![]() Below are the first two chapters of the new 2024 edition of Cosmetics, Fashion, and the Exploitation of Women by Mary-Alice Waters, Evelyn Reed and Joseph Hansen, available in December. Waters is a longtime leader of the Socialist Workers Party and president of Pathfinder Press. In the last issue, the Militant printed Waters’ preface.

Below are the first two chapters of the new 2024 edition of Cosmetics, Fashion, and the Exploitation of Women by Mary-Alice Waters, Evelyn Reed and Joseph Hansen, available in December. Waters is a longtime leader of the Socialist Workers Party and president of Pathfinder Press. In the last issue, the Militant printed Waters’ preface.

The two chapters are “Norms of Beauty and Fashion Are Inseparable from the Class Struggle,” by Waters, and “As Though It Were Written Today,” remarks by Isabel Moya at the presentation of the Cuban edition of Los cosméticos, las modas y la explotación de la mujer at the Havana International Book Fair Feb. 14, 2011. Moya was a leader of the Federation of Cuban Women and director of its publishing house Editorial de la Mujer.

Copyright © 2024 by Pathfinder Press. Reprinted by permission.

Beauty has no identity with fashion. But it has an identity with labor. Apart from

the realm of nature, all that is beautiful has been produced in labor and by laborers.

EVELYN REED

In the early 1950s a revolutionary socialist newsweekly based in New York — one whose masthead proudly proclaims that it is “published in the interests of working people” — ran a humorous, if at the same time serious, exposé of plans by the cosmetics arm of the “fashion industry” to conspire once again to bolster sales and increase profit margins. It was capitalist business as usual, the Militant reported in 1954.

The merchants of “beauty” were ramping up another advertising campaign, aimed at convincing working women they simply had to have a new line of products in order to be happy, secure, employable, and sexually desirable.

A few readers of the paper responded with angry letters to Militant editor Joseph Hansen, attacking the author of the exposé, Jack Bustelo. They accused Bustelo of ridiculing working-class women and attacking their “right” to strive for “some loveliness and beauty in their lives.” It turned out that “Bustelo,” the brand name of a dark-roast coffee popular in New York City among Puerto Ricans and Cubans, and much liked by the paper’s editor, was the pen name under which Hansen himself had drafted the article.

The lively polemic that ensued — first in exchanges carried by the Militant and then continued in a discussion bulletin for members of the Socialist Workers Party — became a textbook in the fundamentals of Marxism. Hansen’s article “The Fetish of Cosmetics,” originally published in the bulletin, provided a popular introduction to Karl Marx’s Capital, the most comprehensive critique of political economy ever written. Hansen rendered the seeming mystery of “commodity fetishism” understandable to the newest reader.

In clear and pedagogical responses to Bustelo’s critics, SWP leader Evelyn Reed joined the debate. She explained that norms of beauty and fashion are, above all, class questions and cannot be separated from the history of the class struggle. She explained how and why ever-changing standards of “beauty” and “fashion” imposed on women — and men — are integral to the perpetuation of women’s oppression. How millennia ago, as the productivity of human labor grew at an accelerating rate, private property and class society emerged in the course of bloody struggles, and women were reduced to a form of property. They became the “second sex.”

“Millennia ago, as labor

productivity accelerated, class

society arose from bloody

struggles. Women were reduced

to a form of property . . .”

Today the fight to eradicate women’s subordinate status is not simply a “woman question,” Reed explained. It is an integral part of the working-class struggle to take state power out of the hands of the families that dominate large-scale industry, banking, and trade. Only that historic step forward for humanity can open the door to women’s equality through ending all forms of exploitation and oppression, as well as the increasing threat of worldwide imperialist war and nuclear catastrophe.

Hansen’s opponents in the “Bustelo controversy,” as the polemic became known in the ranks of the SWP, found fertile ground in the relative prosperity and working-class retreat that marked the post–World War II years in the United States. The early 1950s, often referred to as the McCarthy period, were characterized above all by the emboldened offensive mounted by the capitalist rulers to housebreak militant sections of the trade union movement that had emerged from the labor battles of the 1930s and mid-1940s. Women — and African Americans — who had joined the industrial workforce by the millions during the capitalists’ wartime labor shortage were pushed back and down.

Within a few short years after the Bustelo affair, however, that political landscape changed dramatically.

The 1959 victory of the Cuban Revolution brought renewed proof of the capacity of ordinary working people to take state power and begin transforming the world they inherited. It provided unimpeachable evidence, moreover, of the vulnerability of the US rulers.

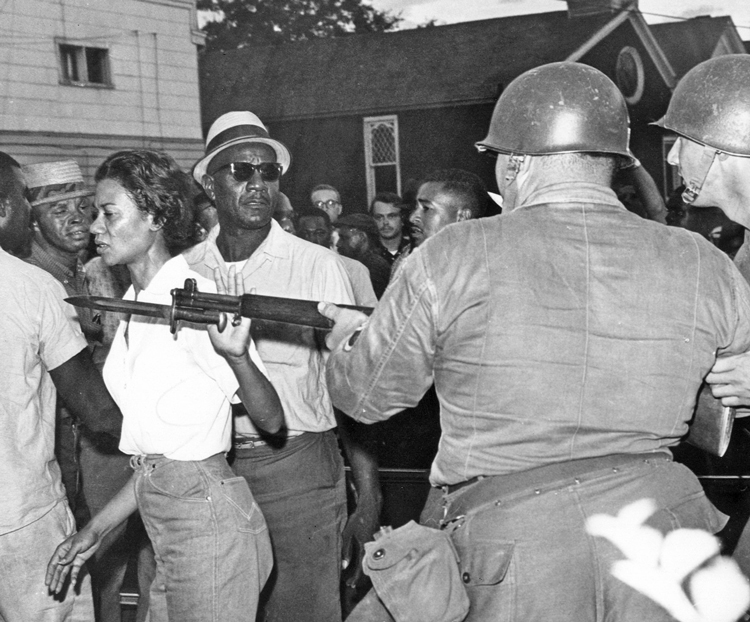

In the United States, a broad political radicalization accelerated in the 1960s, propelled above all by the victorious class battles, spearheaded by African American workers in the major industrial cities of the South, that brought down the system of Jim Crow racial segregation. The American model for “apartheid,” a model that had been in place for the better part of a century, was uprooted. Race relations in the US were changed forever. Known more broadly as the civil rights movement, that historic struggle awakened millions of all races, including new generations of young people, to political life.

The high point of the civil rights movement intersected with Washington’s expanding war against the Vietnamese people fighting for the national sovereignty and unification of their country. Hundreds of thousands of youth — Black, Caucasian, Puerto Rican, Native American, Mexican American, Asian American — conscripted to fight and die in that war saw with their own eyes the true face of US imperialism. Some 58,000 Americans and an estimated three million Vietnamese lost their lives in Washington’s imperialist adventure, before Vietnam’s liberation fighters emerged victorious. Many US soldiers came home to join millions across the country and the world demanding “Bring the troops home now!”

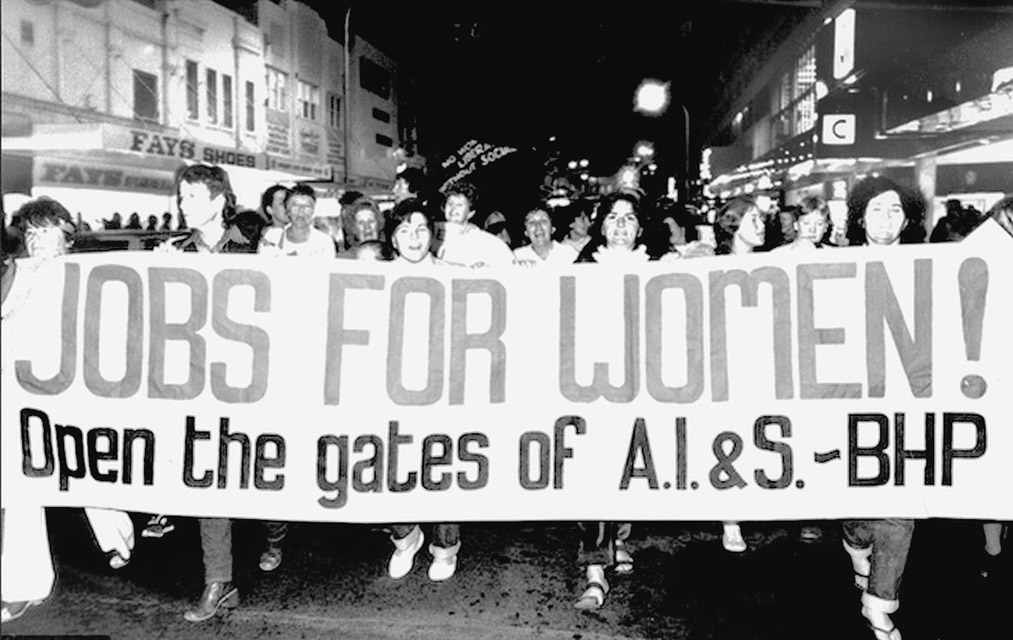

An integral part of this deepening politicization and radicalization was the birth of a new wave of struggles against the millennia-long oppression of women as the “second sex.” Women took to the streets. Along with their allies, they demanded equal pay for equal work, the expansion of childcare facilities, an end to involuntary sterilizations, and above all, the repeal of every law criminalizing abortion.

And, as during the civil rights movement and anti–Vietnam War movement, many often displayed a good dose of both liberalism and ultraleftism as they began organizing.

This “second wave” of the modern fight by women to cast off the shackles of their second-class status exploded in the 1970s and began to spread internationally. As it did so, the exchange of letters and articles that were part of the “cosmetics debate” became a powerful educational tool, one that was often in demand.

“The civil rights movement

awakened millions of all races

to political life. It inspired new

struggles against oppression of

women as the ‘second sex’ . . .”

Dog-eared copies of the mimeographed SWP Discussion Bulletin containing the materials published here as Cosmetics, Fashion, and the Exploitation of Women passed from hand to hand among hundreds, even thousands, of young women — and men — who were searching for explanations of women’s oppression and how to fight to end it.

The uncompromisingly historical materialist approach and working-class perspective they found there helped many to become communists — or better, more conscious communists. It helped them understand that the fight to end women’s oppression is inseparable from the political struggle to replace the dictatorship of capital and its universal fetishism of commodities with the state power of the working class.

And with it, the eradication of capitalist property relations.

* * *

The “cosmetics debate” entered its third life in 1986 when it was published for the first time as a book. By then the post–World War II rate of expansion of production and trade had slowed. The rising living standard won by the US working class in the postwar years came under increasing attack as the capitalists’ rate of profit declined worldwide. The roots of the long, grinding capitalist crisis that has marked the last decades had begun to manifest themselves. Many gains for women won by battles in the 1960s and ’70s came under assault by the employers and their government.

In the US access to medically safe, legal reproductive health services, including abortion — a precondition of women’s emancipation — was again being curtailed, state by state.

Affirmative-action programs initiated in the 1970s by the United Steelworkers and a few other trade unions to reduce race divisions within the working class were beginning to be rolled back by the employers. What’s more, programs claiming to promote such equality were turned into their opposite by middle-class layers seeking their own self-advancement. “Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion,” as it became known, blossomed well beyond the elite campuses where it was born. It became a source of executive, professional, and academic perks for an upper-middle-class layer of women — and men — of all skin colors. Unlike the affirmative action fought for by the labor movement, “DEI” served only to sharpen divisions of race and class.

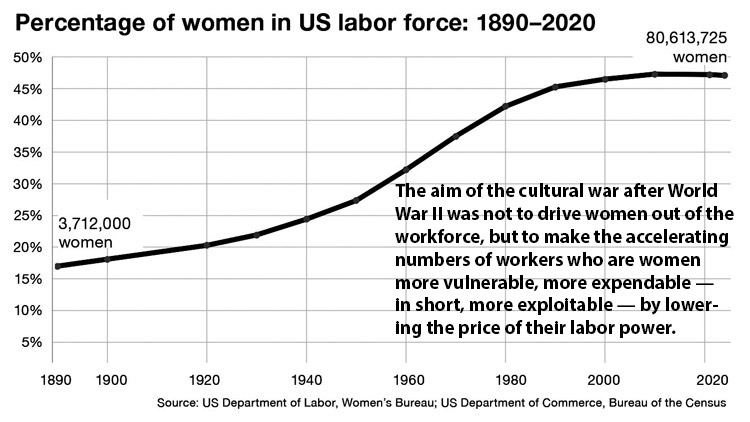

An ideological campaign — a “culture war” against working women — was mounted by the capitalist rulers and their privileged spokespeople. The target was the tens of millions of women who had entered the labor market in unprecedented numbers during and after World War II, especially those who had led the way into occupations previously considered male preserves.

The purpose of this political campaign was not to drive women out of the workforce. To the contrary. The aim was to make the growing numbers of workers who are women more vulnerable, more expendable — in short, more exploitable — by lowering the price of their labor power and thus slowing the pace at which the bosses’ profit rates were declining.

The mass media that serves the interests of capital (“social media,” serving the same class interests, had not yet been devised) was full of articles seeking to convince readers that advances by women in job opportunities and pay are unfair to men, especially men who are Black. That job exclusions and wage differentials between men and women are justified. That they are to be expected. After all, biology is woman’s destiny, and her primary social responsibility and source of “fulfillment” is motherhood. Hearth and home is not only where she belongs, but the only place she can ever belong.

In face of this concerted counteroffensive against women’s greater social equality, the diverse class forces that had comprised the rising women’s liberation movement in the 1970s fractured. It was a rout that mirrored the retreat that was happening in the organized labor movement.

When published in 1986, Cosmetics, Fashion, and the Exploitation of Women placed these mounting pressures in a broader class and historical framework. It opened — and still opens — a window onto the post–World War II decade, when a similar economic, political, and ideological offensive was pressed by the class whose wealth comes from the exploitation of our labor.

That earlier political offensive was broadly promoted as the “feminine mystique.” It was designed to convince women who had joined the workforce by the millions during the labor shortages of World War II that they were solely “homemakers” who should sell their “attractiveness” — not workers, who could sell their labor power.

The broader political perspective found in these pages helps clarify what was again bearing down on even the most politically conscious women and men in the closing decades of the twentieth century. It helps explain why the “women’s movement” of the 1970s had become thoroughly bourgeoisified, little more than an electoral appendage of the capitalist class, especially the Democratic Party.

***

Each day’s news accounts bring home to us ever more sharply that we are today living through the opening of what will be years of worldwide economic, financial, and social convulsions, class battles, and wars. The opening guns of World War III are already being heard, but the unimaginable is not yet inevitable.

That depends on which class rules. The international working class is today far larger and potentially more powerful than in the years that preceded the two interimperialist slaughters of the twentieth century.

What’s missing is growing working-class consciousness that can — and will — develop only in the course of struggle.

What’s missing is trusted, battle-tested, genuinely communist — not Stalinist — leadership, leadership of the kind provided by V.I. Lenin and the Bolshevik Party he forged in the tsarist empire. Leadership of the kind exemplified by Fidel Castro and the cadres of the July 26 Movement and above all the Rebel Army in Cuba, who opened the door to the first socialist revolution in the Americas.

What’s missing is leadership of the exploited producers of all skin colors and nationalities like that demonstrated by Malcolm X in the final years of his life, a leadership with moral courage and integrity.

And those kinds of leadership, too, can only be forged in the heat of class battles.

This is the world context in which the qualitative increase over the last century in the percentage of women taking part in the international workforce is a vital factor. Women will shoulder greater leadership responsibilities than ever in the revolutionary, working-class-based battles to come.

With this new edition, Cosmetics, Fashion, and the Exploitation of Women has begun its fourth life — and not a moment too soon.

* * *

Two questions asked by thoughtful readers since the initial publication of Cosmetics, Fashion, and the Exploitation of Women are useful to consider.

First, are the issues addressed in a debate about cosmetics and fashion many decades ago still relevant? Aren’t they long bypassed?

Second, isn’t Reed’s article on “Anthropology: Marxist or Bourgeois?” outdated? Hasn’t knowledge of the earliest human societies moved far beyond what was known in the mid-1950s?

The response to the first question is underscored by Hansen’s rhetorical question in “The Fetish of Cosmetics.” In the whole history of capitalism, Hansen asks, “has the bourgeoisie ever gone about cultivating the fetish of commodities more cold-bloodedly than American big business?”

It’s worth recalling that the birth of industrial capitalism itself was based on the production of textiles, wiping out domestic labor by women on home spinning wheels, looms, and sewing. One of the earliest promoters of the lucrative rewards to be had from the textile trade was a speculator and economist named Nicholas Barbon, cited a number of times by Marx in Capital.

“As capitalism heads into more

social convulsions and wars,

the outcome will be decided by

fights for workers power and

socialism worldwide . . .”

All across Asia and much of Europe, Barbon noted in 1690, apparel “is fixed and certain.” While in England and France “dress alters. Fashion or the alteration of dress is a great promoter of trade,” he observed. “Because it occasions expenditure for clothing before the old ones are worn out….

“It is the spirit and life of trade.”

More than three centuries later, the resources devoted by capitalist enterprises to advertising and the creation of markets — that is, creating “needs” where none yet exist — are still expanding astronomically. Under the profit system, instead of advances in the productivity of social labor breaking down this mystical animation of objects that working people ourselves have made, the working class and lower middle classes are pushed into “needing” more and more things. Everything from each new cell phone release, to the latest model automobile, $500 torn blue jeans, and an exploding array of “cosmetic” surgeries, skin bleaches or tanning salons, designer handbags, and cosmetics-designed-to-make-you-look-like-you’re-not-using-cosmetics.

All these and more are pushed on hapless “consumers” — even younger and younger children! — without pause.

The pressure to be “fashionable” — that is, to be “employable,” and attractive to a potential mate — has penetrated even more deeply into the working class. Under bourgeois domination, the internet and the misnamed “social media” have become new and more grotesquely powerful tools by which capitalist ideology, morals, and commodities intrude into our lives every minute of the day. And now looms “artificial intelligence” at the service of capital.

The manufactured compulsion to “shop” — playing above all on the emotional insecurities of women and adolescents created by capitalist social relations — has only deepened and spread. The “marketing” Hansen pokes such fun at in the 1950s seems amateur compared to the sales methods deployed against us today. “Shop until you drop” has gone from being a humorous exaggeration to a description of an actual social condition pushing increasing numbers of working-class families into more and more debt, often at usurious rates.

The impact of the twenty-first century capitalist advertising “industry” is, if anything, even more insidious as it spreads into areas of the globe previously buffered to some extent from the imperialist world market. In large areas of Africa, Asia, and Latin America, marked by imperialist-enforced agricultural and industrial underdevelopment, as well as in countries previously part of the now-defunct economic and trading bloc once dominated by the Soviet Union, the siren song of the commodity fetish is an imperialist weapon like none other.

What’s more, the “cosmetic surgery industry” penetrates more and more deeply into these countries as opportunities for socially useful production are squeezed out by competition from stronger capitalist powers.

“As their share of the workforce

multiplies, women will shoulder

more leadership in revolutionary

working-class battles . . .”

In the eloquent words of the Communist Manifesto, “the cheap prices of its commodities are the heavy artillery with which [the bourgeoisie] batters down all Chinese walls. . . . It compels all nations, on pain of extinction, to adopt the bourgeois mode of production; it compels them to introduce what it calls civilization into their midst, i.e., to become bourgeois themselves. In one word, it creates a world after its own image.”

As the not-so-outdated polemic of the 1950s makes clear, in periods of working-class retreat such as we’ve lived through for the last decades — a period of retreat far longer and more devastating than the relatively brief post–World War II years described in these pages — the “heavy artillery” of capitalism takes its toll, including among the most politically conscious layers.

* * *

The answer to the second question is equally important.

The articles by Evelyn Reed — “The Woman Question and the Marxist Method” and “Anthropology: Marxist or Bourgeois?” — are two of the earliest she wrote on these subjects. They were, in effect, “first drafts” of work that she continued to edit, expand, write about, and speak on for another twenty-five years. This edition of Cosmetics, Fashion, and the Exploitation of Women, in fact, incorporates Reed’s editing on “The Woman Question and the Marxist Method” when she prepared portions of it in 1969 for inclusion in Problems of Women’s Liberation, That title, along with Sexism and Science, Is Biology Woman’s Destiny?, and Reed’s widely acclaimed book Woman’s Evolution, all initially published by Pathfinder Press, have appeared in editions around the world in more than a dozen languages.

The focus of the sharp polemic in Cosmetics, Fashion, and the Exploitation of Women is what Reed often referred to as the “Hundred-Year War in Anthropology.” Here, as elsewhere, Reed defends the historical materialism of nineteenth-century anthropologist Lewis Morgan, whose work Karl Marx and Frederick Engels drew on extensively in their writings on the subject, as well as Morgan’s twentieth-century continuator Robert Briffault.

As Reed points out, one of the major battle lines in this century-plus war over historical materialism has been the question, Does something akin to the modern bourgeois “patriarchal system of marriage and family relations [go] all the way back to the animal kingdom?” Or did what is often referred to as the “patriarchy,” and the second-class status of women, arise in much more recent millennia as a cornerstone of class-divided societies?

Here as in her other writings, Reed answers these questions in clear, understandable terms. As agriculture and animal husbandry were developed, and the productivity of human labor increased, a surplus of food beyond that needed for mere survival began to accumulate. Over time this surplus was appropriated by a few — priests, tribal leaders, warrior chiefs — who were charged with guarding the communal reserves until needed. From such origins private property and all its class institutions eventually emerged and came to dominate all social relations, including relations between men and women.

Repeated many times and in different ways all over the globe, small numbers of men began emerging for the first time as a ruling class. In bloody conflict, they subjugated other men. Along with cattle and other domesticated animals, women and their children became valuable private property, the producers of new labor to be exploited. Familia, the Latin root of the term “family,” meant “a man and his slaves.”

“Concealed behind the debate,” Reed explains, is “a question of class struggle and class ideology.”

If class society and the accompanying subordinate status of women are only a stage of human history, one that arose at a certain historical juncture for specific reasons, then it can be eliminated at another historical juncture for other specific reasons.

If there has been an evolution of social relations through distinct stages of the prehistory and history of human society, determined by increasing levels of labor productivity and changing property relations — accompanied by enormous, and extended, conflict and violence — then capitalism and capitalist rule are no more permanent than the different property and social relations that preceded them.

Those studying and writing today about the development of social labor and the earliest stages of social organization are able to draw on a larger and richer body of research than the earliest anthropologists, or even those of Reed’s generation. Of that there is no doubt. Light will continue to be shed on the complexities, contradictions, and variety of human social evolution. But as Reed points out, recognition of diversity “is no substitute for probing into social history and explaining the evolution of human society as it advanced through the ages.”

There is no merit whatsoever to the argument that since different forms of marriage are found in the relics of primitive groups the world over, then “all you have to do is pay your money and take your choice,” Reed explains. That’s like saying “that because there are still relics today of feudalistic and even slave class relations, there was no historical sequence of human societies based on slavery, feudalism, and capitalism; that all we have is merely a ‘diversity of forms.’”

The hundred-year war in anthropology is far from over.

If anything the debate is sharpened today by the obfuscations of “politically correct” ideologues, comfortable in their middle-class academic and professional sanctuaries, who hide from difficult class questions of history and social emancipation behind proclamations that the entire planet has been “colonized” by white Europeans.

Contrary to this privileged middle-class world view, the historic tasks confronting humanity remain struggles against the subjugation of women, unresolved national questions the world over, and class solidarity and battles against every form of capitalist oppression and exploitation — the worldwide fight for workers power and socialism.

* * *

“The class struggle is a movement of opposition, not adaptation,” Reed underscores. And that “holds true not only for workers in the plants, but for women as well, both working women and housewives.” This new edition of Cosmetics, Fashion, and the Exploitation of Women is offered as a contribution to that movement and that struggle.

As Reed expressed it in her dedication of Woman’s Evolution, “To women, on the way to liberation.”