lead article

Bush tour of Europe seeks to assert U.S. domination

Washington presses Moscow to accept NATO expansion

BY GREG MCCARTAN

In a five-nation trip to Europe in mid-June, U.S. president George Bush advanced the military and political objectives of the U.S. ruling class vis-à-vis Russia and Washington's imperialist allies in Europe.

Bush used the trip to take a new step in the drive by Washington to expand eastward the U.S.-dominated NATO military alliance, assert its determination to move ahead with an antimissile weapons system, and press the Russian government to accept these moves in exchange for "integration" into Europe. He said the European Union (EU) would have to bear both the "burden" and "benefits" of carrying out this course.

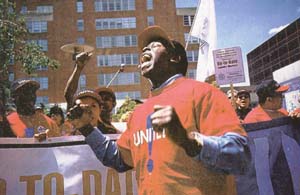

Laundry workers in Baltimore win UNITE union contract

Picket line at Up-To-Date Laundry in Baltimore in June. The workers won their fight to be organized by the Union of Needletrades, Industrial and Textile Employees (UNITE) and gained a contract after a nine-week strike. They won broad support from other workers both in Baltimore and other parts of the country. "We achieved our objectives: a union contract, respect, health care, a pension fund, and some more money," said unionist Jaime López. See article on page 3.

Picket line at Up-To-Date Laundry in Baltimore in June. The workers won their fight to be organized by the Union of Needletrades, Industrial and Textile Employees (UNITE) and gained a contract after a nine-week strike. They won broad support from other workers both in Baltimore and other parts of the country. "We achieved our objectives: a union contract, respect, health care, a pension fund, and some more money," said unionist Jaime López. See article on page 3.

|

Bush met with top government officials during stopovers in Spain, Belgium, Sweden, Poland, and Slovenia, where he held a two-hour "summit" with Russian president Vladimir Putin. In Brussels he met with leaders of NATO powers, and in Goteburg, Sweden, with heads of state of EU nations.

In a June 15 address at the University of Warsaw, Bush argued for putting NATO expansion on the fast track. "I believe in NATO membership for all of Europe's democracies that seek it and are ready to share the responsibilities that NATO brings. The question of 'when' may still be up for debate; the question of 'whether' should not be."

One of the main axes of Washington's drive to expand NATO and deploy an antimissile shield was to hold out an offer to the Russian government that it can come under the protection of a U.S.-dominated military alliance in Europe and receive economic aid from those countries. This would mean the European Union governments underwriting massive support payments and capital transfers to workers states in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union, countries where capitalism has been overthrown.

"Across the region, nations are yearning to be a part of Europe," Bush said in his Warsaw speech, referring to the desires of the pro-capitalist ruling layers in Eastern Europe and countries of the former USSR. "The burdens--and benefits--of satisfying that yearning will naturally fall most heavily on Europe itself." He presented a view of an imperialist-led European bloc, including countries from the "Baltic to the Black Sea and all that lie in between." Among those countries he included the "Ukraine, a nation struggling with the trauma of transition," a euphemism for the fact that capitalism is far from being reimposed in that workers state.

The U.S. president said Europe must "be open to Russia. We have a stake in Russia's success--and we look forward for the day when Russia is fully reformed, fully democratic, and closely bound to the rest of Europe. Europe's great institutions--NATO and the European Union--can and should build partnerships with Russia and all countries that have emerged from the wreckage of the former Soviet Union." He added that "Russia is part of Europe and, therefore, does not need a buffer zone of insecure states separating it from Europe."

The Financial Times of London noted the pro-Washington "yearnings" of a senior Czech diplomat prior to Bush's visit who summed it up this way: "By NATO we mean the U.S. The EU is about economic integration. But we are Atlanticists. We see the US/NATO security role complementing the EU's economic role. They go hand in hand. This is the message we want to hear from Bush. This is why enlargement must continue."

NATO admitted Poland, the Czech Republic, and Hungary in 1999, extending the imperialist military alliance right up to the borders of Russia.

Antimissile weapons and ABM treaty

In declaring its intention to deploy sea-, land-, and space-based missile intercept weapons as part of a "National Missile Defense," which was previously a priority of the Clinton administration, Washington has openly declared the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty a thing of the past. In addition, Bush has stated his intention to drastically cut the number of nuclear warheads in the U.S arsenal to around 2,000 or less.

The Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty stipulates that Washington and Moscow will not "develop, test, or deploy ABM systems or components which are sea-based, air-based, space-based, or mobile land-based." It does not rule out fixed land-based missile systems or those for small geographic areas, known as "theater" missile defense.

The U.S. Navy has been developing ship-based interceptors and the Air Force is testing lasers mounted on an airplane. Both could be used in the broader system envisioned by the U.S. rulers. "We do all our testing in accordance with the treaty," claimed Lt. Gen. Ronald Kadish in congressional testimony recently. "And it hasn't prevented us from doing what we need to do for the ground-based system per se."

Philip Coyle, former head of weapons testing at the Pentagon, said that the 1972 treaty has not held Washington back from "development of the technology needed for national missile defense, nor is the treaty slowing the testing of an NMD system."

Both statements, in addition to the Bush administration's stated goal of cutting Washington's massive nuclear arsenal, point out the degree to which the ABM treaty is already a dead letter, something Bush used to his advantage to counter protests by the French and German governments over the scrapping of the treaty.

Russian president's response

After his meeting with Bush, Putin said he was "very grateful" that "these words" about Russia's integration into Europe and relations with NATO were "finally" heard from the president of the United States. "This is very important for us. We value this. When a president of a great power says that he wants to see Russia as a partner, and maybe even as an ally, this is worth so much to us," he declared.

Putin responded to Bush's statements by urging Washington not to act "unilaterally" on the missile shield plan. "The president now says that Russia and the United States are no longer adversaries; moreover, they can become partners," he said. "It is precisely from this standpoint that we should have a look at the entire package of previously concluded agreements between us."

Putin said he "offered to work together" with Bush on the missile defense, but that if Washington moved ahead without Russia, "we are ready to act on our own." The Russian president asserted that Moscow would deploy multiple nuclear warheads atop the country's current single-warhead missiles in order to potentially overwhelm any U.S. defense system. But he put off the possibility of doing this for a long time, stating that he was "confident that at least for the coming 25 years" the missile system "will not cause any substantial damage to the national security of Russia." Shooting down a missile is "like a bullet hitting a bullet," the Russian president said. "Is it possible today or not?" adding that "today it is impossible."

'Putin's bluff'

In an opinion column entitled "Putin's bluff" that appeared in the June 21 Financial Times, Padma Desai, director of the Center for Transition Economies at Columbia University in New York, said, "The Russian bear is trapped between a failing economy and pressing defense needs on the nonnuclear front."

The Russian president's threat to deploy missiles with multiple warheads if Washington moves ahead unilaterally to deploy an antimissile system is "little more than noise and cheap bargaining. Mr. Bush has the bear over the barrel," Desai wrote. He added that "Russia's dependence on foreign assistance continues to be acute" and that recent budget improvements only reflect "the massive increase in oil revenues because of high oil prices and that is unlikely to last."

While figures for Russian government expenditures vary widely, most sources put the upper limit at around $60 billion. One-quarter of the budget goes to service the country's debt payments to imperialist banks, a figure that is expected to rise to one-third of government expenditures by 2003. The defense budget is estimated by several sources at $5 billion. By contrast, the U.S. government has an annual federal budget of $1.78 trillion, some $300 billion of which is earmarked for military spending. Expenditures for missile systems are expected to increase by $2.2 billion next year.

The extent of the economic difficulties in Russia and the rapid deterioration of the country's economy can be seen in the fact that the most optimistic figures record its gross domestic product (GDP) at $593 billion in 1998, ranking 14th in the world--above south Korea and below Indonesia. With a population of 146 million, Russia's per capita GDP is $4,000, placing it among the lower tier of countries. By contrast, Turkey, a semicolonial country of 65 million, had a per capita GDP of $6,600 in 1998, and the Dominican Republic a per capita GDP of $5,000.

Desai wrote, "There is no doubt that Mr. Putin must dread the prospect of NMD eventually destroying the utility of Russia's nuclear stockpiles and turning the U.S. into a hyper-power with first-strike capability without fear of retaliation.... His budget cannot possibly find the necessary resources to begin a nuclear arms race; and his immediate defense needs are focused on the country's difficult neighbors."

Reactions from Germany, France

NATO members are not unanimous in their support to Washington's plans. French president Jacques Chirac said after the NATO meeting that a missile shield would be a "fantastic incentive to proliferate weapons" for countries that want to try to overwhelm any defense system and added that he saw the need to preserve "strategic balances, of which the ABM treaty is a pillar."

German chancellor Gerhard Schröder said he saw "a host of issues that need to be clarified, and therefore we must and indeed will be continuing intensive discussions on this subject." Newly elected prime minister Silvio Berlusconi of Italy said the differences were a matter of "degree of enthusiasm between those who are more advanced on the project and those who are less advanced."

The U.S. president urged EU members to accelerate their eastward expansion plans, something the Swedish government, which currently holds the presidency of the EU, has placed at the top of its agenda. The meeting in Göteborg agreed to this perspective, despite stated reservations by the German and French governments, setting the end of 2002 as the date by which to complete negotiations with up to a dozen countries on joining the EU. Top on the list are Hungary, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Slovenia, and Poland. Others in discussion with the EU are Cyprus, Bulgaria, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, and Romania.

What bearing the "burden" of the EU expansion means and the impossibility of reimposing capitalism through simply economic means in workers states in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union can be seen in Germany. At the end of June, Germany's federal government decided to extend massive financial subsidies to the region comprising the workers state in eastern Germany--the former German Democratic Republic--until 2020, starting with a $134 billion commitment. Over the first decade since reunification in 1990, the German government transferred $540 billion in direct subsidies to the east. Despite this, the region's unemployment remains at 18 percent, its per capita gross domestic product remains at only two-thirds of that in the west, and a construction and real estate speculation boom has gone bust.

Taking a typically arrogant, American nationalist tone, New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman wrote in a June 22 piece that the EU is "economically strong enough to play an important role in stabilizing messy states in Western Europe, Russia, Central Europe, and even North Africa, by nurturing these regions toward democracy and capitalism. But it is politically divided enough, particularly on foreign policy, not to pose any serious challenge to U.S. global leadership."

In face of the fact that Washington will press ahead regardless of the stand of any individual government, an unnamed diplomat from a major European imperialist power told the Financial Times that the EU powers are "trying to develop our own European Security and Defense policy. But if MD [missile defense] goes ahead, we will be beholden to the Americans for our security." No matter what extent of economic integration is achieved, "being beholden to the Americans" militarily gives Washington a strong leg up in relation to its imperialist allies/competitors in Europe.

Kyoto treaty

Bush also brushed aside criticism of his administration's decision not to sign the 1997 Kyoto Protocol on climate control, exposing the hypocrisy of the big powers in Europe on air pollution controls.

The Kyoto agreements set targets to cut heat-trapping greenhouse gases by 5.2 percent below 1990 levels by 2012. Government representatives from economically advanced countries agreed to slightly more stringent reductions than seimcolonial countries. At the time, both U.S. president Clinton and vice president Albert Gore said they would press, in Gore's words, "for meaningful participation by key developing nations." Bush has continued this theme.

Imperialist powers could easily get around the emission standards, though, through a system of "trades" built into the treaty that allowed a government to "buy" emissions reduction permits from another government. The New York Times wrote at the time that the agreement was held up due to "resistance" by "some of the developing nations, including China, India, and Saudi Arabia, to the inclusion of a provision enabling the industrialized nations to trade or purchase emissions rights," and that the "objectors said that the mechanism could lead to shifting the burden to less developed countries, and that countries and companies might be able to buy their way out of their obligations."

Philip Gordon and James Lindsay of the liberal Brookings Institutions wrote in a June 22 column that Bush had the upper hand in defending Washington's decision. They say that "the four-year-old Kyoto accord has yet to be ratified by a single European country, most of which have made little progress in curbing their own emissions."

|