Trying to find out more about the photo on the cover of Pathfinder’s new edition of Che Guevara on Economics and Politics in the Transition to Socialism by Carlos Tablada, I and other socialist workers from Australia, Canada, United Kingdom and the United States participating in the Havana International Book Fair in February learned more about the transformations carried out by working people in Cuba through their socialist revolution. And the central role played in them by Fidel Castro and the rest of its Marxist leadership.

The photo was taken in January 1961 when revolutionary leader Ernesto Che Guevara visited the formerly U.S.-owned nickel mining processing operations in Nicaro, in eastern Cuba, that had recently been nationalized. Guevara was at the time head of the Industrialization Department of the National Institute of Agrarian Reform (INRA), among other leadership responsibilities.

The INRA was created in June 1959 to implement Cuba’s first agrarian reform. Large plantations owned by U.S. and Cuban capitalists were nationalized and turned over to thousands of landless peasants and their families. INRA’s industrialization department was charged with coordinating production in the plants, mines and mills as workers in their tens of thousands were taking control over them.

We spoke with leaders of the National Energy and Mine Workers Union (SNTEM), and Association of Sugar Technicians of Cuba (ATAC), about the photo. They shared with us examples of the accomplishments made by workers in these industries in the opening years of the revolution, gains they continue to defend today.

“If there is a place where these achievements are very palpable it is in Moa,” said Alfredo García, a member of SNTEM’s national leadership. “Moa is the municipality with the second highest level of schooling in the country.” He described Moa’s economic, social and cultural transformation following the revolution’s triumph in 1959 that changed it from a small saw mill and fishing town, dominated by a couple of stores, bars and brothels, to a city with its own university, airport, large hotel and hundreds of multifamily dwellings with access to free health and educational services.

Before the revolution, Nicaro and Moa, located some 50 miles apart, were the site of U.S. mining operations that enjoyed juicy concessions from the Fulgencio Batista dictatorship and its predecessors.

“It used to take four hours to travel the 36 miles between Moa and the closest town, Baracoa, because there was no bridge over the river or any good roads,” García said.

As the new revolutionary government moved to fulfill its pledge to put Cuba’s resources in the hands of working people, the U.S.-run mining monopoly decided to close down the Moa operations in April 1960. They did so in the face of 25% royalties imposed by the new government.

The U.S. mine bosses were used to tax exemptions and other privileges under Batista, because they were contributing “to hemisphere and free world defense.” This was a cynical reference to their products going to supply Washington’s war production during World War II and its 1950-53 intervention against the Korean people.

“Cubans will never be able to start and run the Moa plant,” the U.S. bosses insisted as they left, García said. They left behind new technology they had just installed. The bosses hoped to return triumphantly in a few months, once the new popular government had been removed by pressure, cooption or military intervention by Washington. But those efforts were a total failure.

Victory vs. illiteracy, U.S. invasion

Following the nationalization of the Moa plant in July 1960, Guevara enlisted Demetrio Presilla, one of the plant’s original engineers, to restart production. The Moa Bay Mining Company bosses had urged their engineers to join them in leaving. “They even took the plans and operation manuals,” said García. Only two of the 10 engineers stayed in Cuba.

García said Che convinced Presilla and 17 other technicians to stay. “If you want to leave the country and use your skills somewhere else, fine,” Che said, but otherwise you can stay and build a new Cuba.

On July 23, 1961, the Moa plant was running again, now named Pedro Sotto Alba, after a Rebel Army combatant who fell in 1958 fighting to take the town during the revolutionary war.

Three months earlier, Cuba’s workers and farmers had crushed the U.S.-organized mercenary invasion at Playa Girón (Bay of Pigs). “Getting the Moa plant started became Girón’s technological victory,” said García.

Workers all across the island learned to run the nationalized factories. This required a battle to raise the skill levels of a workforce that first had to learn to read and write.

In 1961 Fidel led working people in Cuba to carry out a massive campaign that wiped out illiteracy in city and countryside. That effort not only dignified generations of Cubans, it helped prepare them for the new tasks they were shouldering in Cuba’s socialist revolution.

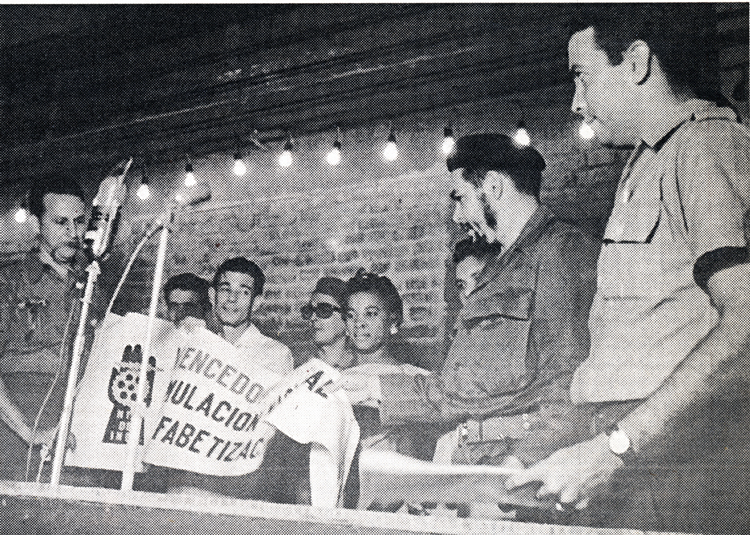

“We’re not trying to set a world record,” Guevara told a November 1961 ceremony held to present a “Territory Free of Illiteracy” banner to workers at a paint factory. “We’re teaching people to read and write so you can learn other things, and combine study and work.” A photo of that event is included in Pathfinder’s new edition of Tablada’s book.

“Building socialism is based on the capacity of the masses to organize themselves, to guide the economy, to improve their knowledge every day,” explained Guevara. The methods used by Guevara, Fidel Castro and other central leaders of the revolution were aimed at raising the self-confidence and political consciousness of workers and rural producers.

Humanizing work

Guevara was also centrally involved in the mechanization of sugarcane harvesting. Under his direction, Cuban engineers and mechanics in the sugar mills built mechanical cane cutters and lifters for loading piles of cut cane onto trucks, based on technology from other countries.

“Fidel’s view was that this work needed to be humanized,” Miguel Toledo, ATAC’s vice president, told us in February. “Fidel wanted to get rid of that symbol of slavery stamped into cane cutters.”

Instead of intensifying their exploitation for cutters, as happens to workers when capitalists introduce new technology, in Cuba their workload was eased and their pay improved.

A lot of political work by the unions went into this transformation, to reassure workers the new measures would benefit them. They guaranteed workers year-round jobs, better housing and nutrition, Eduardo Lamadrid, ATAC’s president, said. Workers in the sugar industry now earned 15% more than workers in other industries. “That’s because it was hard work.”

“The production goals as well as conditions, from wages to food for the workers, were discussed in giant workers assemblies at the beginning of each harvest,” said Lamadrid. “These were very militant meetings in which commander Fidel would participate.”

This revolutionary transformation of working people in Cuba — tied to their fight to wipe out racial discrimination, draw women into the workforce on a large scale, and support workers’ struggles internationally — is why the capitalist rulers in Washington hate Cuba. Their revolution is an example for workers worldwide.