This month marks the 77th anniversary since thousands of survivors of the Holocaust boarded a ship in France, soon renamed Exodus 1947, in an attempt to rebuild their lives in Palestine. From the get-go the ship was trailed, then brutally attacked, by British naval forces and seized in international waters before reaching its destination.

Part of the story about this ship has been popularized in the 1960 film “Exodus,” based on a novel by Leon Uris. But neither the movie nor the book tells the true story of what happened.

London sought to halt Jewish immigration to Palestine, part of its colonial empire that it hoped to hang onto. Like its imperialist allies in the U.S. and Canada, the British rulers prevented Jews fleeing Nazi persecution before, during and after World War II from entering their country. Survivors of the Holocaust were housed in squalid displaced persons camps, some located in former Nazi concentration camps.

The ship, originally called the President Warfield, was a rickety old steamer. Originally designed to accommodate 400 passengers, it was purchased by Jews in the U.S. and refurbished to hold thousands.

Some 4,554 men, women and children — many traveling with false papers in over 170 trucks from the camps in Germany and Poland — climbed onto the cramped ship in Sete, France, July 11 to begin the trip.

Thirty-five of the 39 members of the ship’s crew were U.S. volunteers, most of them Jewish.

U.S. volunteer Bernie Marks snuck into the water and swam to the pier to loosen the ropes. Sailing at night in hopes of not being spotted, the ship took off with no lights showing and without the aid of a pilot or tug. It got stuck in the mud, but managed to pull free and get out to the Mediterranean.

But it had been spotted by a British spy plane, and followed by a British armada fleet that grew to 12 ships, including three destroyers and a cruiser, as the Exodus neared the coast of Haifa in Palestine.

“The British, apparently, hadn’t bothered to wait until we crossed the boundary into territorial waters, but had attacked us on the high seas,” wrote Dov Freiberg, a passenger on the Exodus. “It was true, that one way or another we weren’t going to win the battle, but not for one moment had the thought entered our minds to surrender.”

Attacked, imprisoned by the British

British forces fired tear gas and machine-gunned the passengers. Two destroyers rammed the fragile ship from opposite sides, smashing into its upper decks and threatening to sink it. Armed British sailors stormed on board.

“We were fighting them with sticks and bare fists. Face-to-face and hand-to-hand fights were taking place the whole length of the deck,” Freiberg said.

The British clubbed to death the first mate, William Bernstein, 24, a U.S. Jew. Two passengers were killed, Mordechai Bunstein, 23, a concentration camp survivor, and Hirsh Yacubovitch, 15, who survived the Nazis in Poland. Dozens of others were wounded.

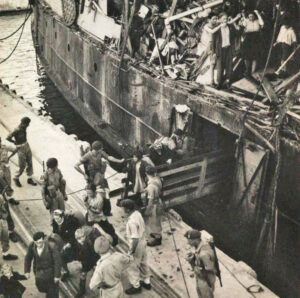

After three hours of fighting, the British navy towed the Exodus into Haifa harbor. It was met by a crowd of several thousand Jews demonstrating their solidarity with the embattled Jewish passengers. British officials forced all the passengers to disembark, ran them through delousing, and reloaded them on three navy transports — Runnymede Park, Ocean Vigour and Empire Valour — that had been refitted into caged prison ships. Among those on the scene to speak with the Jewish refugees, looking to expose the horrendous conditions they faced, was Ruth Gruber. She was one of only three journalists allowed aboard the prison ships, and the only one to bring a camera.

“I took countless picture of them,” she told the New York Times in a 2011 interview. “Nobody could destroy them. They survived the death camps, the D.P. camps, the broken-down ship and now this ship.”

As she left the ship, the British consul-general demanded she turn over her film. Gruber refused. British authorities then told her, as they told the Exodus veterans, the ship would be landing at the British D.P. camp in Cyprus. Gruber flew there to meet them, but the British had lied.

The three prison ships sailed back to France. Conditions on board were horrendous with refugees crammed together. But upon arrival in Toulon, the passengers refused to disembark for three weeks, many conducting a 24-day hunger strike. French authorities refused British demands to forcibly remove them.

Forced back to Germany

British authorities then sailed the ships to Hamburg in the British-occupied zone of Germany. There, on Sept. 8 in front of the eyes of the international press, most of the Jewish refugees were forcibly dragged from the ships by 2,500 British marines. “They charged us and began hitting us with clubs and truncheons on the heads and arms,” wrote Freiberg.

They were taken to displaced persons camps in Poppendorf and Am Stau. “Our arrest camp resembled from the outside a German concentration camp,” Frieberg said, describing his incarceration in Poppendorf. “Armed soldiers guarded us night and day.”

The United Nations voted on Nov. 29, 1947, to divide Britain’s expiring mandate over Palestine into two new states, Israel and Palestine. The U.S. rulers, looking to replace Britain as the dominant imperialist power in the Middle East, backed Israel’s statehood. When Britain’s mandate ran out, Israel declared its statehood May 14, 1948.

The embattled Exodus refugees, who had no other option, made their way to a new life in Israel.

“4,500 Jews Get Another Lesson in ‘Democracy,’” headlined an Aug. 4, 1947, article in the Militant about the Exodus’ journey. “The British imperialist brigands are not alone in their responsibility for this monstrous episode which is only one of the shocking crimes against a long-suffering people,” it said. This “cannot cover up the crime of Wall Street’s government in closing the doors of this country to these displaced persons.”