Prison officials in Huntsville, Texas, executed 41-year-old death row inmate Ramiro Gonzales using a pentobarbital injection June 26. He had been sentenced to death in 2006 for the sexual assault and murder five years earlier of Bridget Townsend, the girlfriend of his drug dealer. Gonzales was 18 at the time of the killing, an addict who had been abandoned by his mother and only met his father later when they happened to be in the same prison.

The Texas Board of Pardons and Parole unanimously voted June 24 to deny a clemency petition that would have reduced Gonzales’ sentence to life in prison. The U.S. Supreme Court denied Gonzales’ appeal the day he was executed.

Numerous letters of support, videos and 20,000 protest signatures were submitted to the board. “Many painted a picture of Gonzales as a changed man who volunteered a kidney to a stranger; never committed another act of violence; became a preacher; and was appointed by prison administrators to serve as a mentor for other inmates,” wrote the Washington Post June 26.

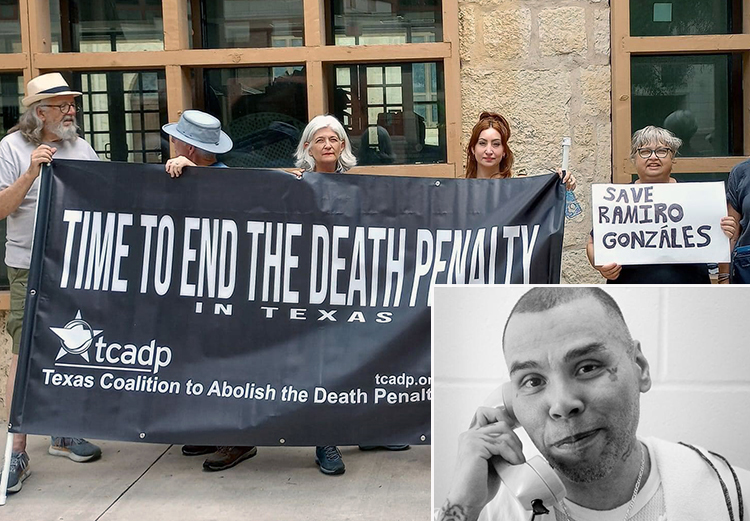

On the day he was put to death, rallies protesting the execution took place in Austin at the state Capitol and in front of the Huntsville penitentiary.

In addition to evidence of his rehabilitation, another key issue in Texas was a compelling argument for reducing Gonzales’ sentence. His attorneys pointed out that he should be ineligible for execution, providing evidence he posed no risk of “future dangerousness,” a criteria presented to juries for sentencing in Texas since 1973.

“Before imposing the death penalty, Texas requires jurors to consider the probability that the defendant ‘would constitute a continuing threat to society’ — a measure known as the ‘future dangerousness’ standard,” the Post explained.

In 2022, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals directed a lower court to review Gonzales’ claim that his death sentence resulted from false testimony by psychiatrist Edward Gripon, an “expert” for the state. He referred to a statement by Gonzales’ cellmate who later admitted he had been pressured to lie.

During the trial, Gripon relied on statistics about the likelihood of people who have committed a sex crime to do so again. In 2022 Gripon recanted his testimony, saying he had relied on a 1980s psychology magazine article written by someone without any credentials. As to Gonzales, who he had recently interviewed again, Gripon wrote, “I don’t think that diagnosis would now be accurate.”

Gonzales’ cellmate admitted he had made up his earlier testimony after a prison official threatened him with a harsher sentence if he didn’t do so.

In 1976 the Supreme Court had upheld using “future dangerousness” in sentencing hearings. But as early as 1982 the American Psychiatric Association concluded the “unreliability of psychiatric predictions of long-term future dangerousness is by now an established fact within the profession.”

“The reason why they bring in a psychiatrist who gives testimony on future dangerousness is for the sole purpose of sending you to death row,” said Gonzales. “His job is to make you look like the worst individual that anybody’s ever seen — a monster.” The capitalist rulers use the death penalty — and their whole criminal ‘justice’ system — not to rehabilitate workers behind bars, but to intimidate them and reinforce their predatory profit-driven system

In Gonzales’ last words before his execution he addressed the Townsend family. “I can’t put into words the pain I have caused you all, the hurt, what I took away that I cannot give back,” he said. “I lived the rest of this life for you guys to the best of my ability for restitution, restoration, and taking responsibility.”

Gonzales’ execution was the eighth in the U.S. so far this year. The ninth was Richard Norman Rojem Jr., who was executed in Oklahoma by a three-drug lethal injection the next day.