On April 9 the National Labor Relations Board released the results of the union vote at Amazon’s fulfillment center in Bessemer, Alabama, where a union drive had been underway since last year.

Of the 5,876 workers eligible to vote, 738 workers voted for the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union to be recognized as the union at Amazon, 1,798 voted against the union, and 2,759 didn’t participate at all. The union has challenged the outcome, saying the company intimidated workers and corrupted the vote. The NLRB has agreed to hear the challenge.

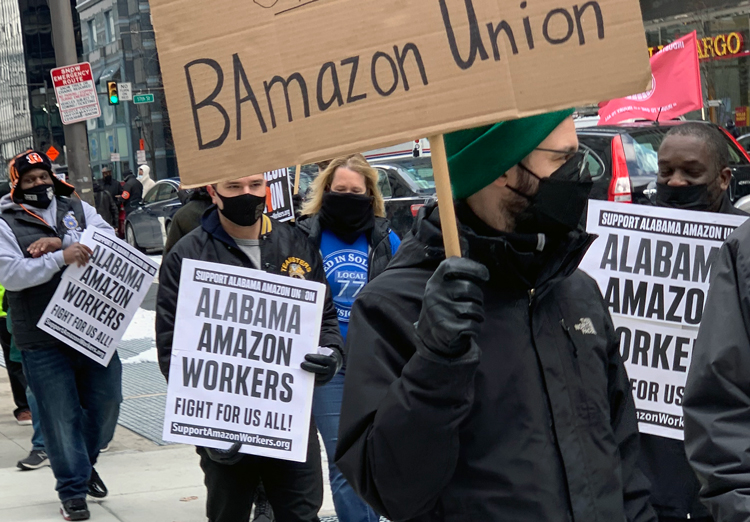

Workers in the Birmingham-Bessemer region had followed the organizing drive with interest and, for many, with support. There is a long history of union struggles in coal mining, steel and other industries in the area. Even with the severe contraction of these industries in recent decades, union ties remain stronger than in many places.

Socialist Workers Party campaigners went door to door in working-class areas of Bessemer and nearby Hueytown in the months leading up to the vote. We spoke with workers in all kinds of jobs — from coal miners to fast-food workers to other warehouse workers and more — who were hoping for a union win.

Amazon workers and others we met, some of whom had worked there and quit, confirmed the difficult work conditions, long hours, inadequate pay, and disrespect from the bosses that fueled the organizing drive.

Other workers weren’t so sure a union would help and voiced concern that Amazon might shut down if the union won. Some, especially younger workers, didn’t really know what a union was. Bessemer, like many other working-class cities, has long faced high unemployment, so when Amazon opened in March 2020 the company’s offer of a $15-an-hour wage with health insurance drew workers from far and wide.

A group of workers inside the Bessemer warehouse got together within a few months after it opened, determined to fight for a union, and got a positive response from the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union. Over the next few months they got several thousand workers to sign union cards asking the NLRB to authorize an election, a sign that the union effort had struck a chord.

The decision to try to organize was a bold one. They were taking on one of the largest U.S. corporations, whose bosses had fought tenaciously to keep unions out of all its U.S. facilities. For this reason, the drive drew attention in the media.

A union victory in Bessemer would give a boost to workers organizing at other Amazon facilities, as well as by workers at Walmart, where I work. It would impact Target, and all kinds of other companies where workers face similar grueling, unsafe conditions and inadequate wages — more and more the norm for workers nowadays.

What is the road forward?

Since the vote, there have been articles in the capitalist media about why the union lost, and by such a large margin. Some pundits say the vote was a “major defeat” for building the labor movement. Workers discussing what happened and trying to draw some lessons for the future should reject this view.

The organizing drive in Bessemer showed that hundreds of workers were ready and willing to stand up to the company’s anti-union campaign of lies, threats and intimidation and to fight to change conditions there.

They didn’t get defeated because wages and working conditions are so great under capitalism today. Rather it’s because the union officialdom all too often forgets the lessons of what it took to organize the CIO industrial unions in the 1930s.

For decades the union movement has been in decline. Today only 6% of workers in private industry are union members.

The officialdom has become increasingly tied to class collaboration, relying on “common interests” with the bosses and help from “friends of labor” in the Democratic Party. Today they are hailing President Joseph Biden and the Protecting the Right to Organize Act he’s promoting, which would tie organizing workers to government regulations, not to their own fighting capacities. The officials less and less look to rely on the workers themselves as the source of the unions’ power.

There was no serious effort to organize the Amazon workers themselves to help lead in winning support in the plant, or in organizing workers in Alabama and across the country to build the kind of social movement powerful enough to win.

Reliance on “social media” and support for the union drive from “celebrities” and a handful of Democratic Party politicians couldn’t substitute for this.

Workers and our unions will learn from our struggles to rely on ourselves, not the capitalist government, their parties and more red tape and labor legislation. We will be able to use our unions to organize and fight effectively again.

There are stirrings in the working class today, with workers on strike or locked out by bosses at Warrior Met coal mines in Alabama, at ATI steel, Marathon Petroleum in Minnesota, and more.

For every worker looking to learn from the experiences of the mass working-class mobilizations that organized the CIO in the 1930s, there is no better place to go than Teamster Rebellion by Farrell Dobbs. He was a participant and leader in those struggles. This book “is not a ‘manual’ or a handbook,” Jack Barnes, national secretary of the Socialist Workers Party, writes in his introduction. “It is the record of a concrete experience in the class struggle — one that can be studied and absorbed by class-conscious workers and farmers who find themselves in the midst of other struggles, at other times, in other conditions.”

Experiences like the one in Bessemer show that potential and can be built on to take the next steps forward.