Crushing the Ukrainian nation and its people is at the heart of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s determined effort to reestablish the Russian Empire with himself as czar. But his invasion has run up against fierce Ukrainian resistance, with working people fighting to defend their country’s independence and reestablish sovereignty over all occupied territory in eastern and southern Ukraine and in Crimea.

Ukrainian missiles struck a Russian navy yard in Sevastopol, Crimea, Sept. 13, severely damaging two warships and the dry docks. Another Russian ship near the port was hit by a Ukrainian drone the next day. In recent weeks, Ukrainian forces have also hit two of Moscow’s six radar and missile-launch batteries in Crimea.

The strikes were aided by “ordinary residents of Sevastopol who constantly send us information about Russian troops,” according to Atesh, a Crimean Tatar-led underground movement. Its name means “fire” in the Turkic language of the Crimean Tatars.

In 1944 troops under orders of the Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin forcibly deported the entire Tatar population of Crimea to Central Asia, claiming they were German agents. During the upheaval more than a third died. The survivors and their descendants were only allowed to return to their homeland decades later.

As the Putin regime invaded Crimea in 2014, tens of thousands mobilized to protest, especially Tatars. Moscow’s forces have responded by raiding homes, mosques and schools; shutting down Tatar newspapers; and banning the Mejlis, the Tatar national council, and its leaders, including Mustafa Dzhemilev.

From Kyiv, Dzhemilev told the Guardian in July that the Atesh opposition group is made up of Crimean Tatars and other Ukrainians, as well as some Russians. Working underground behind Russian lines, it has carried out several sabotage attacks, without any arrests so far. The group appeals to Russian soldiers to stop fighting. It expects to recruit hundreds of young Crimean Tatar men for armed resistance when the Ukrainian army’s push south reaches Crimea.

While only 13% of Crimea’s population are Tatars, they make up the great majority of those arrested or kidnapped by Moscow’s occupation forces.

Among the Crimean Tatars fighting today in Ukraine’s Territorial Defense Force is Ismael Ramzanov. He had been arrested and beaten in Crimea by the occupation forces in 2018 after organizing protests against the jailing of Tatar political prisoners. Released a year later, he went to Kyiv.

No free Crimea if Ukraine isn’t free

“I left my small homeland to protect my big homeland,” he told Al Jazeera last year. “I know that without a free Ukraine, there will be no free Crimea.”

Said Ismahilov, a former Islamic scholar, now works as a frontline medic alongside Ukrainian soldiers. Like many working people in Ukraine, he volunteered to defend the country as Russian tanks advanced on Kyiv, at the start of the invasion. He became the army’s first Muslim chaplain.

“I’m more used to my country doing this than if I were closing my eyes in quiet prayer somewhere far removed from the conflict zone,” he told Al Jazeera. In 2014 Moscow-led separatists seized his native city, Donetsk, in eastern Ukraine. An outspoken leader of a small, long-established Muslim community there, he fled from arrest. His parents were Penza Tatars who came from central Russia. They are the second-largest group of Muslims in Ukraine after Crimean Tatars.

During the Bolshevik Revolution under V.I. Lenin’s leadership for several years from 1917, Tatars, like other Muslim minorities, were granted religious, cultural and language rights. But once a counterrevolution led by Stalin took hold, Moscow’s domination and repression of rights was reimposed.

In the Soviet republic of Ukraine in the 1980s there were no officially recognized Muslim communities. But since the collapse of the Soviet Union and Ukraine regaining its independence, its government has recognized 700 Muslim communities, covering 600,000 people.

Under Moscow’s current occupation of eastern Ukraine, many mosques there have been destroyed and religious leaders targeted.

Anti-war protests

In contrast to the courageous determination that marks Ukraine’s fighting forces, the Russian army has suffered demoralizing losses despite the Kremlin commanding greater resources and a population nearly four times the size of Ukraine’s. Many Russian working people used at the front as Moscow’s cannon fodder are exhausted.

Putin is wary about launching another mobilization to replenish his forces for fear of setting off deeper opposition to his war. Despite jailing political opponents and suppressing mass protests against his conscription orders last fall, public demonstrations against the war continue.

On Aug. 20 four individuals in different locations in Russia held one-person anti-war protests. Before being arrested, Anton Malykhin was hugged by a passer-by in the center of Moscow as he held up his placard, saying “No to the war.”

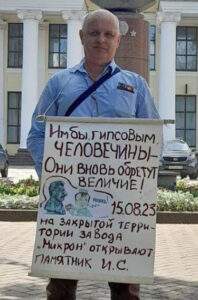

Five days earlier, retiree Andrei Ivanov protested the erection of a statue to Stalin at the gate of the Mikron factory in Velikiye Luki, west of Moscow. Putin has encouraged monuments to Stalin in an attempt to try to identify his regime’s murderous assault on Ukraine’s independence with the heroic struggle of the people of the Soviet Union that defeated the invasion of the country by the German army in the Second World War.

Stalin was “a tyrant, a murderer, an authoritarian” Ivanov said. His protest was “not only an act against the monument, but also against the war” in Ukraine.