Vol. 78/No. 4 February 3, 2014

|

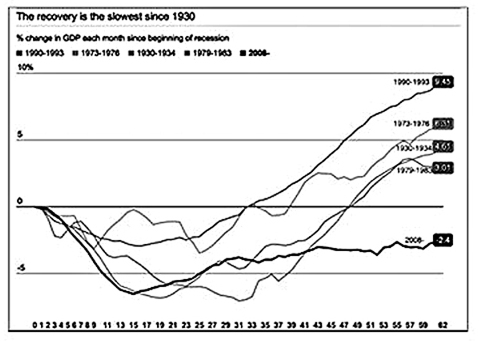

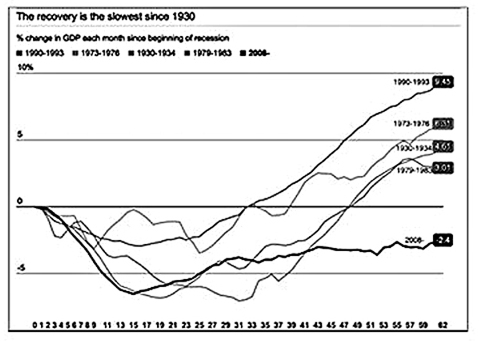

| More than five years after 2008 recession, gross domestic product in U.K. has still not reached pre-recession levels. Chart compares this (dark line) with 62-month period following four previous recessions where GDP reached pre-recession levels within three to four years. |

A week later Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne announced that a £25 billion ($41 billion) cut in government spending would be needed by 2017-18, including £12 billion ($20 billion) from welfare payments.

Unemployment remains higher than it was before the 2008 financial crisis. Real wages have declined. And five years later, gross domestic product remains 2.5 percent below pre-recession levels.

In June 2013 factory output was 10 percent below 2007. This is the slowest economic recovery following a recession since the 1930s.

Talk of “recovery” is based on what appears to be nothing more than an uptick in the business cycle that includes some increased employment. Official unemployment is down to 7.1 percent, the lowest level since 2009. Some 30 million people are working in the U.K. today. But of these, nearly 8 million are working temporary or part-time jobs, including nearly 1.5 million doing so because they cannot get full-time work.

“Slight falls in headline unemployment levels are hiding the fact that more and more workers are taking part-time or temporary contracts because they can’t get anything else,” commented Jacob Mohun of the New Economics Foundation.

Close to 1 million agency workers are on “zero-hour” contracts with no guaranteed hours.

“I do engineering repair work and they want you to be on call all the time,” Carl Towland, from Baguley in Manchester, told the Militant. “Yet some weeks you can get as little as seven hours’ work.”

Real unemployment is closer to 5 million, nearly double the official rate, according to figures released by the Trades Union Congress last September. More than 2.2 million jobless workers want employment but are not counted in official jobless figures. Total unemployment is nearly 1 million higher than in 2008, the union body reports. “Unemployment may have started to fall in recent months,” commented TUC General Secretary Frances O’Grady, “but we are still in the midst of a job crisis.”

Real wages decline

Government figures released last year show that real wages have fallen by an average of 3 percent annually since 2009. One-third of employed workers have experienced wage freezes or reductions between 2010 and 2011, according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies, and 70 percent have been hit with real wage cuts.At the same time, trade union membership in the four years following the 2008 crash declined annually by 100,000. For the last couple years, unionization levels have been roughly 26 percent, down from 32 percent in 1995.

In describing the uptick, capitalist economic commentators have pointed to increased consumption, fueled in part by a rise in housing prices pumped up by the government’s “Help to Buy” mortgage assistance scheme. Other personal debt has also grown, and now stands at a record £1.43 trillion ($2.3 trillion).

A growing number of ruling-class figures and economists are voicing concern that historically low interest rates and other government measures are helping inflate a new financial bubble that could lead to another crash.

Another problem they point to is the fact that Britain continues to import substantially more than it exports, despite a fall in the relative value of the country’s currency, which should make its goods cheaper and therefore more competitive on the world market. The trade deficit remains at 4.4 percent of GDP, the highest of the G7 countries, which include Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, U.K. and U.S.

“Were domestic consumption to slow down, it is doubtful that foreign demand would come to the rescue,” stated a Jan. 14 Financial Times editorial. “In spite of sterling’s steep depreciation, Britain continues to run a large current account deficit. This is unlikely to narrow in the near-term, given the prolonged economic uncertainty in the eurozone — the UK’s foremost commercial partner.”

At the heart of the crisis, however, is a slowdown in production and trade on a world scale. Total output in Europe, Britain’s main trading partner, is down 10 percent from 2008.

What capitalists term “productivity” — measured by the value of output per worker over a given time — has declined in the U.K. since 2008 and lags behind those of its G7 rivals by some 16 percent. Bank lending to businesses has dropped every year since 2008 because many companies see no way to increase profits through expanded production or because banks consider loans too risky.

If the prospects for a real recovery of capitalism are bleak around the world, they’re especially so for the United Kingdom.

Related articles:

Profits before life and limb: two killed in Omaha plant

Port workers in Chile strike for rights of day laborers, back pay

California hospital nurses protest layoffs, outsourcing

Puerto Rico teachers strike over pension cuts

UK gov’t cuts back military

Front page (for this issue) |

Home |

Text-version home