YABUCOA, Puerto Rico — “We were hit by two hurricanes. One was Maria. The other was the social hurricane. It’s much worse than the natural one, and it’s still with us.”

This is what person after person told us during a fact-finding reporting and solidarity trip to Puerto Rico in late May by the Militant editor and a reporter for the paper, both members of the Socialist Workers Party. We visited towns and rural communities in the southeast as well as the capital, San Juan. What they described is the result of capitalist rule in a nation under the U.S. colonial boot.

More importantly, workers told us the ways they have begun to organize to confront the social catastrophe that unfolded after the storm devastated the island last September. Protests have been organized by people who had never been involved in such activity — demanding the government restore electric service and provide aid, and opposing the closure of public schools.

The big-business media has portrayed working people here as helpless victims. “Yabucoa Lives Amid Resignation and Darkness,” was the front-page headline in the May 28 El Nuevo Día, a major daily.

But the picture we saw was quite different. In face of the collapse of services essential to daily life and the callous indifference to what working people faced from capitalist authorities — from Washington to San Juan — what comes through is resilience and increased confidence, as thousands join together in working-class and rural neighborhoods across the island to fight, rebuild and take care of each other.

And there’s a thirst to know why this happened to them and how they can make sure it never happens again.

“I like the word solidarity, because that’s what we’re doing here,” said Lenis Rodríguez as he took us around his hometown of Yabucoa, on Puerto Rico’s southeast coast. Rodríguez works afternoon shifts at a nearby pharmaceutical plant and spends much of his free time organizing together with other residents to help meet basic needs, both in the city and surrounding rural areas.

In March, after six months without electricity, he and others in the Jardines de Yabucoa neighborhood organized a “march of the flashlights” to protest the government’s inaction. It was covered live by reporter Yeidy Vega, who herself lives in an area of Humacao that still lacks service. She told us, “I try to cover all the demonstrations I can get to.”

“The next day I got a call from engineers at the electric company,” Rodríguez said with a smile. “That’s how our neighborhood got power back. But most of Yabucoa is still without electrical service, and we’re still fighting.”

Today, tens of thousands of people remain without power, especially in Humacao and Yabucoa, where the hurricane made landfall, and in Utuado and other towns in the mountainous interior.

‘A disaster waiting to happen’

“It was just a matter of time before a disaster like this was going to happen,” said Raúl Laboy, a retired electrical worker in the Mariana neighborhood, located in the hills overlooking Humacao. “We’re a U.S. colony, and the priority of the colonial rulers is to enrich U.S. corporations at our expense. We are not the owners of our own country.”

Since Washington invaded and seized Puerto Rico in 1898, U.S. capitalists have warped its economy to serve their profit interests. They have turned the island into an export platform based on superexploited labor, maintaining a large reserve of unemployed workers, keeping wages and living standards much lower than in the United States.

Puerto Rico’s economic decline, which began in the world capitalist depression in the mid-1970s, has taken a nose dive since 2006, as the global crisis further battered the island. To pay the debt owed to U.S. bondholders — now at $74 billion — the colonial government has slashed 30,000 public employee jobs, cut retirement pensions, hiked sales taxes, closed more than 100 schools and put 266 more on the chopping block, and changed laws to make it easier for bosses to fire workers at will.

U.S. junta: more attacks on workers

“Today the U.S. capitalists are imposing their decisions even more directly on us,” said Angel Figueroa Jaramillo, president of UTIER, the electrical workers union. “We’re fighting the fiscal control board, which now makes the economic decisions in Puerto Rico. To pay the bondholders, they want to carry out even more drastic cuts in social benefits and eliminate rights workers have won.” The board, or junta, as it’s commonly known here, was appointed by President Barack Obama in 2016.

Speaking with us at the UTIER hall in San Juan, Figueroa and union Vice President Freddyson Martínez said the junta and colonial authorities are stepping up pressure to sell off the state-run Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority to private owners. They are seizing on widespread resentment of government mismanagement of the utility, which accounts for $9 billion of the total debt.

“It’s not a surprise the electrical grid collapsed,” Figueroa said. “Our union had been warning for a long time that more blackouts were bound to happen because of decades of lack of maintenance and reductions in personnel. They let the whole system go downhill.”

“The power authority had reduced inventories to a bare minimum and sold off equipment in order to make debt payments,” Figueroa said. After the storm, they were short of electric poles, cables and other equipment, sharply slowing the process of restoring power.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the electrical company awarded billion-dollar contracts to Cobra Energy and other U.S. contractors to import supplies and deploy line crews. In mid-May, however, the Army Corps suddenly announced it would withdraw its 700 line workers from Puerto Rico, claiming their work was done. That outraged many workers we met in Humacao and Yabucoa, who still had no power.

The social catastrophe and anti-labor attacks have generated mounting anger among working people. Both of the ruling colonial parties responsible for these attacks are deeply discredited.

“We saw the mood of the working class in the May Day marches both this year and last. They were much bigger than in past years, with tens of thousands of marchers,” said José Rodríguez, a union representative for the Solidarity Union Movement (MSS). The union represents workers at a Pepsi bottling plant. Fernando Santiago, a Pepsi delivery truck driver and MSS president, told us the union is involved in an effort to organize 1,800 Coca-Cola distribution workers.

The May Day marches also drew university students, who are also feeling the ax. Gabriel Díaz, one of the University of Puerto Rico students who helped lead last year’s student strike, reported that, at the behest of the fiscal board, university tuition will double in August.

“If you’re taking 15 credits, your tuition will jump from $850 to more than $1,700 per semester,” he said. “And they’re closing down some student housing that working-class youth from out of town rely on,” said Verónica Figueroa, another University of Puerto Rico student. Díaz and Figueroa are among seven youths who face felony and other charges filed against them by U.S. authorities because of their role in the student protests.

In Humacao: ‘We helped each other’

Our two-day visit to the island’s southeast corner was especially striking, both by how naked the face of the capitalist crisis has become to millions and by working people’s response to it — the resistance, solidarity and creativity.

Hurricane Maria devastated Humacao, a municipality of 52,000 that encompasses the main town and rural communities. When we arrived May 26, thousands of residents and small businesses were still without electricity. Many homes had blue tarps where the roofs had been ripped off, the owners still waiting for aid to rebuild.

We were invited by local residents to visit the neighborhood of Mariana, reachable by narrow roads that wind up and up the hills.

“For the first week after the hurricane, not a single government official showed up here,” Mariana resident Ivette Díaz told us. Her house was damaged when a neighbor’s home was torn off its foundation and slammed into hers.

“We got no help from the government,” she said. “So neighbors just got together and started to clean up everything.” They cleared debris to reopen the roads. They cleaned up their homes and those of their neighbors.

By the second week some federal agencies showed up, offering each home a few bottles of water.

“The mayor of Humacao came to Mariana a month later. The governor of Puerto Rico arrived in town to inaugurate the Walmart when it reopened, but he’s never come here,” Díaz said.

Her phone service was finally restored in January. She now has electricity; many others in Mariana don’t. “After the storm, if you tried to buy a generator, it could cost $1,000 to $2,000,” she said. “The diesel fuel costs $15 to $20 a day. It’s just too expensive.”

The leaders of ARECMA, the Recreational and Educational Community Association of Mariana Neighborhood, had offered to take us around the area. We followed Rosalina Abreu, the group’s president, by car to the top of the hill, which offers stunning views of the lush countryside below. She proudly showed us their facilities. One wall is decorated with a mural depicting Julia de Burgos, one of Puerto Rico’s foremost poets, that was painted by New York artist Molly Crabapple last October.

Abreu and Mildred Laboy, another leader of ARECMA, told us a little about the organization’s work in Mariana, a neighborhood with 3,200 residents. “Everything this community has was won through years of struggle, not handouts,” Abreu said. ARECMA was founded in 1982 but community struggles go back to the 1960s, as they successfully battled to get the government to provide drinking water, electrification and paved roads.

“After the hurricane everything collapsed,” said Laboy, who like Abreu is a retired schoolteacher. “For months, like much of the country, we had no electricity, water, communications, or medical services. And no jobs.

“Because of our past experience, we weren’t surprised that we got no help from the government. We were ready and began to organize ourselves.” People pushed aside debris to look for their neighbors. They patched up damaged roofs and broken windows.

Abreu proudly showed us the community kitchen they set up, where volunteers serve meals every weekday to people who have no power to cook. At the high point they provided 500 lunches a day. They appealed for and received donations from Puerto Rican communities in the United States.

They showed us the eating area and the water-filtration equipment they set up to provide drinking water. They have raised money for solar panels to run the kitchen and become a little more self-reliant, while fighting for the government to restore service to all. They built recreational facilities with musical and other cultural activities for the children.

Laboy pointed to the class bias of the government’s priorities in Humacao. They first made sure to restore power for the luxury villas in the Palmas del Mar resort and the Ex-Lax and other U.S. pharmaceutical plants in the area.

Protests across island demand power

Abreu said there have been numerous demonstrations in Humacao demanding restoration of electrical service. “There was a torchlight march, and a march on the bridge between Humacao and Las Piedras,” she said. “Some people went to San Juan to demonstrate in front of government offices.”

Similar actions took place across the island. In just one week in December, the press reported 17 marches, picket lines, road blockades and other actions, from San Juan to Isabela in the west, Salinas in the south, and Caguas in the center of the island.

“Just in Mariana they closed four schools, and we have one elementary school left. Now some kids have to travel 5 kilometers [3 miles] to and from school. Transportation is more difficult in rural areas,” Abreu said.

Laboy took us to another part of Mariana where her brother Raúl “Ruly” Laboy was helping rebuild another brother’s house whose roof was ripped off and windows shattered by the storm.

The retired electrician explained that many who applied to the Federal Emergency Management Agency for aid to rebuild their homes have been turned down. The U.S. agency demands property deeds and other documents that many in rural areas don’t have. “If you don’t have a deed you have to hire a land surveyor and go to court. It can take 10 years and a lot of money to get legal documents to prove you own a house that belonged to your grandfather,” he said.

Despite the challenges, said Raúl Laboy, “I’m not going anywhere. I’m staying right here. We rely on working-class solidarity and that makes me happy.”

He was excited to meet two members of the Socialist Workers Party from the U.S. Like many others we met, he subscribed to the Militant and purchased some books we brought by SWP leaders on revolutionary politics.

While Raúl Laboy is a veteran socialist, a supporter of revolutionary Cuba and an advocate of independence for Puerto Rico, we got a similar response from other workers who didn’t have a political background. They were interested to hear about the recent wave of teachers strikes across the U.S. They were open and in many cases attracted to the revolutionary working-class perspective we discussed with them. Is Socialist Revolution in the US Possible? was the most popular book we showed people.

Struggles in Yabucoa

The next day we went to the coastal town of Yabucoa, 20 minutes south of Humacao. You can see the island of Vieques — for decades a target of U.S. Navy practice bombings and of protests by residents that finally stopped them. It’s where Hurricane Maria made direct landfall and where some 60 percent of homes still had no electricity when we were there. Lenis Rodríguez organized a full day of visits for us in different rural neighborhoods.

Rodríguez has been a leader of Yabucoa Support Group, a community organization, for the past 13 years. After the storm hit, he and others in the group went into action to recruit volunteers to help bring food and supplies to neighbors and residents of other communities. In March he organized the “march of the flashlights,” which inspired similar protests in Humacao and other areas demanding the government restore power.

“You can see a class bias here,” Rodríguez said. “People in these areas don’t get attention that other classes get.”

In the neighborhood of Tejas, in the hills above the main town, we were invited into the home of Annette Aponte, a teacher. We also met her brother Bedwin, a manufacturing worker, and her elderly parents, Mario Aponte and Justa Serrano. They were eager to talk to Militant reporters “so people in the United States can hear what we’re going through,” Annette said.

Mario is a living history of the Puerto Rican working class. Today he is in frail health, but he came alive telling us how as a teenager in the early 1960s he had cut sugarcane with a machete when the big Roig sugar mill in Yabucoa was still running. Then, like tens of thousands of Puerto Ricans in the 1950s, he migrated to the United States and got jobs as a farmworker in New Jersey. He also worked at the Union Carbide electrode plant in Yabucoa that later closed.

Serrano described what happened last Sept. 20 when the hurricane barreled into Yabucoa. Their front gate and windows were blown out and the house, which sits on a hill, was shaking. Shortly after the storm, the containment wall behind the house broke and slid down the hill. They were afraid the house would follow it.

“Two or three days later, when the road was reopened, we were able to go down to the town and ask for a tarp to reinforce the ground behind the house. But the mayor’s office refused us any help,” Annette Aponte said. Finally a pastor gave them a tarp.

She was out of work and without income for three months after the storm. “We went to FEMA to ask for financial help to rebuild the containment wall,” she said. “They turned us down twice but we kept appealing. The third FEMA inspector asked for documents, then more documents, to certify that it was my father’s house. We gave them the papers. We’re still waiting for FEMA to reply.”

The Tejas neighborhood was still without power when we visited. “My father has diabetes and we need ice to keep his insulin supply refrigerated,” she said.

“But the mayor of Yabucoa hasn’t even bothered to come up here, and he’s been slow in responding to our needs,” Aponte said. She told us she thinks part of the reason is that he represents the Popular Democratic Party while most Tejas residents voted for the rival, pro-statehood party. Patronage politics by both colonial parties has a long history in Puerto Rico.

Actions against school closures

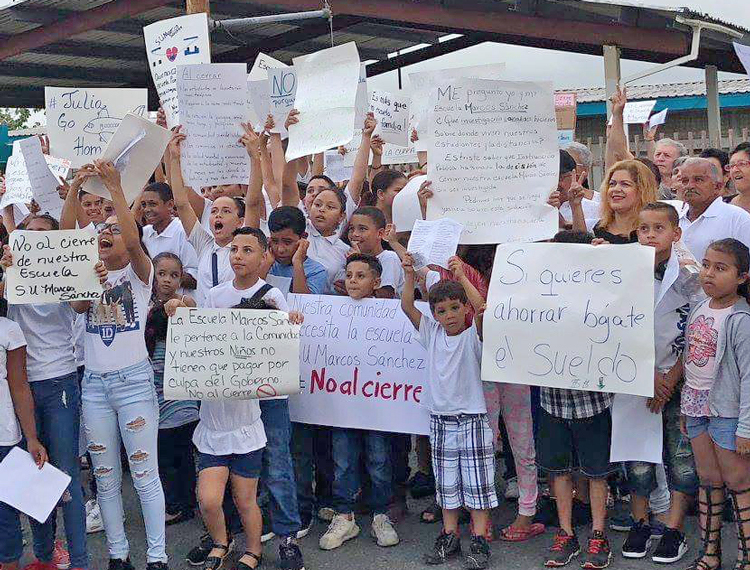

Aponte said that the government in Yabucoa had announced that five schools would be closed. “Parents and students went into the streets to protest, and they were able to save two of the schools.”

As she waved goodbye to us from her front entrance, next to her was a large Puerto Rican flag hanging on the outside wall. Since the storm working people across the island have displayed the flag on their homes and cars. It means: “We survived, we’re determined to rebuild, we’re staying here in our country.”

Next we visited Orlando and Aida Ramos in the neighborhood of Ingenio, which is “sugar mill” in Spanish. Born in the Bronx and moving here as a child, Orlando worked in the mid-1970s at the nearby Roig sugar mill; earlier we had stopped to see the long-abandoned buildings that sit today as giant rusting hulks. He later worked hanging chickens in poultry plants. Aida worked in poultry plants in Massachusetts and garment shops in Puerto R

Aida Ramos reported that just two days earlier the first repair crews from Cobra had arrived in the neighborhood, installing electric poles. We saw them driving around. But eight months without power has taken a toll on working people here.

“A neighbor who was in ill health died yesterday,” Orlando said. “Not having electricity has an impact. It means no air conditioning. Food spoils and ice melts. It means no oxygen machines. And no TV to relieve the mental stress everyone has been going through.”

Several other workers told us of relatives or neighbors who had died over the past months as a result of similar conditions, either at home or at medical facilities crippled by the storm.

Like others we spoke with, Orlando appreciated the discussion about the capitalist crisis we face both in Puerto Rico and the U.S., and how workers can unite to fight more effectively today. He said he looked forward to us coming back. “Let me know when and I’ll fire up the barbecue,” he said.

Fishermen’s struggles

Lenis Rodríguez introduced us to Luis “Cheverito” Velázquez, a local fisherman. Velázquez told us that fishermen, who are organized into associations in many coastal towns, have had to fight for basic things like getting the local government to build a small dock.

Hurricane Maria destroyed the little dock — along with fishing traps and other equipment — and now Velázquez and others have to launch their boats from the beach. A fellow fisherman who has electricity makes his refrigerator available so they can store their catch.

Cheverito, as everyone calls him, goes fishing on his 16-foot boat with two other crew members at least once a week. He also works full time as a janitor at the school in Punta Santiago and is active in the union. “It’s a poor neighborhood where most of the kids come from families of fishermen,” he said.

After the hurricane wiped out the school, Cheverito and other janitors, joined by parents and volunteers, worked overtime to clean it up, turning it into a place people could gather in and use.

Velázquez sometimes fishes off nearby Vieques. “The water is still contaminated with shells and other waste left from when the U.S. Navy used Vieques for target practice until we forced them to stop,” he said.

He’s a veteran of those battles, pioneered by fishermen, that eventually led the U.S. military to leave Vieques in 2003. “It was truly David and Goliath — the fishermen with their little boats and their slingshots standing up to the Navy with their giant ships and resources,” he said. “And we won.”

He says when we come back he’ll take us to meet fishermen in Vieques.

Rebuilding after the storm is one more battle. “I’ve been fighting all my life, Cheverito said. “And today I’m still fighting. I’m staying here.”