A month after Ukrainian forces drove into the Kursk region of Russia Aug. 6, opposition to the war is growing among Russian conscripts and their families. The Ukrainian offensive is aimed at dealing blows to Moscow’s invasion led by Russian President Vladimir Putin that aims to wipe out Ukraine’s independence and conquer its people.

Unlike Ukrainian working people volunteering to fight to defend their country’s sovereignty, there is little patriotic fervor among working people in Kursk.

When Kyiv’s forces swept across the lightly protected Kursk border, they overpowered Russian conscript soldiers there. Hundreds surrendered and were taken as prisoners of war.

The Ukrainian government allowed the Moscow Times to interview several captive Russian conscripts, whose names were withheld for their protection. All wanted to return home, but said their experiences have led them to see through the lies Moscow tells about its invasion.

One conscript from Moscow said he was glad they were able “to get through the war alive.” When he gets home, he wants to make sure “a war like this never happens again.” He added, “I’m not going to die for these bastards. I don’t owe Russia anything.”

“We heard that they [the Ukrainians] torture, torture, torture. But in reality, it turned out to be different,” another captured conscript said. “We feel good here.”

“They feed us three times a day. We have a place to sleep,” another said. “We have a kitchen. We have everything we need for our lives.”

A conscript from Bryansk said that his platoon was ordered to fight to the last man. Instead, the 11 young men surrendered without any problems.

Another from St. Petersburg is receiving full medical treatment for his injured legs. Scared about what would happen after his capture, he tried to blow himself up with a grenade. When the war eventually ends, “the guys in the Kremlin will sit down with serious faces and say we have achieved peace,” he said. “Go to hell, guys!”

All Russian men aged between 18 and 30 are required to serve in the army for a year. Unlike contract soldiers paid and drilled for combat, they lack training and experience. Early in the invasion of Ukraine, conscripts were sent to the frontlines despite Putin’s promise that they would not be deployed there. This led to an angry response from their mothers and wives.

Moscow reacted by transferring conscripts to guard Russia’s border regions, seemingly far from the conflict. Now that has backfired, with families furious over their loved ones being killed or captured. Thousands have signed online protest petitions against the use of conscripts there.

The comments of the conscripts and protests by their families underscore the fact that working people in Russia are the most important allies of Ukrainians fighting to defend their country.

Moscow’s costly advances in east

Putin claimed Sept. 2 that Kyiv’s plan “to stop our offensive actions in key parts of the Donbas” by forcing the diversion of Russian troops to fight inside Russia has failed. Ukrainian forces now control over 500 square miles of territory in Russia’s west. Kyiv’s forces have been slowed but not stopped by extra troops Moscow has sent to Kursk from African deployments and elsewhere.

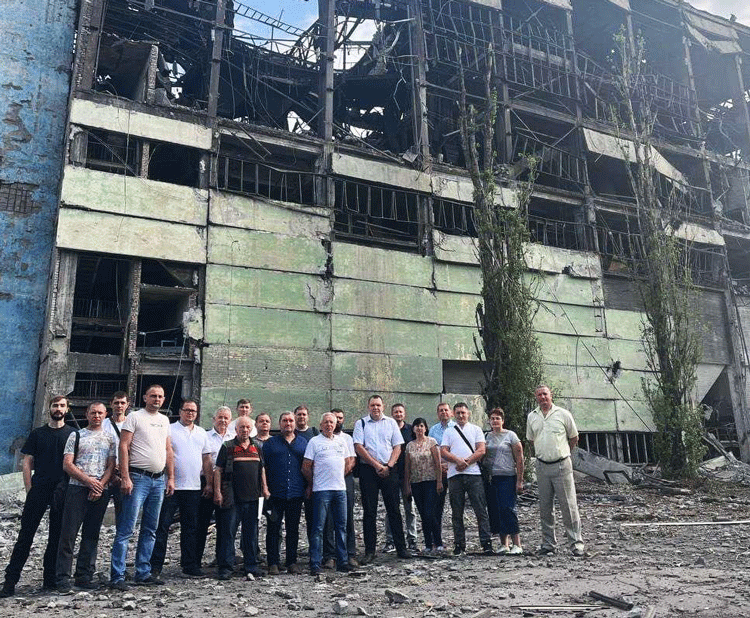

In response to the Ukrainian counteroffensive, Putin’s regime is stepping up its bombardment of Ukrainian cities. In the deadliest airstrike so far this year, Moscow hit Poltava in central Ukraine Sept. 3, killing 51 people and injuring 271.

On Ukraine’s southeastern front, Moscow’s forces were within 6 miles of Pokrovsk. The city is a coal mining and rail hub that supplies Ukraine’s military. Once home to 80,000, it is being evacuated.

Ruslan, 42, a former miner and now a commander of Ukrainian forces defending the frontlines around the city, described how Russian troops march forward as their fellow soldiers are mown down around them. “This is just waves of meat,” he told the Washington Post, pointing to the Kremlin’s utter contempt for the lives of the workers and farmers who serve in its armed forces.

“When we push [the Russian invaders] out, we will come back,” Volodymyr Porosyuk told the New York Times as he left the city with his grandmother.

The coal mine, the city’s biggest employer and a supplier for the country’s industry, now runs with just over half the 8,000 workers it had before the war. Miner Oleksandr Dichko explained that miners also work to bolster the city’s defenses. “You come to work, clock in, and then you receive the call to go dig [trenches],” he told the Wall Street Journal. Like at other mines, dozens of women work there now, as men leave for the front.

An Aug. 26 statement by the Confederation of Free Trade Unions of Ukraine (KVPU) denounced deadly missile attacks by Moscow on workers, members of the KVPU and residents across 15 regions of Ukraine. The targets included mines and energy infrastructure.

The union appeal for solidarity said: “Ukrainian workers, members of trade unions, continue to work despite the danger and are also fighting the Russian occupiers on the front lines.”