The “Great Strike” of 1877, sparked by starvation wages and brutal working conditions, started among rail workers and then drew in more than half a million others. It alarmed the capitalist rulers. Federal, state and city governments unleashed troops, cops and gangs of thugs on strikers, cheered on by the bosses’ press. Karl Marx wrote that this mighty class battle “could very well be the point of origin for the creation of a serious workers’ party.” The excerpt below is from “The Railroad Uprisings of 1877,” in American Labor Struggles 1877-1934 by Samuel Yellen. It is one of Pathfinder’s Books of the Month for May. Copyright © 1974. Reprinted by permission from Pathfinder Press.

BY SAMUEL YELLEN

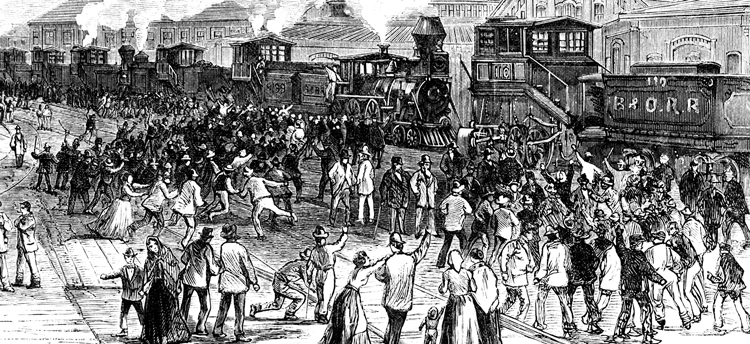

The great railroad strikes which broke out spontaneously and spread with the speed of a plague in the summer of 1877 were the expression of a deep and accumulated discontent. Labor outbreaks had been common in the United States before this time, but had been confined to separate localities. Never before had industry and commerce been confronted with a nation-wide uprising of workers, an uprising so obstinate and bitter that it was crushed only after great bloodshed. The militia of the several states did not suffice; for the first time in the history of the country the federal troops had to be called out during a period of peace in order to suppress strikes. More than a hundred workmen were killed and several hundred badly wounded. For a full week the strikes crowded from the front pages of the newspapers all reports of the war between Russia and Turkey, then in progress, and of the campaign against the Sioux Indians in the Idaho territory. The general public, both workers and employers, became aware that a national labor movement had been born.

Although the strikes were primarily a protest against reductions in wages, they had a more profound origin in the depression that resulted from the panic of 1873. Stimulated by the Civil War, industry and commerce had prospered. For a number of years all kinds of business enterprise had been confidently undertaken. The first transcontinental railroad had been opened in 1869. In the cities, factories had replaced home industry. Immigration had been encouraged and the population had increased. Corporations had sprung up and the foundations for vast fortunes had been laid. This hectic development, however, had been too rapid and was based too often on the wildest gambling and most corrupt scheming. … When the inevitable crash came, hundreds of thousands were thrown out of employment, and many thousands lacked food, clothing, shelter, medical attention. …

The railroads, which had cut wages steadily, prepared for another reduction, in order that freight rates might be lowered. The Pennsylvania Railroad led the way with a 10 per cent cut to take effect June 1. On many other lines — the Erie; Lake Shore; Michigan Southern; Indianapolis and St. Louis; Vandalia; New York Central and Hudson River — a similar reduction was announced for July 1. These notices threw the men, already earning barely enough to support their families, into despair. When they protested against the cuts, their committees were summarily discharged and their small unions dissolved. With thousands of jobless men begging for places, the railroad officials felt certain that the workmen, no matter how intense their dissatisfaction, would be afraid to walk out.

But the railroads failed to calculate the sharp popular feeling against them. Farmers throughout the country resented the high, almost confiscatory freight rates. … Workers were sullen because of continued wage cuts and unemployment, and the railroads, as employers of the largest number of men, stirred up great ill-will. Besides, scandals like that of the Crédit Mobilier and the Union Pacific had disclosed to the public a fraction of the bribery, corruption, and financial thieving that had gone into the building of the railroads. …

From the Baltimore and Ohio, the Pennsylvania, the Erie, and the New York Central roads the “striking mania” rolled westward. Once this stimulus was present, the discontent of railway labor everywhere disclosed itself. Within a week after the first walkout at Camden Junction near Baltimore, strikes had occurred on the Lake Shore; Michigan Central; Pittsburgh, Fort Wayne and Chicago; Pittsburgh, Cincinnati and St. Louis; Vandalia; Ohio and Mississippi; Cleveland, Columbus, Cincinnati and Indianapolis; Chicago, Alton and St. Louis; Canada Southern; and many lesser roads. A few railroads averted strikes by rescinding the orders for wage reductions, but most of them met the strikers’ demands by calling for police and troops. In all sections of the country the people proclaimed their sympathy with the strikers. …

Practically all the strikes had been defeated after the two weeks’ struggle from July 16 to August 1, but not before society saw plainly that the land of opportunity, with its traditions of the sanctity of private property and of freedom of contract, had been converted into the battleground for a bitter war between two essentially hostile economic classes. As the early stages of capitalism, in which numerous small competitive industries flourished and the relations between employer and employee were personal and individual, yielded to a more mature stage, that of the combination and monopolization of industry and finance, fundamental changes occurred in the economic structure of society and in the principles on which it was erected. For the first time in its history the country had been swept by a general-strike movement, and workmen had challenged their employers not as discrete local groups, but as a nation-wide mass. …

[The] strikes in their final stage had to contend against all the military and legal force of the nation.

Nevertheless, the moral effect of the strikes upon the working class was invigorating. A new spirit of labor solidarity was born and made national. The workers understood that the failure of the railroad strikes was due to their want of organization and to the refusal of all branches of railroad labor to act in unison.