The French edition of Malcolm X, Black Liberation, and the Road to Workers Power by Jack Barnes is one of Pathfinder’s Books of the Month for September. Below is an excerpt from a talk by Barnes, national secretary of the Socialist Workers Party, at a March 28, 1987, meeting in Atlanta. It appears in the book as, “Malcolm X: Revolutionary Leader of the Working Class.” Copyright © 2009 by Pathfinder Press. Reprinted by permission.

We need to understand and absorb Malcolm’s political legacy because it’s a powerful political tool we must have to help make a socialist revolution in the United States. It aids us in gathering and unifying the forces among working people and youth who will forge a working-class party able to lead such a revolution. It is needed by anyone, here or anywhere else on earth, who wants to be part of an international revolutionary movement of the kind Malcolm was so determined to help build — a movement to rid humanity of all forms of oppression and exploitation. …

Malcolm X emerged on American soil as the most representative revolutionary leader with a mass hearing in the latter half of the twentieth century. He converged politically with other revolutionists the world over, including proletarian revolutionists, communists, here in the United States. He was going in the direction the world revolution was going, against colonialism and capitalism, and with those who were pushing revolutionary struggle forward. Many individuals, in many countries, who aspire to lead revolutions on their home turf are still catching up with Malcolm on many fronts.

Malcolm’s course during these final months is sometimes described as a new form of Pan-Africanism, and Malcolm himself used that term a few times. But “Pan-Africanism” captures neither the scope nor the revolutionary political character of Malcolm’s internationalism and anti-imperialism. Malcolm, of course, recognized the shared aspects of the oppression facing those of African origin — and of their resistance to that oppression. Because of the combined legacy of colonialism and chattel slavery, Blacks shared many such elements whether they lived and toiled in Africa itself, in the Caribbean and Latin America, in Europe, or what Malcolm, echoing Elijah Muhammad’s marvelous term, called “this wilderness of North America.”

“Many of us fool ourselves into thinking of Afro-Americans as those only who are here in the United States,” Malcolm said in one of his last talks, just five days before he was assassinated. “But the Afro-American is that large number of people in the Western Hemisphere, from the southernmost tip of South America to the northernmost tip of North America, all of whom have a common heritage and have a common origin when you go back to the history of these people. … [And when Africans] migrate to England, they pose a problem for the English. And when they migrate to France, they pose a problem for the French.”

At the same time, Malcolm increasingly identified with, championed, and explained revolutionary struggles the world over — from the Chinese Revolution, to the Cuban Revolution, to battles for national liberation wherever they were being fought, and by people of whatever hue of skin color.

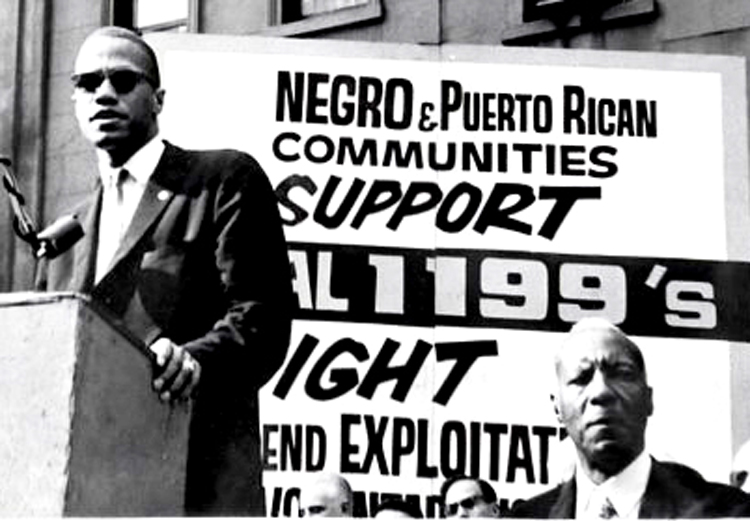

At this meeting tonight, however, I want to try to make the case that is perhaps the most important of all, not just for revolutionists in this country but those around the world. I want to make the case that Malcolm X was a revolutionary leader of the working class in the United States.

That may sound strange, for a number of reasons. It may sound strange because of the small degree of support Malcolm had among workers who were Caucasian, at least those he knew of. It may sound strange because of the weakened state of the labor movement and procapitalist positions of the union officialdom that I described earlier, views that were diametrically opposed to Malcolm’s. It may sound strange, if for no other reason than that Malcolm himself never directly addressed this question.

But the fact remains that the social and political transformations that will be wrought by a popular revolution in the United States — a revolution that will be led by the vanguard of the working class, or else go down to a bloody defeat — are decisive for the oppressed and exploited the world over. Among other things, the conquest of power by the working class and its allies — the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat — is the necessary step that can open the road for Blacks, and for all supporters of Black rights, to successfully fight to end racist oppression of every kind once and for all.

In the leadership of revolutionary working-class struggles in this country, workers who are Black will occupy a vanguard place and weight disproportionate to their numbers in the U.S. population. That’s what all modern history teaches us. That fact is testified to by the record of powerful social and political struggles in the United States: from battles during the closing years of the Civil War itself; to Radical Reconstruction and the efforts to prevent the imposition of peonage among the freed slaves; to the struggles that built farmers movements and the industrial unions in the 1920s and 1930s; to the mass proletarian movement that toppled Jim Crow segregation, fueled the rise of greater political self-confidence and nationalist consciousness among Blacks in the 1960s, and inspired what became the mass movement against the imperialist war in Vietnam.

Malcolm X was a legitimate political heir to all these struggles.

But who are Malcolm’s heirs? …

[T]he heirs of Malcolm X will come forward — all over the world, including right here in the United States — as revolutionary struggles advance, as the exploited and oppressed organize to resist the devastating consequences of capitalist crises and imperialist domination and wars. More leaders like Malcolm will come forward, including in the labor movement. And they will need to know who Malcolm was, what Malcolm stood for, what he fought for and dedicated his life to.