance of the U.S. rulers are shown by two facts: (1) of the more than 1,000 satellites in orbit as of May 2013, some 43 percent are of U.S. origin — 12 percent openly for military purposes; and (2) of the 2,053 nuclear tests since 1945, 1,032 have been conducted by Washington and three by Pyongyang.

What’s more, Washington openly maintained tactical nuclear weapons on South Korean territory until 1991. And nine U.S. nuclear-armed submarines prowl the Pacific, each one outfitted with missiles (with a range of more than 5,500 miles) and nuclear warheads equal in their heinous payloads to some 6,000 times the imperialist holocaust unleashed against Japanese and Korean residents of Hiroshima in August 1945.

As the Socialist Workers Party National Committee wrote in a recent message to the Central Committee of the Workers’ Party of Korea on the 65th anniversary of the founding of the DPRK, “The people of Korea, Asia, and beyond have no interest in these monstrously destructive weapons and aspire to a world free of them once and for all. …

“US troops and weapons out of Korea and its skies and waters! For a peninsula and a Pacific free of nuclear weapons!

“Korea is one!”

Front page (for this issue) |

Home |

Text-version home