Vol. 78/No. 1 January 6, 2014

|

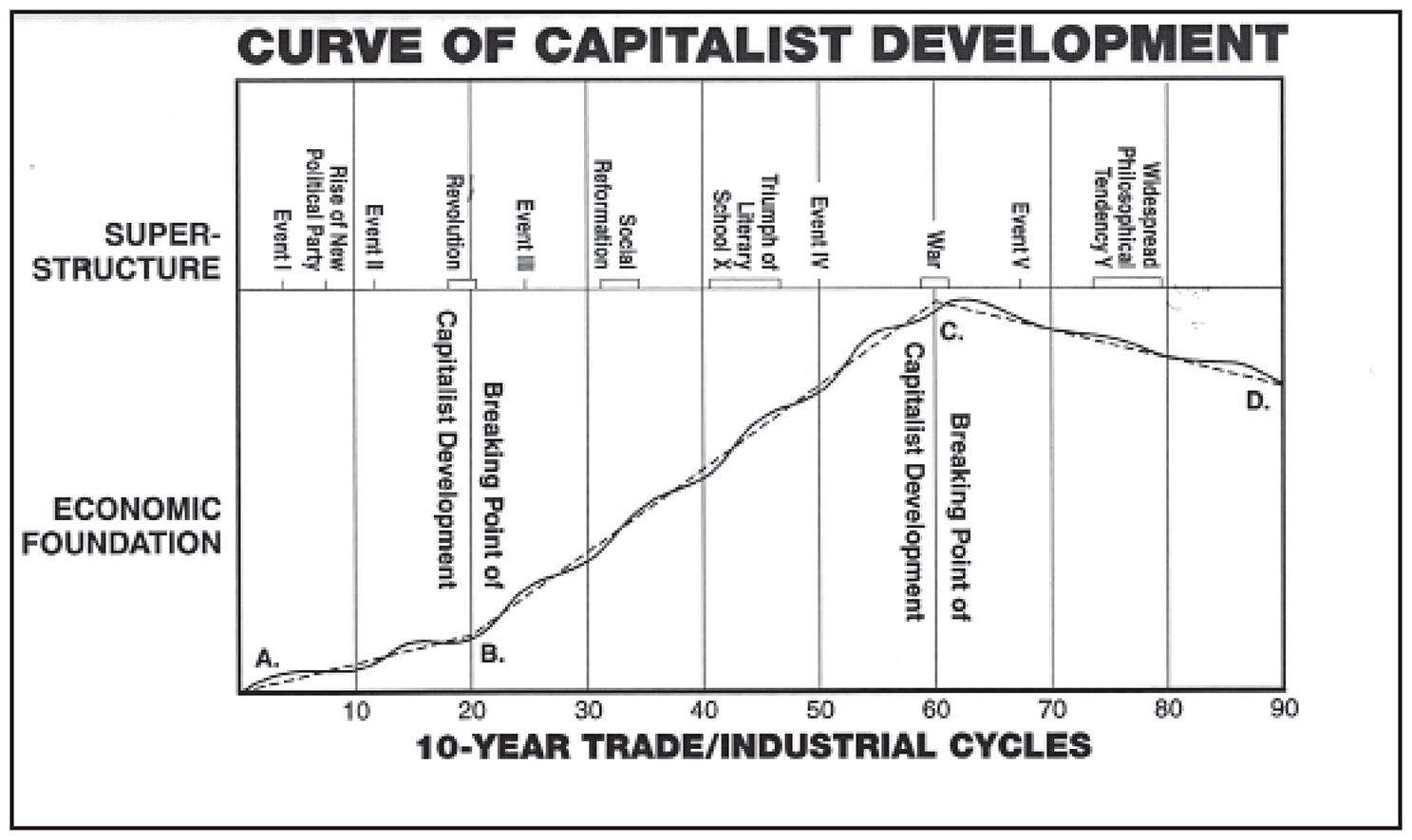

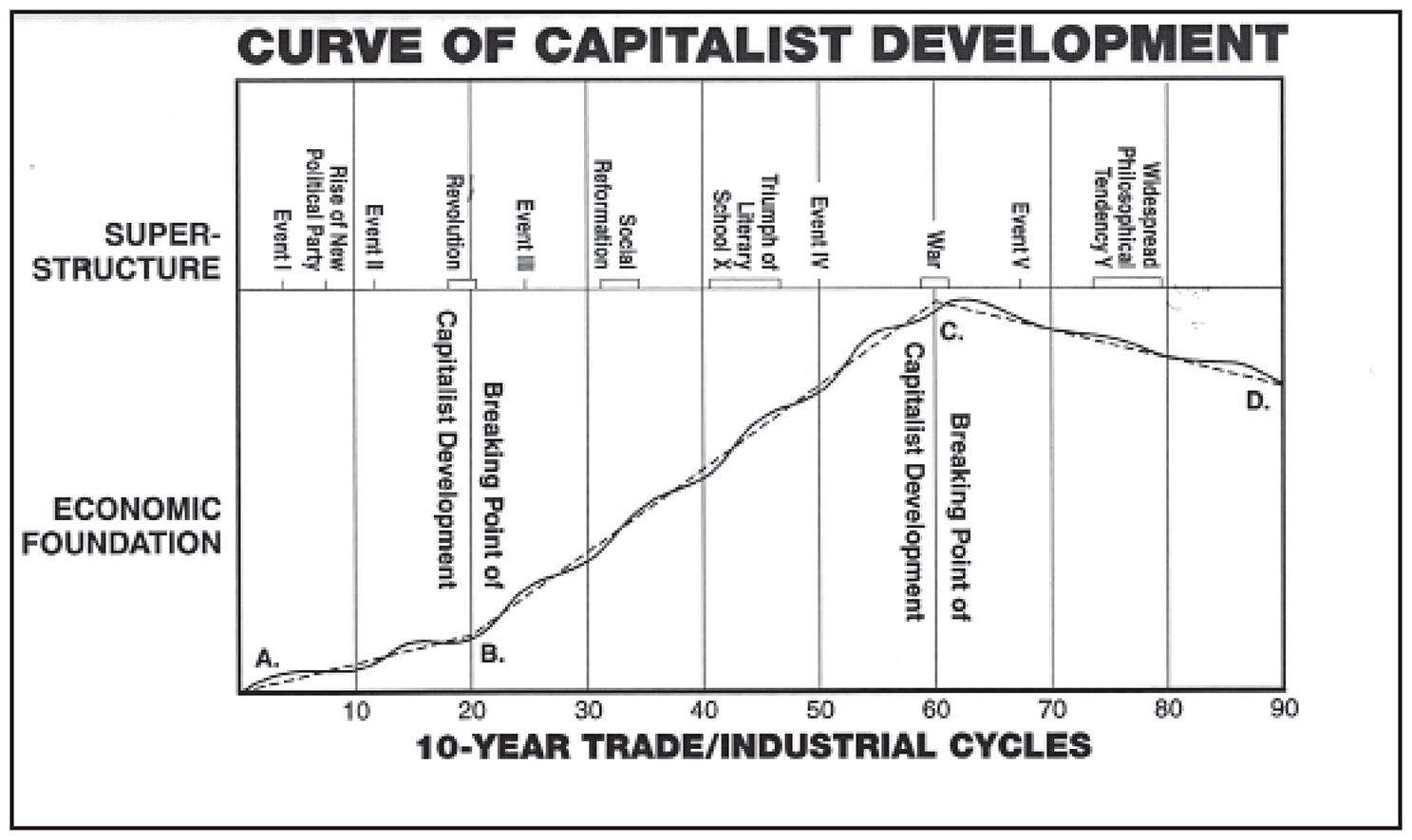

| Schematic chart used by Trotsky to illustrate curve of capitalist development, juxtaposing major political and historical events with shifting economic growth and decline. |

Reprinted below is an excerpt from “The Curve of Capitalist Development,” a letter by communist leader Leon Trotsky that was published in the Soviet Union in 1923. The letter addresses the practical implications for class-conscious workers of discerning the difference between the periodic ups and downs of the business cycle and the long-term ascent or decline in the curve of capitalist development. This question was discussed by the international communist movement in the half decade after the 1917 Russian Revolution. Trotsky’s letter is printed in New International no. 10. Copyright © 1994 by New International. Reprinted by permission.

BY LEON TROTSKY

Oscillations of the economic conjuncture (boom-depression-crisis) already signify in and of themselves periodic impulses that give rise now to quantitative, now to qualitative changes, and to new formations in the field of politics. The revenues of possessing classes, the state budget, wages, unemployment, proportions of foreign trade, etc., are intimately bound up with the economic conjuncture, and in their turn exert the most direct influence on politics. This alone is enough to make one understand how important and fruitful it is to follow step by step the history of political parties, state institutions, etc., in relation to the cycles of capitalist development. By this we do not at all mean to say that these cycles explain everything: this is excluded, if only for the reason that cycles themselves are not fundamental but derivative economic phenomena. They unfold on the basis of the development of productive forces through the medium of market relations. But cycles explain a great deal, forming as they do through automatic pulsation an indispensable dialectical spring in the mechanism of capitalist society. The breaking points of the trade-industrial conjuncture bring us into a greater proximity with the critical knots in the web of the development of political tendencies, legislation, and all forms of ideology.

We observe in history that homogeneous cycles are grouped in a series. Entire epochs of capitalist development exist when a number of cycles are characterized by sharply delineated booms and weak, short-lived crises. As a result we have a sharply rising movement of the basic curve of capitalist development. There are epochs of stagnation when this curve, while passing through partial cyclical oscillations, remains on approximately the same level for decades. And finally, during certain historical periods the basic curve, while passing as always through cyclical oscillations, dips downward as a whole, signaling the decline of productive forces. …

At the risk of incurring the theoretical ire of opponents of “economism” (and partly with the intention of provoking their indignation) we present here a schematic chart which depicts arbitrarily a curve of capitalist development for a period of ninety years along the above-mentioned lines. The general direction of the basic curve is determined by the character of the partial conjunctural curves of which it is composed. In our schema three periods are sharply demarcated: twenty years of very gradual capitalist development (segment A-B); forty years of energetic upswing (segment B-C); and thirty years of protracted crisis and decline (segment C-D). If we introduce into this diagram the most important historical events for the corresponding period, then the pictorial juxtaposition of major political events with the variations of the curve is alone sufficient to provide the idea of the invaluable starting points for historical materialist investigations. The parallelism of political events and economic changes is of course very relative. As a general rule, the “superstructure” registers and rejects new formations in the economic sphere only after considerable delay. But this law must be laid bare through a concrete investigation of those complex interrelationships of which we here present a pictorial hint.

Related articles:

Rulers fiddle with monetary policy, as jobs crisis persists

Front page (for this issue) |

Home |

Text-version home