GREENSBORO, N.C. — The school workers uprising that started in West Virginia in late February and has since rolled across Kentucky, Oklahoma, Arizona and Colorado, has hit North Carolina. More than 11,500 teachers have already filed for personal days to march and rally outside the Capitol in Raleigh at the opening of the state legislative session May 16.

“13 and Counting” is the headline in the May 8 Raleigh News & Observer — adding up the number of school districts that have announced they’ll be closed for the protest. District officials say too many teachers have marked off to keep the schools open.

They are joining the tens of thousands of teachers, other school workers and supporters who have protested wages and working conditions, attacks on pensions, increased health premiums and deteriorating schools.

Guilford County is one of the growing number of counties closing their schools for lack of teachers May 16. “I think it’s a clear indicator that teachers are fed up with a lack of funding, a lack of workplace dignity, a lack of resources,” Todd Warren, a teacher and president of Guilford County Association of Educators, the main teachers union, told the media May 7.

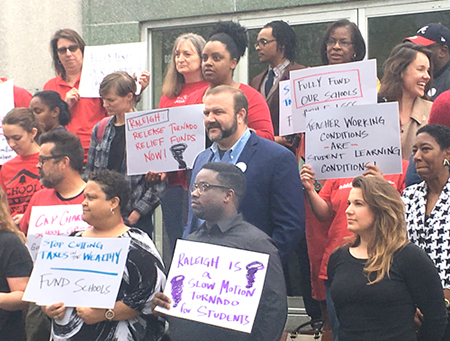

The union presented its demands and publicized the action at a press conference here April 26, attended by teachers, parents and supporters. They also called for relief for schools that were severely damaged, along with many homes, when a tornado ripped through the east side of Greensboro 11 days earlier. They said the damage to the schools could have been prevented if the buildings had been maintained and renovated.

“We celebrated today when Guilford announced it would close,” Susan Skinner, who teaches at Swann Middle School here, told the Militant May 7. She is a member of the union and has been active building the May 16 rally. “We’ve talked about how we need to talk to everybody — teachers, bus drivers, cafeteria workers, custodians, everybody.”

Skinner said that as they’ve been building the actions, workers have gotten more confidence and are beginning to broaden the discussion.

“You know, you’re in your classroom, fairly isolated and have little experience of collective strength,” she said. “Then you see this movement rolling across the country and what it has achieved. Discussions are shifting a bit now to what is most important and what it will actually take to win.”

North Carolina is one of the centers for manufacturing in the U.S., with substantial automotive and aerospace industries, as well as food processing, furniture manufacturing and tobacco. Goodyear and Bridgestone Tire companies, Smithfield Foods, Tyson Farms, Volvo, Caterpillar and dozens more have thousands of workers in the state. Of course Walmart is the largest employer.

Workers have been hit hard. Between 2004 and 2006 almost 39,000 workers lost their jobs as bosses searching for higher profits outsourced the jobs, devastating the state’s textile and furniture industries.

And, unlike some other states where teacher uprisings have broken out, North Carolina has a sizable Black population with a history of battles against racism and police brutality that date back to Radical Reconstruction. In 1960 students sat down at Woolworths in Greensboro, helping launch a wave of sit-ins against Jim Crow segregation across the country.

Today there is an ongoing debate about what to do with still-standing statues of defenders of slavery in the Civil War. These struggles have affected the working class as a whole, including the International Longshoremen’s Association local in Wilmington.

And the legacy and battles around slavery and racism affect the schools. “People talk a lot about the disparity between the conditions in some ‘whiter’ areas, as opposed to the worse conditions in schools that have more Black students,” Skinner said.

While the protest takes place in Raleigh, teachers in Greensboro have organized a food committee to bag lunches and staff distribution points to feed several hundred students.