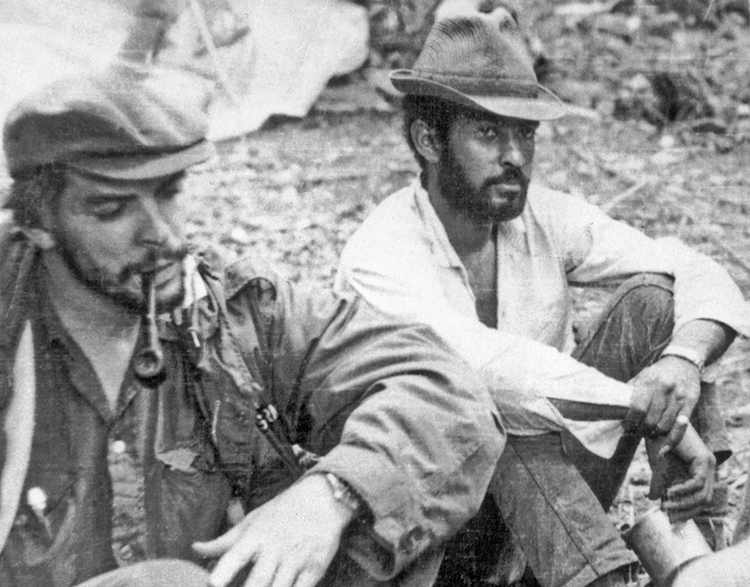

Pombo: A Man of Che’s Guerrilla: With Che Guevara in Bolivia, 1966-68 by Harry Villegas is one of Pathfinder’s Books of the Month for February. Villegas, known the world over as “Pombo,” the nom de guerre given him by revolutionary leader Ernesto Che Guevara, at whose side he fought in the Cuban Revolution, the Congo and Bolivia. The excerpt is from “The Yuro ravine.” In 1966 Guevara went to Bolivia to command revolutionary forces from there and Cuba that were fighting the U.S.-backed dictatorship of René Barrientos. Villegas describes the fighting in which Che was captured and murdered Oct. 9, 1967. Copyright © 1997 by Pathfinder Press. Reprinted by permission.

Everything indicated that Che had retreated down into the ravine, because we heard a series of shots coming from that direction, and later, sporadic firing. That was the moment we lost contact with Che for good.

Urbano, Ñato, and I were trying to climb up to the left ridge when Benigno saw us, made signals, and shouted to us at the top of his lungs not to advance or the army would kill us, because it overlooked our position from the front slope. We climbed down and took positions.

From there, we listened to the voices of the soldiers. One of them shouted: “There are three of them in the ravine.” “Let’s get them out with bazookas and flame throwers.”…

We asked each other about Che. No one had seen him leave. Faced with this dilemma, we lightened up our knapsacks and started to climb up the hill to reach the regroupment point Che had designated. At 9:00 p.m. we arrived and confirmed that a group of our comrades had been there, because we found traces of food (apparently to lighten their knapsacks). Then we remembered that Che had told us of his intention of breaking the encirclement during the night and heading to the Piraypani river in order to reach Valle Grande, looking for the road to Puerto Breto.

We advanced upward, trying to reach the junction with the road going from Pucará to La Higuera. We wound up in a ravine filled with thick vegetation and water, and climbed up to a completely open ridge. Crossing over a hedge atop the summit, we were able to confirm that we were on the road to Pucará. We crossed it with great caution, without leaving footprints, and stopped to rest. Here, I asked a question that was on everyone’s mind: Which would be the best road to take? I asked each comrade to give his opinion. Even though the group was very small and I had been elected leader, decisions needed to be made collectively as much as possible.

Following Benigno’s proposal, we marched to the right to make the crossing as far from the army as possible. The path was hellish, completely open. There were only small, thorny bushes. The earth was sandy. We were advancing three steps only to take ten steps back.

When day came, we hid ourselves better and stationed lookouts. We were in front of the little schoolhouse in La Higuera. At 7:00 a.m. on October 9, a helicopter began to hover above, protected by an airplane. At that time, we thought it might be due to the visit of some high military leaders, including Ovando and Barrientos.

We listened to news on the radio about the army’s capture of a guerrilla fighter who might be Che. We thought it was not possible. At noon, they denied the story and said it was his lieutenant. The description they gave made us think it could be Pacho, because of his physical resemblance to Che. …

During the night, using great caution, we climbed down and saw how the soldiers were singing and dancing and holding a happy celebration. At 9:00 p.m., they were called to formation, which surprised us somewhat. The dogs began to bark. We descended until we reached a creek that had some vegetation and drank a little water with sugar (we had not eaten anything since October 6, when we ate the fritters). We rested and resumed the march at midnight, eventually stumbling into an impassable ravine. We tried to cross it in various places, and in all of them it turned out to be impossible. Then we understood why the army was so confident, because they had made a cordon along the head of the ravine, which was the only place one could get through.

Tying the ropes of the hammocks to the exposed portion of a root, Urbano lowered himself down a cliff. We were able to get down into the ravine, even though the descent was not easy. …

To the right, some two hundred meters away, was a road on which some peasants were descending, accompanied by soldiers.

In the afternoon of October 10, we heard the news of Che’s death. There was no room for doubt; they gave his physical description and the way he was dressed. They mentioned the sweater that belonged to Tuma, which he carried as a keepsake; the two watches: his own and Tuma’s (he was keeping this to give to the son Tuma had never seen); the sandals Ñato had made for him; two pairs of socks (Che always wore two pairs because he had very fine skin and these protected him).

There was a deep silence, we felt indescribable and profound pain. For the first time in my life, tears flowed without needing to have another person cry beside me. I understood more than ever that Che had been a father for me.

We held a meeting in which I communicated the news to the rest of the comrades. I asked Darío and Ñato to decide what course of action they intended to follow, and I asked Inti, as political leader, to give a presentation. I proposed to carry forward the struggle until death and to continue on under the slogan put forward by Che of “Victory or death.”

The following oath was taken: “Che, your ideas have not died. We who fought at your side pledge to continue the struggle until death or the final victory. Your banners, which are ours, will never be lowered. Victory or death.”

A second oath was taken, according to which none of us would abandon the group, much less the struggle. We would continue on together and no one would be taken prisoner.