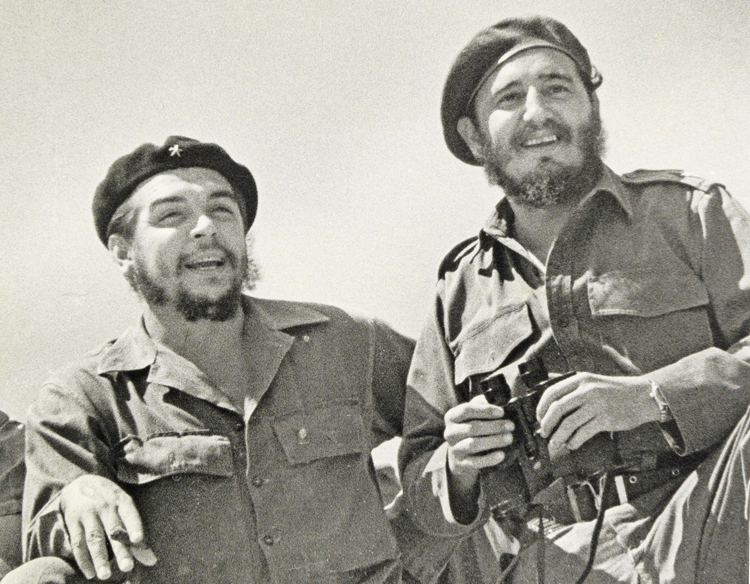

Che Guevara Talks to Young People is one of Pathfinder’s Books of the Month for December. Ernesto Che Guevara was an Argentine-born revolutionary who joined Fidel Castro and his Rebel Army, becoming an outstanding leader of the Cuban Revolution. They led workers and peasants to take power in 1959, opening the road to socialist revolution in the Americas. The Marxist example of leaders like Castro and Guevara initiated a renewal of communism, inspiring a new generation of revolutionary-minded youth worldwide. The excerpt is from “Something New in the Americas,” the speech given by Guevara to the First Latin American Youth Congress, held in Havana, July 28, 1960. Copyright © 2000 by Pathfinder Press. Reprinted by permission.

BY ERNESTO CHE GUEVARA

Many of you, from diverse political tendencies, will ask yourselves, as you did yesterday and as perhaps you will also do tomorrow: What is the Cuban Revolution? What is its ideology? And immediately a question will arise, as it always does in these cases, among both adherents and adversaries: Is the Cuban Revolution communist? Some say yes, hoping the answer is yes, or that it is heading in that direction. Others, disappointed perhaps, will also think the answer is yes. There will be those disappointed people who think the answer is no, as well as those who hope the answer is no.

I might be asked whether this revolution before your eyes is a communist revolution. After the usual explanations as to what communism is (I leave aside the hackneyed accusations by imperialism and the colonial powers, who confuse everything), I would answer that if this revolution is Marxist — and listen well that I say “Marxist” — it is because it discovered, by its own methods, the road pointed out by Marx. [Applause] …

The Cuban Revolution was moving forward, not worrying about labels, not checking what others said about it, but constantly scrutinizing what the Cuban people wanted of it. And it quickly found that not only had it achieved, or was on the way to achieving, the happiness of its people; it had also become the object of inquisitive looks from friend and foe alike — hopeful looks from an entire continent, and furious looks from the king of monopolies. …

[E]ven though there is certainly continuity, the Cuban Revolution you see today is not the Cuban Revolution of yesterday, even after the victory. Much less is it the Cuban insurrection prior to the victory, at the time when those eighty-two youths made the difficult crossing of the Gulf of Mexico in a leaky boat, to reach the shores of the Sierra Maestra. Between those youths and the representatives of Cuba today there is a distance that cannot be measured in years — or at least not accurately measured in years, with twenty-four-hour days and sixty-minute hours.

All the members of the Cuban government — young in age, young in character, and young in the illusions they held — have nevertheless matured in the extraordinary school of experience; in living contact with the people, with their needs and aspirations. …

The peasants taught us their know-how and we taught the peasants our sense of rebellion. And from that moment until today, and forever, the peasants of Cuba and the rebel forces of Cuba — today the Cuban revolutionary government — have marched united as one.

The revolution continued progressing, and we drove the troops of the dictatorship from the steep slopes of the Sierra Maestra. We then came face-to-face with another reality of Cuba: the worker — both agricultural and in the industrial centers. We learned from him too. … We learned the value of organization, while again we taught the value of rebellion. And out of this, organized rebellion arose throughout the entire territory of Cuba. …

What I am saying to you, young people from throughout the Americas who are diligent and eager to learn, is that if today we are putting into practice what is called Marxism, it is because we discovered it here. …

For the first time in Latin America, this revolution carried out an agrarian reform that attacked property relations other than feudal ones. There were feudal remnants in tobacco and coffee, and in these areas land was turned over to individuals who had been working small plots and wanted their land. But given how sugarcane, rice, and cattle were worked in Cuba, the land involved was seized as a unit and worked as a unit by workers who were given joint ownership. They are not owners of a single parcel of land, but of the whole great joint enterprise called a cooperative. This has enabled our deep-going agrarian reform to move rapidly. …

A revolutionary government is one that carries out an agrarian reform that transforms the system of property relations on the land — not just giving the peasants land that was not in use, but primarily giving the peasants land that was in use, land that belonged to the large landowners, the best land, with the greatest yield, land that moreover had been stolen from the peasants in past epochs. [Applause]

That is agrarian reform, and that is how all revolutionary governments must begin. On the basis of an agrarian reform the great battle for the industrialization of a country can be waged, a battle that is not so simple, that is very complicated, and where one must fight against very big things. …

[W]e will not tolerate anyone telling us what to do. Because we were here on our own up to the last moment, awaiting the direct aggression of the mightiest power in the capitalist world, and we did not ask help from anyone. We were prepared, together with our people, to resist up to the final consequences of our rebel spirit.

That is why we can speak with our head held high, and with a very clear voice, in all the congresses and councils where our brothers of the world meet. When the Cuban Revolution speaks, it may make a mistake, but it will never tell a lie. From every tribune from which it speaks, the Cuban Revolution expresses the truth that its sons and daughters have learned, and it always does so openly to its friends and its enemies alike.