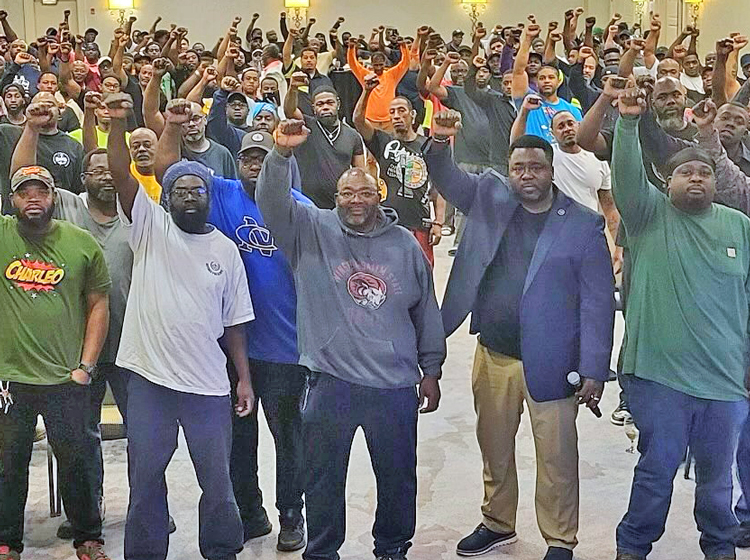

The Oct. 1 strike deadline for 45,000 dockworkers on the East and Gulf coasts is rapidly approaching, with members of the International Longshoremen’s Association at three dozen ports from Texas to Maine organizing to walk out if no new contract is in place. Hundreds packed union meetings around the country over the past two weeks to discuss strike plans. It would be the union’s first walkout since 1977.

Wages are one of the key issues. “The ILA proposal not only makes up for the past few years of extremely high inflation, and long-term inflation going back decades,” ILA President Harold J. Daggett told a meeting of 250 union delegates in Teaneck, New Jersey, Sept. 18, but “also ensures the financial security of ILA members and their families through the uncertainty of the coming years.”

On Sept. 23 the union said the two parties had been in communication many times in recent weeks but a stalemate remains. The employers’ group, the United States Maritime Alliance, “continues to offer ILA longshore workers an unacceptable wage increase package.”

The bosses’ push for more automation is the other critical issue, both to prevent job losses and defend safety on the job. Negotiations broke down June 10 when ILA officials said they discovered automated equipment to process trucks was being used at Alabama’s Port of Mobile, in violation of the current contract.

Working on the docks is dangerous. On Sept. 18 a worker died at the Port of Houston after a stack of pipes collapsed onto him. A report published in February by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health says workers in marine terminals and port operations are five times more likely to die on the job than other workers.

The threats to workers’ health from automation caused bosses at the Port of Auckland in New Zealand, after spending $65 million, to back off moves toward automation in 2021. As one news article put it, the signs of trouble were not subtle: “When large machines which are supposed to be coordinated crash into containers and topple over walls, you know something is seriously wrong.”

The ILA has also had to fight attempts by bosses to open new marine terminals without union representation. After two ocean carriers attempted to unload with nonunion labor at the new Leatherman Terminal in the South Carolina Port of Charleston in 2021, the ILA took them to court, finally winning its case this year. One group deeply disappointed by the decision was the bosses planning a similar nonunion scheme for a new container terminal in Georgia’s Port of Savannah.

A group of 177 retailers, manufacturers and automakers have sent a letter to the White House demanding that the Biden administration step in to stop any strike. The strike at this point “would have a devastating impact on the economy,” they said. East and Gulf coast ports handle more than 40% of U.S. imports.

The shipping carriers, never passing up an opportunity, have already announced plans to hike rates.

So far President Joseph Biden says he won’t interfere. “We’ve never invoked Taft-Hartley to break a strike and are not considering doing so now,” a Biden administration official told Reuters. Time will tell, but it’s worth recalling that Biden, backed by a bipartisan Congress, invoked the notorious Railway Labor Act to force rail workers back on the job in 2022 under a contract they had voted down.

Fighting government interference

Dockworkers have long experience with government interference, from threats to invoke the Taft-Hartley Act, to restrictions on pickets, to attacks by the courts and cops. Nowhere is this better known than at the Port of New York-New Jersey, where the infamous Waterfront Commission regularly busted labor actions and framed union militants, claiming the union was controlled by “the mafia.”

The 70-year-old Commission of New York Harbor officially closed shop in July 2023. New Jersey officials won a U.S. Supreme Court decision holding that since the harbor’s working docks are now 90% in New Jersey, and the New Jersey State Police was more than capable of licensing dockworkers and policing the port, the commission should be disbanded.

In April, New York authorized a new Waterfront Commission to hold sway over the remaining New York docks. This decision was praised by New York’s Daily News Sept. 3, which claimed the New Jersey legislature had bowed to “Harold Daggett and his mobbed-up International Longshoremen’s Association.”

The FNV Havens union, the largest union of longshore workers in the Netherlands, told the U.S. union that it “fully supports the ILA in their just demands for fairness. Port workers often serve the same shipping companies worldwide,” it said, that “make mega profits and believe they can demand anything and everything from port workers.”

Statements of support have also come from the International Longshore and Warehouse Union, whose members work on the West Coast; Bermuda Industrial Union; International Transport Workers Federation, which represents 20 million transportation workers globally; and the International Dockworkers Council, which represents 120,000 dockworkers.