The First and Second Declarations of Havana: Manifestos of Revolutionary Struggle in the Americas Adopted by the Cuban People is one of Pathfinder’s Books of the Month for March. The two declarations were adopted by million-strong assemblies of the Cuban people in 1960 and 1962. “What does the Cuban Revolution teach? That revolution is possible,” Cuban leader Fidel Castro explained, reading the Second Declaration to the 1962 Havana rally. The excerpt below is from the preface by Socialist Workers Party leader Mary-Alice Waters, who edited the book. Copyright © 2007 by Pathfinder Press. Reprinted by permission.

Are the program and strategic course that resulted in the victory of workers and farmers in the Bolshevik-led 1917 October Revolution, as well as the debates that led to the formation in 1919 of a new revolutionary international — explained with such clarity by V.I. Lenin — still worth studying a century later? Or are the class forces shaping the world of the twenty-first century so fundamentally different that the Russian Revolution and the trajectory of the first five years of the Communist International are largely irrelevant? Are the political foundations of revolutionary activity today the same as those presented by Karl Marx and Frederick Engels? …

Is socialism a set of ideas? Or is it — as Marx and Engels pointed out in the Communist Manifesto, and as has been confirmed in blood and sweat over a century and a half of popular struggles — the line of march of the working class toward power, a line of march “springing from an existing class struggle, from a historical movement going on under our very eyes”?

Nowhere are these kinds of questions that today confront men and women on the front lines of struggles in Latin America addressed with greater truthfulness and clarity than in the First and Second Declarations of Havana, presented by Cuban prime minister Fidel Castro and adopted by million-strong General Assemblies of the Cuban People on September 2, 1960, and February 4, 1962. That is why Pathfinder decided these declarations need to be broadly available today, presented in a way that helps make them and their interconnections more transparent and accessible to new generations of militants who did not live the tumultuous revolutionary events in the heat of which these documents were forged and signed on to by millions. …

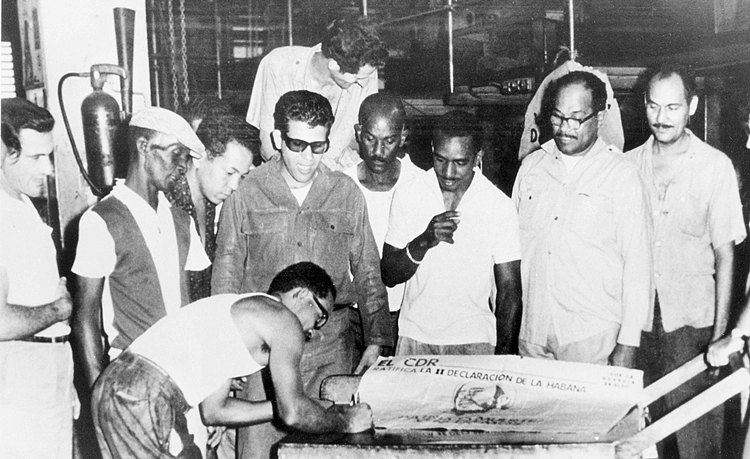

The first National General Assembly of the Cuban People was convoked on September 2, 1960, during the most intense period of mass mobilization the revolution had yet known. In the weeks before and after that outpouring, in response to the imperialists’ increasing acts of armed terror and economic sabotage, hundreds of thousands of workers were taking control of more and more industrial enterprises in Cuba — factory after factory was “intervened,” as Cuban workers termed it, and then nationalized by the revolutionary government.

In June 1960 three major imperialist-owned oil trusts in Cuba had announced their refusal to refine petroleum bought from the Soviet Union. Cuban workers responded by taking control of refineries owned by Texaco, Standard Oil, and Shell and refining the oil themselves. Within days U.S. president Dwight D. Eisenhower ordered punitive action, slashing by 95 percent the quota of sugar Washington had earlier agreed to import during the remaining months of 1960. Within seventy-two hours, the Soviet Union announced it would purchase all Cuban sugar the U.S. refused to buy.

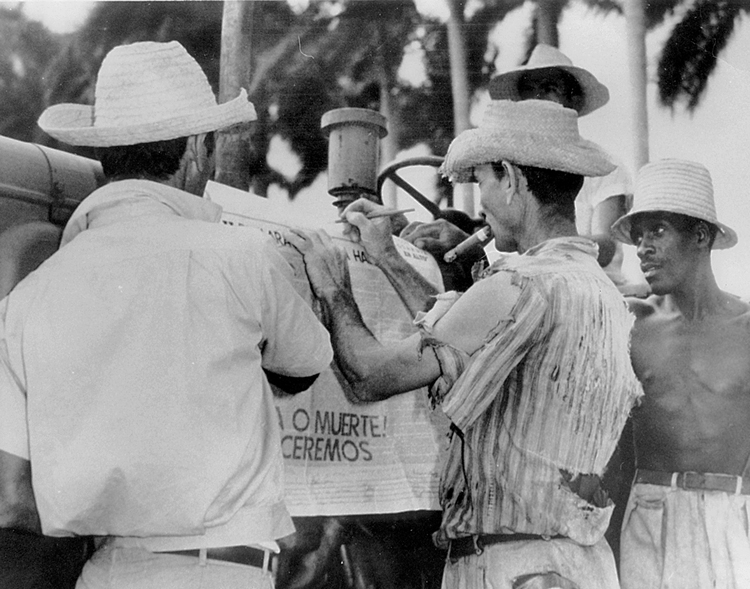

Across the island, Cubans responded by defiantly proclaiming “Sin cuota pero sin bota” — without the U.S. market, but with the imperial boot no longer on our neck.

On August 6, as the capitalists’ economic sabotage escalated, the revolutionary government adopted a decree expropriating the “assets and enterprises located on national territory . . . that are the property of U.S. legal entities.” The following days and nights became known in Cuba as the Week of National Jubilation. Tens of thousands of Cubans celebrated by marching through the streets of Havana bearing coffins containing the symbolic remains of U.S. companies such as the United Fruit Company and International Telephone and Telegraph, tossing them into the sea.

By the end of October, Cuban workers and peasants, supported by their government, had expropriated virtually all imperialist-owned banks and industry, as well as the largest holdings of Cuba’s capitalist class, including such icons as Bacardi rum. Together with the 1959 agrarian reform, which expropriated millions of acres of the largest landed estates and issued titles to some 100,000 landless peasants, property relations in city and countryside had been transformed, definitively establishing the character of the revolution as socialist — the first in the hemisphere — and making clear to all that state power now served the historic interests of working people.

Participating alongside the Cuban people in the events of this historic turning point were many of the nearly one thousand young people from across Latin America, as well as the United States, Canada, the Soviet Union, China, and elsewhere, who had traveled to Cuba to take part in the First Latin American Youth Congress that opened July 26, 1960, in the Sierra Maestra mountains. Among those who that summer were convinced of the necessity, and the possibility, of emulating the revolutionary road traveled by the Cuban people were a good many of the future leaders of revolutionary struggles throughout the Americas. This included young leaders of the Socialist Workers Party and Young Socialist Alliance in the United States.

It was Che Guevara, in his welcoming speech to the youth congress delegates on July 28, who explained to them — and to the world — that “if this revolution is Marxist — and listen well that I say ‘Marxist’ — it is because it discovered, by its own methods, the road pointed out by Marx.”