“The Movement and the ‘Madman,’” a new PBS documentary, offers a version of the movement against the Vietnam War in 1969 that blames President Richard Nixon for the war and plays up the role of the Democratic Party that year in the Vietnam Moratorium. The demonstrations drew hundreds of thousands into their first protests and attracted working people.

Some 8 million U.S. military personnel were deployed in the course of the Southeast Asian War against the struggle of the Vietnamese people for self-determination and to reunify their country.

Washington went down to a historic defeat in 1975. Vietnam was reunified and capitalist property relations were overturned a few years later.

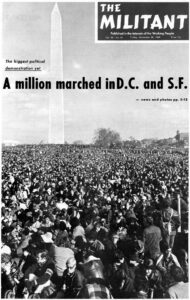

In the midst of a shooting war, more and more working people in the U.S. began to question it and an anti-war movement — unprecedented in wartime in U.S. history — grew. The largest ever anti-war demonstrations were organized, having a powerful impact on the ranks of the armed forces. The movement was deeply intertwined with the ongoing struggle against Jim Crow segregation.

Produced and directed by Stephen Talbot, “The Movement and the ‘Madman’” focuses on 1969. It shows interviews with some leaders of the Moratorium, footage of the massive demonstrations in October and November, and interviews with government officials. Nixon planned to “threaten the North Vietnamese with nuclear weapons,” Morton Halperin, then an aide to Nixon’s Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, says. “To make that threat credible,” Nixon wanted “the Vietnamese to fear he was crazy and might actually do this.”

Nixon would later admit the spread of anti-war protests helped to destroy “the credibility of my ultimatum to Hanoi.”

Early in the film David Hawk, one of the organizers of the Oct. 15, 1969, Moratorium, heaps praise on the “courage” of congressional representatives who joined anti-war actions. Their speeches on the steps of the Capitol are shown prominently. David Mixner, another organizer of the October Moratorium proudly tells filmmakers that Bill Clinton, then working as an intern for a senator, visited him at the Moratorium’s office.

Anyone looking for an account of the class forces that ended the war, and the working-class perspective of many who led the fight, would do well to pick up a copy of Fred Halstead’s Out Now! A Participant’s Account of the Movement in the U.S. Against the Vietnam War. Halstead was one of the organizers of the 1969 anti-war demonstrations and had been Socialist Workers Party candidate for president in 1968. He describes how the war was escalated by the previous Democratic Party administrations of John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. “Dove politicians didn’t lead,” Halstead writes, “they followed, far behind.”

“Even after the dramatic switch in public attitude” toward the war “made dovishness permissible on Capitol Hill,” Halstead said, “the vast majority in both parties — doves included — consistently voted for the Vietnam military budget up to 1973.”

U.S. rulers forced out of Vietnam

“For all their tactical disputes,” Halstead writes, the rulers “never did change their minds about their right to brutalize Vietnam to keep a piece of it under U.S. domination.”

“They were forced — first of all by the resistance of the Indochinese peoples but also by the American anti-war movement and international opposition to the U.S. role,” he said. “They backed off, bit by bit, brutalizing as much as they could get away with, all the way to the end.”

Little mention is made in the film of the huge impact of the Black-led working-class movement for civil rights underway as the war took place. That successful struggle transformed the attitudes and the self-confidence of millions, giving momentum to those protesting the war here and in the army.

“The Movement and the ‘Madman’” barely mentions the shifts already taking place among U.S. soldiers. By 1971, “the morale, discipline and battle-worthiness of U.S. Armed Forces,” wrote the Armed Forces Journal, was “worse than at any time this century.”

By focusing heavily on Nixon’s plans to threaten a nuclear attack, the film minimizes the actual horror inflicted by Washington on the Vietnamese people, including carpet bombings and widespread use of napalm.

Some 60,000 U.S. soldiers were killed in the war. Millions of inhabitants of Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia lost their lives as the U.S. rulers dropped more bombs than in all previous wars combined. From 1962 to 1971, their forces sprayed 21 million gallons of defoliants across southern Vietnam. Agent Orange, known to produce cancer, was widely used, turning vast tracts into wastelands. Thousands of U.S. veterans suffer from the effects of Agent Orange today.

Nixon’s nuclear threats were not those of a “madman,” any more than the sharp escalations of the war by Johnson.

The anti-war mobilizations “changed the political face of the United States and motivated a healthy distrust of the rulers in Washington,” Halstead concludes.

“It broke the fever of the anti-communist hysteria and weakened the efficacy of the red scares,” he said. It challenged “the image of GIs as obedient pawns of the brass immunized against dissenting currents within the civilian population.”

Today, sharpening conflicts among the world’s capitalist powers accelerated by Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine, and the ensuing worldwide arms race, point toward inevitable wars to come. Halstead’s account of the class forces that came together against the Vietnam War is essential reading.