HAVANA — The life of Juan Almeida Bosque, a central leader of the Cuban Revolution for more than five decades, was highlighted at two events during the recent Havana International Book Fair here. They showed the revolutionary integrity, courage, discipline, and selflessness — the working-class political qualities — of the men and women who, under Fidel Castro’s leadership, carried out Cuba’s socialist revolution. Almeida, who died in 2009, was one of those outstanding leaders.

‘‘I first met Fidel in 1952,” Almeida says in the documentary film “Conversando con el comandante Juan Almeida Bosque” (Conversation with Commander Juan Almeida Bosque), which was shown here Feb. 17. He explains that Fulgencio Batista had just carried out a military coup March 10, 1952, and many young people rushed to the University of Havana after hearing that opponents of the coup were organizing there.

Almeida met Fidel Castro there. He says he was surprised, but also interested, that Castro was carrying under his arm a book by V.I. Lenin, the central leader of the 1917 Bolshevik-led Russian Revolution.

“I was not a communist then,” Almeida tells filmmaker Estela Bravo in the 1996 documentary. He says he was concerned about the miserable conditions facing workers and peasants in capitalist Cuba, from joblessness to racial discrimination against black workers like himself.

“I only became a communist after the victory of the revolution” in 1959, Almeida says. Through the experiences he gained as a cadre and then a commander of the Rebel Army, “I embraced the cause of socialism — and I will die with that conviction. I have been a soldier of this revolution.”

The film showing was held at Casa de África, a museum and cultural center focused on Cuba’s African roots, founded in 1986 at the initiative of Almeida and Havana historian Eusebio Leal.

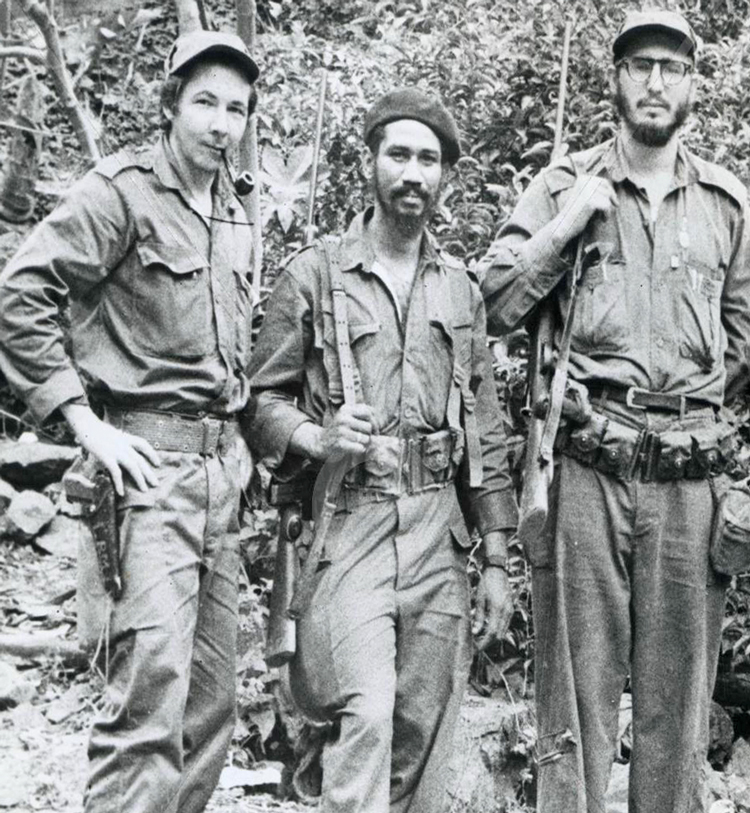

At the meeting, chaired by Casa de África Director Alberto Granado, Víctor Dreke and Heriberto Feraudy gave a vivid picture of Almeida. Today president of the Cuba-Africa Friendship Society, Dreke was a Rebel Army combatant during the revolutionary war. He was second in command to Ernesto Che Guevara in the 1965 Cuban volunteer mission backing anti-imperialist combatants in the Congo. Afterward he led the Cubans who fought alongside pro-independence forces in Guinea-Bissau.

When Almeida was president of the Association of Combatants of the Cuban Revolution, Dreke worked closely with him. The association organizes several generations of revolutionary fighters who educate young people about Cuba’s revolutionary history and why it’s important to know it.

Feraudy is a well-known writer on Afro-Cuban history, and has served as Cuba’s ambassador in several African countries.

Born into a black working-class family in Havana, Almeida worked as a bricklayer from age 11. When Castro recruited him to the revolutionary movement, the underground cell he joined was made up of several construction workers like himself. From that point on, Almeida was a leading participant in all the decisive moments of the Cuban Revolution.

Almeida won respect among the Cuban people for his many accomplishments, Feraudy said, not only as a political leader — including a fighter against racist prejudice — but as an author of books on the revolutionary struggle, and a composer of popular songs. “But first and foremost, Almeida was a disciplined revolutionary, a communist.”

This was also the theme of a Feb. 24 presentation of the book Juan Almeida Bosque: Testimonios de un santiaguero 1970-2009 (Juan Almeida Bosque: Eyewitness Account of a Santiago Resident, 1970-2009), by Luis Estruch. As a government official in Santiago de Cuba, Estruch worked with Almeida over four decades.

Almeida was part of the July 26, 1953, attack on the dictatorship’s Moncada barracks in Santiago, Estruch said. Although that action failed, it launched the revolutionary struggle that opened the door to the first socialist revolution in the Americas.

During the Batista regime’s trial of the Moncada rebels, the prosecutor asked Almeida, “You surely must have wanted the revolution to be victorious so you could give the orders?”

No, “I wanted the revolution to be victorious so it would be the people who give the orders,” Almeida replied. “Because up to now, others have given the orders, and things have not gone well.”

Almeida, Castro, and other rebel fighters were convicted and jailed until 1955, when they were released thanks to a mass campaign for amnesty.

In one of the first battles of the Rebel Army, in December 1956, Batista’s troops outnumbered the revolutionaries and yelled at them to surrender.

“No one surrenders here, damn it!” Almeida shouted back. That became a battle cry of the Rebel Army.

In February 1958 Almeida was promoted to commander, and Castro named him head of the newly formed Third Eastern Front in the Sierra Maestra mountains. After the revolutionary victory, Almeida served as head of the air force, vice minister of the Revolutionary Armed Forces, and vice president of the Council of State. He was also a member of the Cuban Communist Party’s Political Bureau.

Castro: ‘A privilege to know him’

In a Sept. 13, 2009, tribute to Almeida after his death, Fidel Castro wrote, “I had the privilege of knowing him — a young black militant worker who would become, successively, the leader of his revolutionary cell; a combatant at Moncada; a fellow prisoner; a platoon captain at the time of the Granma landing; an officer in the Rebel Army, prevented from advancing by a bullet in his chest during the violent battle of Uvero; the commander of a column that marched on to create the Third Eastern Front; and a compañero sharing the leadership of our forces in the final successful battles that overthrew the tyranny.

“I was an exceptional witness to his exemplary conduct for over half a century of heroic and victorious resistance: in the struggle against the bandits; the Girón [Bay of Pigs] counteroffensive; the October [1962] Missile Crisis; our internationalist missions; and the resistance to the imperialist blockade,” Castro said.

“He defended principles of justice that will be defended at all times and during all periods, as long as human beings breathe on Earth.”

At the meeting at Casa de África, most of those in the audience were revolutionary combatants themselves. During the discussion, a young man visiting from the United States asked them, “What does it mean to be a revolutionary for life, like Almeida was?”

The hands shot up in the air. One combatant after another gave an answer from his or her own experience.

Edgar Cordero, who grew up in a peasant family in capitalist Cuba, explained how, when he was a baby, his father once had to scrape money together to buy medicine to save his life. After the revolution, Cordero learned to read and write during the 1961 literacy campaign. He later joined Cuba’s volunteer mission in the Congo, responding to a call by the revolutionary government.

“At the moment I was called to go fight in Africa,” Cordero said, “my daughter was in the hospital in intensive care. I was given the choice to stay with her, but I decided to go. I told myself, ‘We made a revolution, and I know my daughter will be taken care of. The revolution needs me now in Africa.’ ”

Another member of the Combatants Association described how, as a teenager in 1961, she went to a remote mountainous area as part of the 270,000 volunteers who wiped out illiteracy in Cuba within a year.

Each of the combatants made the same point — how, in the course of participating in the revolution, they became different men and women.