From the Escambray to the Congo: In the Whirlwind of the Cuban Revolution by Víctor Dreke is one of Pathfinder’s Books of the Month for September. As a high school student, Dreke joined Cuba’s revolutionary movement, then became a Rebel Army combatant. After the 1959 triumph, as the socialist revolution deepened, Dreke served as a commander of the volunteer battalions that took the revolution into the Escambray mountains and defeated counterrevolutionary bands there. Later, he became Che Guevara’s deputy in Cuba’s internationalist mission in the Congo. For decades he served as a representative of the Cuban Revolution throughout Africa as well as a political leader at home. The excerpt is from “‘Lucha Contra Bandidos’ in the Escambray.” Copyright © 2002 by Pathfinder Press. Reprinted by permission.

In Cuba at the triumph of the revolution there were a half million illiterates, and there were another half million who were only semiliterate. That was the concrete situation. If one were to go to Pinar del Río or to the Escambray the situation was terrible. There was no electricity, no running water — what little water there was came from wells. There were no stores. There were few radios, since you couldn’t even receive radio signals throughout much of these mountainous areas. All this made the enemy’s job easier.

From the time of the revolutionary war, nearly all these individuals I’ve talked about — who would eventually become counterrevolutionaries — were concentrated in the Escambray. They worked on some peasants and managed to recruit a few. At the same time, they also committed abuses in the areas where they functioned. They murdered peasants, they raped peasant women. They burned down schools and homes. So the peasants were terrorized; they were deathly afraid of the counterrevolutionaries. Some peasants joined them consciously, of course, but others joined out of fear. This is how the counterrevolutionary movement was built. …

One of those in charge of the agrarian reform there, for example, was the counterrevolutionary Evelio Duque. … Duque headed up INRA [National Institute of Agrarian Reform] in Sancti Spíritus, and he removed the compañeros who were revolutionaries from the agrarian reform and its leadership. He removed people like Commander Julio Castillo, a revolutionary who was highly regarded in Sancti Spíritus. Then Duque recruited others who, like himself, weren’t revolutionaries.

What did Duque do? He committed a series of injustices. He expropriated land that shouldn’t have been taken. Or else he extorted money in exchange for not expropriating someone’s land.

So the agrarian reform wasn’t implemented as the commander in chief [Fidel Castro] and the revolutionary leadership had laid out in the Agrarian Reform Law. Nor as Che [Guevara] and the compañeros of the [Revolutionary] Directorate had done during the war. …

The conscious revolutionaries at that time were not yet Marxists or Leninists — and I’m not just speaking about myself — but at least we wanted a revolution. We wanted to prevent the bourgeoisie from returning to power. We wanted the poor to be in charge. We wanted racial equality. That’s what we were then.

But the fact is we gave the Escambray to the bandits as a gift during the first stage. That has to be said.

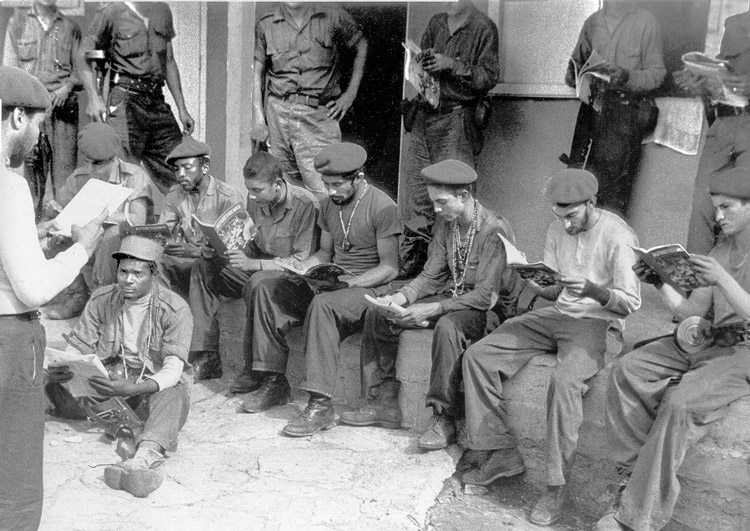

When the first clean-up operation began in 1960, when the army arrived, when Fidel arrived, the peasants responded, and entire battalions of peasant militias from the Escambray were formed. The peasants asked for weapons and they defended the Escambray. So what the enemy thought was going to be a den of thieves was, by determined revolutionary combat, turned into a bulwark of the revolution. …

The first clean-up operation in the Escambray ran from the end of 1960 through the first months of 1961. But we had to withdraw our troops with a few bands still remaining. And then in April came Playa Girón.

We withdrew our troops early on in 1961 because they had already been mobilized for months. They were workers and peasants who had voluntarily left their workplaces and were absent from their jobs. Since they were taking part in the clean-up operation, they weren’t producing. It’s important to remember that the enemy used the counterrevolutionary bands in the Escambray to try to drain the resources of the fledgling revolution, which was fighting to resolve the country’s economic problems.

Most militia volunteers weren’t getting paid anything. For those who had jobs, their factories and workplaces continued to pay their wages to their families. …

These bandits were dependent on imperialism. We can’t look at the bandits in isolation, on their own, as just some group of crazies who took up arms. No, no, no. This was organized. They were being organized as a fifth column to back an invasion by the United States. An important mission was assigned to these bandits by Washington.

At the time of the first clean-up, the mission for which the bandits were being prepared was to attack and seize the main towns when the invasion came — Trinidad and all those little towns there — and to take the highways. In addition, within the cities it was expected that organized counterrevolutionaries would take up arms when the moment came.

In other words, all this was being directed by imperialism.

What happened?

The commander in chief, Fidel, led the process of eliminating the bands prior to Girón. The murder and harassment of peasants had to be stopped. What’s more, we knew an attack was coming. There had already been various types of sabotage actions by the bandits in different regions. For example, near Trinidad they blew up fuel tanks.

We made the effort to rapidly clean up the Escambray, so we wouldn’t face a fifth column already armed and trained.

When the landing came at Girón, very few of the bandits remained. They were in flight. They were in hiding. They controlled nothing. This was part of defeating the U.S. invasion plan. The invaders were left without a rear guard.