NEW YORK — For weeks mass protests have shaken Algeria, forcing the resignation of longtime president Abdelaziz Bouteflika April 2. Tens of thousands have continued to take to the streets rejecting the new interim president and other figures associated with the regime.

These developments and the background to them were the topic of a Militant Labor Forum held here April 13. The speaker was Martín Koppel, a member of the Socialist Workers Party in New York.

Koppel described the depth of the popular struggle in Algeria, led by the National Liberation Front (FLN), that defeated French colonial rule in 1962. In Algeria, unlike other independence struggles in the region, the deepening of the revolution led to the establishment of a workers and farmers government — “a government independent of the capitalist class,” he noted.

From the beginning, the Socialist Workers Party and its co-thinkers internationally embraced the Algerian Revolution as their own, Koppel said. They promoted international working-class solidarity through the Militant and other publications such as World Outlook, edited by SWP leader Joseph Hansen. Algeria’s workers and farmers government, as well as its overthrow in 1965, have important lessons for working people everywhere.

Workers and farmers government

The revolutionary government, whose central leader was Ahmed Ben Bella, mobilized hundreds of thousands of working people and began to encroach on the prerogatives of the capitalists and landlords, both foreign and domestic, Koppel said.

Peasants mobilized to back a deepgoing land reform in which the most productive capitalist landholdings were nationalized. Several hundred enterprises were nationalized, although not the oil industry, banks, or other key sections of the economy.

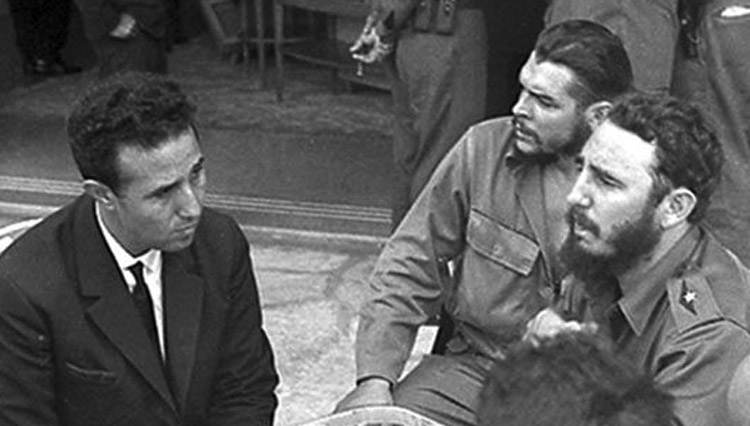

The Ben Bella leadership collaborated with Ernesto Che Guevara and other Cuban revolutionary leaders in supporting anti-imperialist struggles throughout Africa and elsewhere.

But the revolutionary leadership began to hesitate and make unnecessary concessions to procapitalist forces. When a second, deeper stage of the land reform was postponed, this discouraged and demobilized peasants.

“The biggest single challenge in the Algerian Revolution was the lack of a working-class party with a communist leadership,” Koppel said. Such a leadership was needed for workers and peasants in Algeria, in face of opposition by the capitalists and landlords, to overturn capitalist property relations and establish a workers state. That was the lesson of the successful socialist revolutions in Russia in 1917 and Cuba in 1959.

“One thing that politically weakened the revolution,” he noted, “was the 1963 law that effectively excluded non-Muslims from Algerian citizenship,” including 1.4 million Algerian-born French, known as Pieds-Noirs, as well as 130,000 Algerian Jews. Although a majority of these layers had opposed the independence struggle, the FLN leadership “missed the opportunity to win over as many as possible” to contribute to the building of a new Algeria. This was not a small question given that, after a century of colonial underdevelopment, Algeria faced a shortage of skilled technical personnel.

The exclusion of non-Muslims was an obstacle to the development of class consciousness and the barring of citizenship for Jews reinforced anti-Semitic prejudice.

Koppel noted that Algeria’s citizenship restrictions were even more drastic than those adopted in Israel after its establishment in 1948. There, he said, citizenship was granted to all Jews based on descent and to a substantial minority of Arabs based on residence — which was bitterly opposed by the right-wing Zionist faction of the Israeli leadership, who thought they were “giving the farm away” by allowing Arab citizenship at all.

Koppel told the forum that in 1963 Cuban revolutionary leader Fidel Castro had planned to visit Algeria. But after the Cuban government, which maintained diplomatic relations with Israel, declared three days of mourning following the death of Israeli President Itzhak Ben Zvi, Bella publicly declared, “Whoever respects a dead Israeli in that way has no right to come to an Arab land.” The Cuban leader canceled his visit.

In June 1965 the workers and farmers government was overthrown in a coup led by Col. Houari Boumediene, backed by then-Foreign Minister Bouteflika.

Need for communist leadership today

Koppel noted the mass protests unfolding across the region today, from Sudan to Mali, in response to conditions bred by the world capitalist economic crisis. In face of this crisis “all these regimes have historically exhausted their capacity to provide any semblance of progress,” he said.

This is explained in an article in issue no. 12 of the Marxist magazine New International, Koppel said. It points to “the exhaustion of the bourgeois-nationalist leaderships that, over the span of some eighty years, came to power on the shoulders of anti-imperialist struggles involving hundreds of millions of workers, peasants, and youth across Asia, Africa, and the Americas.”

“That’s what we saw with the Arab Spring” in 2011, Koppel said, where revolts took place “against regimes that claimed to represent the interests of the majority against imperialism but were responsible for increasingly intolerable conditions.

“Turmoil and war will continue, including in countries where jihadist forces have filled the vacuum,” until a proletarian leadership can be forged through the struggles and experiences of working people, he said.

Malcolm X and SWP

Koppel also focused on the impact the Algerian Revolution had on revolutionary-minded working people and youth worldwide, including those joining the Socialist Workers Party at that time. It had a particular impact on revolutionary leader Malcolm X, who often referred to the Algerian and Cuban revolutions as examples of what needed to be done here.

Malcolm explained how his thinking was changed by his exchanges with revolutionary leaders in Africa in a 1965 Young Socialist interview with Jack Barnes, now SWP national secretary. It’s reprinted in the book Malcolm X, Black Liberation, and the Road to Workers Power.

Malcolm described his 1964 discussion with the Algerian ambassador in Ghana, “a revolutionary in the true sense of the word.” When they talked about Black nationalism, Malcolm said, the Algerian revolutionary responded, “Well, where did that leave him? Because he was white. … He showed me where I was alienating people who were true revolutionaries dedicated to overturning the system of exploitation.” So, Malcolm told Barnes, “I had to do a lot of thinking and reappraising of my definition of Black nationalism.”

The Algerian Revolution and similar experiences led Malcolm to broaden and deepen his revolutionary internationalist outlook. They drew him to further political collaboration and convergence with the Socialist Workers Party, Koppel noted.

In Malcolm X, Barnes explains in that book, we can see the fact “that, in the imperialist epoch, revolutionary leadership of the highest level of political capacity, courage, and integrity converges with communism, not simply toward the communist movement.

“That truth has even greater weight today as billions around the world, in city and countryside, from China to Nigeria to Brazil, are being hurled into the modern class struggle by the violent expansion of world capitalism.”