“We are all in this together” is the daily chorus pushed by the capitalist rulers in the U.S. and around the world today, attempting to cover over the reality that society is sharply class-divided and they aim to survive on our backs. Their goal is to make working people forego the class struggle and hunker down, atomized under imposed isolation. They claim we all face a virus crisis, not a social crisis whose origins are in the downward arc of the capitalist system.

As part of this campaign, an April 3 article in the New York Times argues that the lessons of the 1918-19 “Spanish flu” pandemic — an outbreak far larger and deadly that the one today — proves that social isolation and shutting down the economy is essential.

The fact is that during this time workers worldwide joined in massive class battles amid imperialist war and proletarian revolutions.

When the flu began spreading in the spring of 1918, the first imperialist world war was still raging. Workers refused to turn off the class struggle. The Bolsheviks had just led workers and farmers to power in Russia and were beating back a multisided assault from counterrevolutionary forces backed by eight invading imperialist armies.

Workers and farmers in Germany rose up in the millions in 1919 seeking to emulate the revolution in Russia. A strike wave spread across the U.S., with hundreds of thousands of workers fighting in the streets, including a general strike in Seattle.

That pandemic started in the U.S., Europe and parts of Asia and swiftly spread around the world. A highly contagious wave appeared in the fall of 1918 and successive waves continued in early 1920. Estimates of deaths vary between 20 million and 50 million, and the number of infected up to 500 million.

It first hit the U.S. in August at military bases. To fight their imperialist war, the rulers turned workers in uniform not just into cannon fodder but also incubators of the virus. Forty percent of the Navy and 36% of the Army caught it, and spread it as they trained and were transported to fight abroad.

A shortage of workers during the war had forced concessions from the bosses, improving wages and working conditions. When millions of soldiers came back to join the workforce, the capitalists tried to take all this back.

In 1919, workers responded with a strike wave involving 4 million people, one-fifth of the workforce. Hundreds of thousands of steelworkers and coal miners struck. Tens of thousands of garment workers were out for 13 weeks.

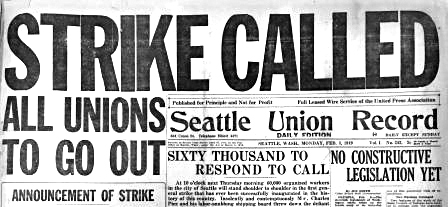

Seattle was hard hit by the flu with some 1,400 deaths. The local government closed schools, theaters, dance halls, restaurants, most public spaces and put all military bases in quarantine. This didn’t stop 60,000 union members from shutting down the city for a week. It was the country’s first general strike.

Eugene V. Debs, a leader of the Socialist Party in the U.S. and supporter of the Bolshevik Revolution, delivered a scathing indictment of the U.S. rulers’ imperialist war policy at a public rally of 1,000 people in Canton, Ohio, in June 1918. He was indicted and sentenced to 10 years imprisonment. Debs ran as the SP candidate for president in 1920 from his prison cell.

Sizable public mobilizations by women took place throughout this period demanding the right to vote. Victory was won with passage of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1920.

Bolshevik Revolution

Led by the Bolsheviks, workers, farmers and soldiers formed soviets — workers councils — and seized power in the October 1917 Russian Revolution.

The flu pandemic didn’t lead Russian workers to turn their back on the class struggle and turn to social isolation. Led by their new government, they began to reorganize society in the interests of the vast majority. At the same time, they built the Red Army led by Leon Trotsky to fight the counterrevolutionary assaults organized by the White Army, backed by eight imperialist powers, including Washington, which landed troops in Vladivostok. Some 2.7 million people in Russia fell to the Spanish flu, including Yakov Sverdlov, one of the central leaders of the Bolsheviks.

Throughout 1919 the Red Army battled Washington’s forces in Siberia, which were backing the counterrevolutionary troops of Russian Adm. Alexander Kolchak. Kolchak and the U.S. forces were defeated by the revolution and Washington withdrew its troops in January 1920.

One of the factors that led to their defeat was a longshoremen’s strike in Seattle in the fall of 1919 that prevented the government from loading arms and munitions for Kolchak.

The lesson is — we aren’t “all in this together.” The working class needs to prepare to defend itself.