When we pay tribute to Fidel, we are, above all, paying tribute to the working people of Cuba, to the men and women of José Martí, of Antonio Maceo. Fidel was one with them. His greatest achievement was forging in struggle a revolutionary cadre, a communist cadre, capable of leading the workers and farmers of Cuba to establish the first free territory of the Americas and to successfully defend it for more than six decades.

During the early years of the revolution, in 1964, Fidel explained to the world how the working people of Cuba shaped him and made him who he became. I, too, once belonged to an organization, he said, referring to the July 26 Movement. “But the glories of that organization are the glories of Cuba; they are the glories of the people; they belong to all of us. And there came a day that I stopped belonging to that organization.”

As the Freedom Caravan moved through the towns and cities of Cuba in the first days of January 1959, along the road from Santiago to Havana, Fidel said, “I saw lots of men and women, hundreds and thousands of men and women with the red and black uniforms of the July 26 Movement. But many thousands more wore uniforms that weren’t black and red but were the work shirts of workers and farmers and other men and women of the people.”

We realized “we had truly accomplished something that was greater than ourselves,” Fidel said.

“They are the strength, the backbone of the revolution! Fist, arm, muscle of the revolutionary people, of the working class, of the peasants, of the workers!”

Peoples of Cuba and the world

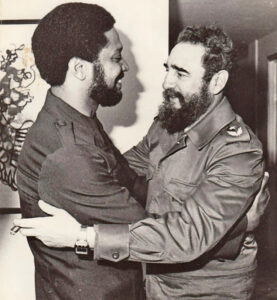

If Fidel belongs first to the working people of Cuba, however, he also belongs to the oppressed and exploited peoples of the world over. And under his leadership, from Latin America and the Caribbean, to Africa and Asia, to North America and Europe, working people of Cuba have shown us in action what proletarian internationalism means.

They have shown us that the internationalism of the working class in power is not primarily a foreign policy. It must be an extension of the revolution itself, inseparable from its strength — even its survival. Fidel explained this to the Cuban people with crystal clarity in July 1976, during the earliest days of Cuba’s internationalist mission to aid the people of Angola and Namibia, who were facing the aggression of the apartheid regime of South Africa and its Washington promoters.

In Fidel’s memorable words, “Those not willing to fight for the freedom of others will never be able to fight for their own.”

Some 15 years later, in May 1991, Raúl closed that chapter of history, which by all measures stands as Cuba’s greatest act of international solidarity. Cuba was already confronting some of the most difficult days of the revolution, the Special Period, precipitated by the implosion of the Soviet bloc and sudden evaporation of some 85 percent of the country’s trade relations.

Receiving the last of the Cuban volunteers returning to Cuban soil, Raúl drew the balance sheet: “When we face new and unexpected challenges we will always be able to recall the epic of Angola with gratitude, because without Angola we would not be as strong as we are today.”

Moral strengths of leadership

Where did Fidel’s moral strengths as a leader of Cuba’s working people come from? His ability to lead them to accomplish the epic feats of Cuba’s socialist revolution?

He gave us a piece of the answer in the tribute he paid Ernesto Che Guevara in 1987 on the 20th anniversary of Che’s death in combat.

“Che believed in man,” Fidel said.

“And if we don’t believe in man, if we think that man is an incorrigible little animal, capable of advancing only if you tempt him with a carrot or hit him with a stick—anyone who believes this will never be a revolutionary, will never be a socialist, will never be a communist.”

Those were not empty words. Fidel was laying out the ethical foundation, the proletarian morality, our morals, that guided his own course of action, his leadership example, throughout his life. The examples and testaments to this are countless.

Never killed a prisoner

“The Rebel Army and the militia never killed a prisoner, tortured a prisoner, nor abandoned a single wounded enemy soldier,” explained José Ramón Fernández, commander of the main column of revolutionary forces that routed the U.S.-backed invasion at the Bay of Pigs in 1961. “Not during the struggle in the Sierra, not in the struggle against the bandits, not at Girón.

“That is a matter of principle, of ethics, in our armed forces, one Fidel has strictly demanded from the beginning of the revolutionary struggle.”

From the very first battle in the Sierras, “our medical supplies were used for all the wounded, without distinction,” both the Rebel Army’s and those in Batista’s armed forces, Fidel said in Ignacio Ramonet’s 100-hour interview with the Cuban leader.

“Captured soldiers were allowed to go absolutely free,” Fidel said. “We had an invariable policy of respect for the adversary’s integrity. … There were cases of enlisted men who surrendered as many as three times, and three times we would release them.”

Since we disembarked from the Granma, Fidel underlined, our guidelines have been “no assassination, no civilian victims, no use of the methods of terror,” no acts “in which innocent people might be killed. That’s not contemplated in any revolutionary doctrine.

“No war is ever won through terrorism. It’s that simple,” Fidel said. Because if you employ terrorism, “you earn the opposition, hatred and rejection of those whom you need in order to win the war.” That’s why at the end of the war “we had the support of over 90 percent of the population.”

“For us it was a philosophy, a principle, that innocent people must not be sacrificed. It was always a principle — practically a dogma.

“Batista’s soldiers would go around stealing, burning houses and killing people,” Fidel told the interviewer. “The campesinos could see that we, on the other hand, respected them. We paid them for the food and other things we got from them.”

Without those policies, “we’d never have won the war.”

Families of those killed in the war

Teté Puebla was second in command of the Rebel Army’s women’s platoon created by Fidel and later the first woman to reach the rank of general in Cuba’s Revolutionary Armed Forces. In her account, Marianas in Combat, she describes how the mothers, widows, and children of Batista’s soldiers who died in combat were treated.

The widows weren’t to blame “for the murders the army of the dictatorship committed,” she said. “So we looked after them in the same way. … Whenever we set up a school with a group of children, we didn’t say who their parents were. Only those of us in charge of them knew. We protected these children,” she said. Now they are part of the revolution. “The widows and mothers of the Batista army collect a pension.”

“We identify with all peoples of the world who fight against misery and hunger,” Teté said. “These principles of the revolution are the moral foundation of our struggle.”

The value of a human life

As the commander-in-chief of the Revolutionary Armed Forces, Fidel was deeply concerned not only for the physical well-being of his forces and the care of the wounded. He was concerned for their mental health, their humanity.

Harry Villegas, known the world over by the nom de guerre Pombo — given him by Che, as they fought side by side in the Congo in 1965 — served for more than five years as the liaison between the Cuban high command in Angola and the FAR special command post in Havana, headed by Fidel. In Pombo’s book Cuba and Angola: The War for Freedom, he recounts a telling example of Fidel’s vigilance over the moral conduct of the Cuban internationalists during the Angola mission — not only of their actions, but even the perception of those actions.

“There was an incident in which a Cuban pilot mistakenly dropped bombs on a home in a quimbo, a hamlet, and some civilians were killed,” Pombo recounted. “Fidel insisted the pilot be tried in Angola under that country’s laws. [Angolan President Agostinho] Neto said it hadn’t been done deliberately; the pilot wasn’t prosecuted. …

Nonetheless, Pombo continued, “Fidel gave the order that the pilot be withdrawn from the war. War starts to affect a person’s psychology, he said. Your interaction with death can begin to lessen how you value life; you start getting accustomed to death.

“Fidel sought in every way to prevent us from becoming psychologically warped and turned into people for whom life had no value.”

No crime in name of revolution

These same moral foundations underlay the outrage — and bitterness — Fidel expressed on learning of the assassination in 1983 of Maurice Bishop, the central leader of the revolutionary government of the East Caribbean island of Grenada. During a counterrevolutionary coup by a faction led by Bernard Coard, Bishop and other revolutionary leaders were murdered by soldiers acting on orders by Coard’s clique. Working people and youth who had poured into the streets to defend the revolution were also killed.

“No doctrine, no principle or position held up as revolutionary, and no internal division, justifies atrocious proceedings like the physical elimination of Bishop and the outstanding group of honest and worthy leaders killed yesterday,” Fidel announced publicly the very next day.

“No crime must be committed in the name of the revolution and freedom.”

It was the same principles that led Fidel in 2008 to publicly condemn the course of the Manuel Marulanda leadership of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) for kidnapping civilians and holding them hostage, sometimes for years under harsh jungle conditions. “These were objectively cruel actions,” Fidel wrote in an article July 3, 2008. “No revolutionary aim could justify them.”

And it was the same moral foundation that led Fidel in 2010 to not only recognize the national aspirations of the Palestinian people but also to speak out in unequivocal terms against the Holocaust denial of then Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

“I don’t think anyone has been more slandered than the Jews,” Fidel said in a widely published interview. The Jews have “lived an existence that is much harder than ours. There is nothing that compares to the Holocaust.”

“Without a doubt” the state of Israel has the right to exist, Fidel said.

* * *

I’ll finish with one last example.

One of the greatest moments of Fidel’s international leadership came in 1979, when he addressed the United Nations General Assembly in New York City on behalf of the Movement of Nonaligned Countries, whose presidency he had recently assumed.

“I have not come to speak about Cuba,” he told the delegates.

“I do not come to denounce before this assembly the aggressions to which our small but honorable country has been subjected for twenty years. Nor have I come to offend with unnecessary adjectives the powerful neighbor in his own house,” he said.

“I speak on behalf of the children of the world who do not have even a piece of bread.”

In the mouths of many, those words would have been sentimental, hollow rhetoric. Coming from Fidel, they captured the course of his lifetime.