The following article was originally published in three parts in the Militant in 2013 on September 23, September 30, and October 7.

Part 1: How Korean workers and farmers began resistance to U.S. domination, forced partition of nation

This year marks the 60th anniversary of the Korean people’s triumph over Washington’s murderous 1950-53 war to conquer that country. The consequences of that war — and the unresolved national division of Korea — continue to reverberate across the Pacific and the world class struggle today.

This summer a Socialist Workers Party leadership delegation of Tom Baumann, James Harris, and me visited Pyongyang, the capital of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, to join celebrations there of the July 27, 1953, cease-fire that registered that historic victory.

Among the anniversary events was the inauguration of a new building and park that substantially expand the Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum, first built in 1953. Although most of the new exhibits were not yet open to the public, we visited the outdoor pavilions displaying captured U.S. and South Korean planes, helicopters, tanks, armored vehicles and ordnance from the Korean War, as well as from military actions by Washington and Seoul right up to recent years.

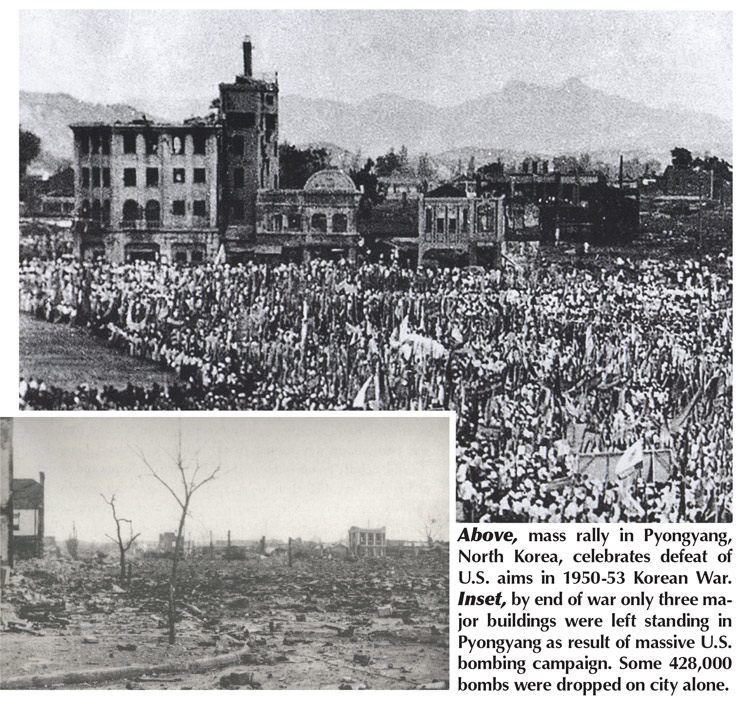

The exhibits included several bombs dropped by U.S. planes during the war. More than 635,000 tons of bombs, as well as 32,557 tons of napalm, were unleashed against Koreans over those three years — 25 percent more than dropped by Washington in the entire Pacific theater during World War II. Some 428,000 bombs were hurled on Pyongyang alone, roughly one per person, according to museum figures.

In towns and cities across northern Korea, and in parts of the South as well, the vast majority of homes, hospitals, schools, factories and other structures were leveled. Only three major buildings were left standing in Pyongyang, and 18 of the 22 largest cities in the North were 50 to 100 percent destroyed.

After Chinese troops joined the DPRK’s fight against Washington’s war of conquest on the peninsula in October 1950, Gen. Douglas MacArthur ordered destruction of every “installation, factory, city and village” in the North up to the Yalu River. Gen. Curtis LeMay, head of the U.S. Strategic Air Command at the time, later wrote, “We eventually burned down every town in North Korea … and some in South Korea too. We even burned down [the South Korean city] Pusan — an accident, but we burned it down anyway.”

And we’re not condemned to rely for facts on beribboned butchers like LeMay. A Pentagon-commissioned study while the war was still on documented U.S. firebombing in the South in summer 1950, as the DPRK’s troops rapidly advanced down the peninsula. “So we killed civilians, friendly civilians, and bombed their homes; fired whole villages with their occupants — women and children and 10 times as many hidden Communist soldiers — under showers of napalm,” the study reported, “and the pilots came back to their [aircraft carriers] stinking of vomit twisted from their vitals by the shock of what they had to do.”

The bombardment continued right up to the July 1953 cease-fire. In the final months, U.S. planes bombed five major dams in the North, causing massive flooding, drowning civilians, destroying the rice crop and livestock for millions and knocking out bridges, railroads and electrical power.

Korea divided in 1945

In September 1945, after a four-decade-long struggle against Japanese colonial brutality and plunder, Korea was ripped in half by Washington and Moscow at roughly the 38th parallel. This trampling on the Korean people’s national sovereignty was the implementation of a joint “trusteeship” cooked up between President Franklin Roosevelt and Premier Josef Stalin as early as February 1945 at the Yalta conference of Allied Powers in World War II. Registering the military situation on the ground in September 1945, southern and northern Korea were occupied respectively by U.S. and Soviet troops. Since 1905 Korea had been under de facto and then direct colonial rule by Japanese imperialism, with Washington’s connivance. The quid pro quo was that Tokyo acquiesced in U.S. imperialism’s colonial rule over the Philippines.

For decades Koreans had been required by Tokyo to speak Japanese rather than their own language, and in 1939 they were ordered to take Japanese names.

Hundreds of thousands of Koreans were enlisted as police or soldiers to enforce their people’s national oppression and, in the 1930s and ’40s, Japan’s occupation of Manchuria in northern China. Millions were transported against their will to Japan to serve as forced labor in mines and factories, or as “comfort women” sex slaves for Japanese soldiers. At the end of World War II, 10 percent of the Korean population was living in Japan.

Korean working people took advantage of Tokyo’s defeat in World War II in August 1945 to advance their fight for national independence and dignity, as well as for land reform, for trade unions and labor rights, women’s suffrage and the expropriation of factories and other workplaces. A revolutionary class struggle spread from one end of the peninsula to the other, pitting the vast working majority against Korean landlords and capitalists who had entrenched their own privileges and profits in collusion with the Japanese occupiers.

People’s Committees were organized across Korea by individuals and organizations long active in the fight against Japanese colonialism. The committees varied in their class composition. Many were dominated by workers and poor farmers, while others were led by businessmen and landlords who opposed Japanese rule.

Korean People’s Republic

On Sept. 6, 1945, two days prior to the scheduled arrival of U.S. troops in Korea, delegates from these committees met and formed the Korean People’s Republic, with Seoul as its capital. Some three-quarters of those proposed for positions in the new government were from groups linked to Moscow and the Communist Party of China and radical petty bourgeois and bourgeois currents of the nationalist movement in Korea. The assembly of the People’s Committees, however, also offered positions to a number of figures such as Syngman Rhee, who had spent all but a few years between 1905 and 1945 living in exile in the U.S. There, for close to four decades, Rhee’s increasingly reactionary political course had been distinguished by pleading on bended knee for Washington to press Tokyo to grant Korean independence — to absolutely no avail — and to forging ties with missionary and various other Protestant Christian institutions. (Aside from the Philippines, where more than 80 percent of the population is Catholic, South Korea has among the highest percentage of Christians, mainly Protestant, anywhere in East Asia: some 10 percent in 1945 and nearing a third today.)

The Korean People’s Republic released political prisoners, organized the distribution of food, and called for national elections as early as March 1946. It announced the confiscation of lands held by the Japanese occupiers and Korean collaborators; an agrarian reform on these and other lands; nationalization of mining, major industries, banking, and transportation; universal suffrage; and a minimum wage and eight-hour day.

But the U.S. ruling families weren’t about to allow the Korean people to establish a government that, as revolutionary struggles deepened, could develop into a workers and peasants power that would replace capitalist rule, and social relations based on class exploitation in countryside and city. They saw Korea as a prize for U.S. capitalism, as well as a stepping stone toward increased domination of China, with its vast lands, more than a half billion exploitable peasants and workers, and lucrative markets for the export of American capital.

U.S. military government

So on Sept. 7, the day before U.S. occupation forces landed on Korean soil, their commander, General MacArthur, decreed that the entire administrative power in Korea south of parallel 38 was under his jurisdiction. The U.S. general warned that, “All persons will obey promptly all my orders and orders issued under my authority. Acts of resistance to the occupying forces or any acts which may disturb public peace and safety will be punished severely.” During the period of military occupation, he said, Korea’s official language would be English. The U.S. military government refused to acknowledge the Korean People’s Republic and continued enforcing the laws of the hated Japanese colonial administration. The U.S. occupiers even kept in place Tokyo’s officials, including Gov. Gen. Abe Nobuyuki.

The Jan. 5, 1946, issue of the Militant ran an account by a U.S. soldier stationed in Korea. The U.S. military government, the GI wrote, “decided that the best thing to do was to freeze the status quo … but the Koreans didn’t see it that way. They just could not understand why the American army employed their hated enemies to continue the oppression of a ‘liberated’ people.”

The establishment of the Korean People’s Republic, the soldier wrote, was seen by the U.S. occupiers as “nothing short of a revolution, and as these people were definitely socialist, it was a ‘communist’ revolution. So we sent in our troops and threw these over-patriotic Koreans out and put back the Japanese and the Japanese collaborators.”

Part 2: U.S. imposed capitalist-landlord gov’t on SKorea

The last issue of the Militant opened this series marking the 60th anniversary of the Korean people’s triumph over Washington’s murderous 1950-53 war to conquer that country. On July 27, 1953, the U.S. government and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea signed a cease-fire agreement in the village of Panmunjom, which straddles the border dividing the northern and southern halves of Korea.

In September 1945, at the end of World War II, the Korean people — after 40 years of fighting Japanese colonial rule — saw their country torn in two at roughly the 38th parallel by the governments of the United States and the Soviet Union.

What’s more, when U.S. occupation forces landed in Korea that month, they refused to recognize the Korean People’s Republic, which had been established in the South by representatives of People’s Committees that had been formed across the country. Instead, Washington not only imposed a U.S. military government but initially kept in place officials of the hated Japanese colonial administration.

U.S. military government

It didn’t take long, as a State Department adviser to the U.S. Army brass in Korea put it, for WashingtonP’s occupation regime to conclude that “removal of Japanese officials is desirable from the public opinion standpoint.” But the State Department official cautioned that Tokyo’s appointees should be removed “only in name,” since “there are no qualified Koreans for other than the low-ranking positions.” He did, however, call attention to a layer of Korean bourgeois figures who could be drawn into governing the country.

“Although many of them have served with the Japanese,” he said, “that stigma ought eventually to disappear.” It didn’t.

A 1947 assessment from the newly established Central Intelligence Agency reported that politics in South Korea was “dominated by a rivalry between Rightists” (whom the U.S. military government had ensconced in power) and a “grass-roots independence movement which found expression in the establishment of the People’s Committees throughout Korea in August 1945.”

Referring to the “numerically small class which virtually monopolizes the native wealth and education,” the CIA noted that “this class could not have acquired and maintained its favored position under Japanese rule without a certain minimum of ‘collaboration.’”

In short, the U.S. spy agency concluded, the newly established government in the South was “substantially the old Japanese machinery,” enforcing its authority through the Tokyo-established National Police, which had been “ruthlessly brutal in suppressing disorder.”

Hoping to pretty up the collaborationist character of the government it was imposing, Washington organized in October 1945 to fly Syngman Rhee from the United States to Tokyo, where he met with U.S. Gen. Douglas MacArthur, and then flew on to Seoul on Mac-Arthur’s personal plane — the Bataan.

“Through its puppet, Dr. Rhee, the [U.S. military government] attempted to engineer a working coalition of the reactionary political parties which would ‘govern’ the country” under U.S. control, the Militant reported in its Jan. 12, 1946, issue.

As U.S. occupation authorities stepped up their attacks on the Korean People’s Republic, they implemented measures that struck directly at the economic and social needs of workers and farmers. First, the military government halted distribution to working farmers of lands confiscated from Japanese landlords. Second, the regime lifted price controls on rice and “reformed” the rationing system, cutting in half by mid-1946 the amount of rice Koreans had been getting under Japanese rule.

Over several days at the end of December 1945 and early 1946, thousands of working people in Seoul poured into the streets and organized strikes calling for an end to the U.S. military government and protesting Washington’s and Moscow’s planned “joint trusteeship” over Korea.

The actions had initially been called by a coalition of the South Korean Workers’ Party and bourgeois currents that opposed the partition. But shortly thereafter — on orders not to embarrass Moscow for its complicity in the division — the South Korean Workers’ Party turned on a dime and condemned the mobilizations.

The Daily Worker, newspaper of the Communist Party in the U.S., denounced the “violent outbursts,” which it said “appeared to have been provoked by extreme right-wingers.” The Militant, to the contrary, said that “fighters for freedom throughout the world hailed the anti-imperialist demonstrations in Korea.”

Beginning in late September and October 1946, strikes protesting the American occupation and demanding food were organized by rail workers, postal workers, electrical workers, printers and others. What began as the Taegu uprising in southeastern Korea spread by November to some 160 villages, towns, and cities across North and South Kyongsang and South Cholla provinces, with peasant rebellions and attacks on the despised National Police.

The police, overwhelmed by the size and scope of the rebellion, relied on U.S. armed forces to crush it. The military government declared martial law. Hundreds of Koreans were killed or injured; thousands were beaten, tortured and imprisoned.

A U.S. soldier who witnessed this bloody repression, Sgt. Harry Savage of Yankton, S.D., described the horrors he had seen in a letter to President Harry Truman. “My name is Sergeant Savage,” he wrote. “I have just been discharged from the army after spending some ten months in the Occupation Forces in Korea. I am writing this now while I have it fresh in mind and while I am eager to do something about it. …

“Why were the American people not told of riots that took place in that country and of the hundreds of people who were killed in those riots?” Sergeant Savage asked. He recounted being deployed to put down an uprising in the coastal city of Tongyong, during which “scores of people were killed.”

Then, a few days later in nearby Masan, “our entire Battalion patrolled that town all day with dead bodies lying all over the streets, and we kept our machine guns blazing.” Many Koreans were beaten and subjected to torture by members of the National Police, he said.

“Many of the GI’s got very angry at this,” Sergeant Savage reported. “Most of the [U.S.] officers however stood calmly by and let these beatings go on without letup. In fact our Division Artillery sent a letter to our Battalion to the effect not to criticize what the police were doing. …

“Most of us thought surely these things would reach American newspapers. About two weeks later the ‘Stars and Stripes’ had an article about it. They said that there had been a riot in Masan, ‘but American troops restored law and order without firing a shot.’”

Syngman Rhee regime

In May 1948 Washington rigged elections for a National Assembly in South Korea. The vote, given the blessing by United Nations inspectors, was restricted to landowners, to taxpayers in towns and cities, and, at the village level, to elders. The new assembly established the Republic of Korea, with Syngman Rhee as president. Inaugural ceremonies were held in August. Rhee maintained his corrupt and brutal regime until 1960, when a mass uprising by workers and youth overturned it.

As Rhee was being anointed in Seoul, South Korean troops and police, backed by Washington’s occupation forces, were brutally suppressing a rebellion on Cheju Island, 60 miles below the peninsula’s southernmost tip.

Actions denouncing the U.S.-engineered elections and demanding food and jobs had begun there in March 1948. In face of government arrests and killings, there was an armed uprising on April 3, led by the South Korean Workers’ Party and other forces.

Expressing the imperial arrogance and contempt for working people that distinguished the U.S. occupiers, Col. Rothwell Brown wrote at the time that the ranks of the fighters were “ignorant, uneducated farmers and fishermen.”

The uprising had largely been crushed by the summer of 1949. “The job is about done,” U.S. Ambassador John Muccio wired the State Department in May.

According to the government’s own figures, at least 30,000 people on Cheju Island had been killed out of a population of no more than 300,000. More recent estimates place the figure as high as 80,000 dead.

In a brutal campaign later used by Washington during the Vietnam War as a model for its “strategic hamlets” program, South Korean troops and police drove peasants from their homes into heavily fortified villages. By the end of the bloodletting, only 170 of 400 villages remained on Cheju; nearly 40,000 homes had been destroyed; and tens of thousands had taken refuge in Japan.

Another uprising began in October 1948, in the southeastern city of Yosu. There many soldiers in the Korean army’s 14th and 6th regiments rebelled in face of orders to go to Cheju and take part in a bloody crackdown on fellow Koreans.

According to an article by Joseph Hansen in the Nov. 8, 1948, issue of the Militant, a dispatch in the New York Herald Tribune reported that when orders came for deployment to Cheju, rebel troops instead killed “all the loyal officers at Yosu and seized an arsenal of American and Japanese weapons.” Hansen wrote that soldiers seized a train and went to nearby Sunchon, where they “ran up the flags of the North Korean People’s Republic” — established just weeks earlier on Sept. 9 — and were joined by hundreds of local residents.

The rebellion was quelled by Korean troops under the command of U.S. officers.

The Militant’s account of the Herald Tribune dispatch continued:

More than 5,000 men were rounded up on the playing field of a school [in Sunchon] for questioning “to find out where they were during the rebellion and how they acted.” Batches were then executed on the spot. “One of the first sights to meet the eyes of American correspondents reaching here today was a rifle squad of executioners standing over fallen enemies.” …

The report concludes: “The four American correspondents at the scene of the fighting here have been urged strongly to point out that if the American troops are taken from the area in the discernible future, the whole country is sure to be conquered by organized Communists.”

By July 1950, even before Washington launched its murderous war in Korea, more than 100,000 workers, peasants, and youth had already been killed by the landlord-capitalist regime and the U.S. occupation army that imposed it on the southern half of the divided country.

Part 3: Korean War: U.S. rulers aimed to crush fight for sovereignty, against capitalist rule

This series marks the 60th anniversary of the Korean people’s victory over Washington’s 1950-53 war to conquer that country. The first two parts have told the story of Korea’s partition in 1945 at the hands of Washington and Moscow and of the brutal landlord-capitalist regime imposed by the U.S. armed forces on the southern half.

“Acts of resistance to the occupying forces or any acts which may disturb public peace and safety will be severely punished,” warned Gen. Douglas MacArthur in his Sept. 7, 1945, proclamation establishing the interim U.S. military government in South Korea. And that’s what workers and peasants faced, as more than 100,000 Koreans were killed over the next half decade (and many more beaten, tortured, or jailed), as the U.S. occupiers and their local collaborators suppressed strikes, land seizures and uprisings.

Meanwhile, north of Korea’s 38th parallel, a Central People’s Committee was established in February 1946, with Kim Il Sung, a leader of the liberation movement against Tokyo’s colonial boot since the 1930s, as chairman. The new workers and peasants government recognized peasant land seizures and organized a sweeping agrarian reform; expropriated the landlords and capitalists, both Japanese and Korean; and carried out other social measures in the interests of working people.

On Sept. 9, 1948, in response to the imposition of the Syngman Rhee regime in Seoul through U.S.-rigged elections, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea was established in Pyongyang.

Korean War

When war erupted between the two governments on June 25, 1950, the U.S. rulers backed to the hilt the Rhee regime’s efforts to reimpose the dictatorship of capital in the north. At the time, many in the U.S. ruling class also hoped their troops could march beyond the Yalu River and strike a fatal blow to the Chinese Revolution, which had triumphed in 1949. Within two days, Washington arranged United Nations Security Council cover to deploy armed forces from the United States and U.S. allies in what President Harry Truman labeled a U.N. “police action” to “suppress a bandit raid on the Republic of Korea.”

On direct orders from Premier Joseph Stalin, Soviet Ambassador Jacob Malik didn’t show up for the Security Council vote, where he would have been able to veto the U.S. resolution. Moscow’s pretext was that it was boycotting the Security Council to protest Washington’s decision to block the People’s Republic of China from U.N. membership. But the real reason — to avert a showdown with Washington — was laid bare less than a week later when the Soviet Union’s turn as Security Council chair came around and Malik’s “principled boycott” abruptly ended.

Over the next three years, some 2 million U.S. soldiers were sent as cannon fodder to Korea, along with more than 160,000 troops from 15 other countries, with the largest numbers from the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and Turkey.

The DPRK’s Korean People’s Army rapidly liberated 90 percent of the peninsula, down to a small southeastern corner of the country that became know as the “Pusan perimeter,” from the name of the coastal city it encircled. When a U.S. regiment arrived by ship in Pusan in mid-July, Korean dockworkers were on strike and refused to offload their weapons. The U.S. troops either unloaded the equipment themselves or forced Korean longshoremen to do so at gunpoint.

Rhee and his chief cronies fled Seoul as soon as the fighting began, with the top officer corps trailing behind two days later. By the day after that, June 28, less than a quarter of South Korean troops could be accounted for, and most of their heavy weapons and equipment had been abandoned, destroyed, or captured.

Unburying the truth

The tenor of much of the war coverage in the U.S. capitalist press is illustrated by a couple of July 1950 dispatches by Hanson Baldwin, the Pulitzer Prize-winning military editor for the New York Times. Calling the DPRK troops “invading locusts,” Baldwin wrote, “We are facing an army of barbarians in Korea, but they are barbarians as trained, as relentless, as reckless of life, and as skilled in the tactics of the kind of war they fight as the hordes of Genghis Khan.” Acknowledging outrage among Koreans at the “women and children slain by American bombs” in the war’s first weeks, Baldwin added that the U.S. armed forces must show that “we do not come merely to bring devastation” but instead convince “these simple, primitive, and barbaric people … that we — not the Communists — are their friends.”

When CBS radio correspondent Edward R. Murrow posed the question in a taped broadcast how Koreans in “villages to which we have put the torch” during the flight to Pusan might view “the attraction of Communism,” top network executives refused to air it.

Aside from the pages of the Militant, one of the few places factual information could be found in those years, much of the truth about what had happened in Korea only began to come out under the impact of the fight for national reunification by the Vietnamese people in the 1960s and 1970s, and the worldwide movement against the U.S. war there.

These revelations were also spurred by a new rise of struggles in South Korea against the U.S.-backed tyranny, above all the 1980 Kwangju rebellion in which thousands of armed workers took over the city. Hundreds were killed in Kwangju by Seoul’s police and troops, aided by U.S. forces there, but a few years later the reverberations of that battle and others across South Korea brought down the dictatorship of Chun Doo-hwan.

The 60th anniversary of the Korean War has spurred the publication of several new books telling more of the truth about its roots and consequences. One is The Korean War: A History (Modern Library, 2010) by Bruce Cumings, who has written other valuable accounts over the past 30 years. This summer has seen the release of Brothers at War: The Unending Conflict in Korea (Norton, 2013) by Sheila Miyoshi Jager. Another useful book (especially regarding conditions facing U.S. and other “U.N.” troops), published on the 50th anniversary, is: MacArthur’s War: Korea and the Undoing of an American Hero (Simon & Schuster, 2000) by Stanley Weintraub, who was a GI in Korea during those years. Much of the information in these articles comes from these books, as well as from the pages of the Militant since 1945.

In addition, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Korea — established in 2005 by the South Korean government to investigate atrocities before, during, and after the war, and dissolved five years later for doing its job too well — uncovered evidence of the murder of between 100,000 and 200,000 people by South Korean authorities between 1945 and 1953, as well as 138 massacres by U.S. forces during the war.

The commission was spurred in large part by the widely reported exposure in 1999 of a July 1950 massacre by U.S. troops of some 400 civilians in the village of No Gun Ri, one of many such atrocities by South Korean and U.S. forces covered up for half a century by the bourgeois press in the United States and elsewhere. Among the documented cases committed by South Korean forces during their flight from Seoul in July 1950 was the slaughter and mass burial of some 4,000 people in the city of Taejon, site of one of the most hard-fought battles during the opening weeks of the war.

Invasion at Inchon

In September 1950, as South Korean and U.S. forces were facing defeat, some 80,000 U.S. Marines invaded at Inchon Harbor near Seoul. Over the next several weeks, the armed forces of the DPRK organized a retreat north from the Pusan perimeter. But General MacArthur’s bombastic promise to U.S. troops that they would be “home by Thanksgiving,” and then “home by Christmas,” was a sham. As U.S. soldiers approached the Yalu River, separating Korea from China, some 260,000 Chinese troops crossed the border to aid the DPRK’s forces in pushing back the invasion. What’s more, MacArthur — who himself never spent a single night in Korea during the war, flying back to the comforts of Tokyo after each visit — hadn’t equipped U.S. soldiers for the bitter-cold Korean winter. Many suffered from frostbite, and their weapons and other equipment wouldn’t function.

In early 1951, at a low point in the morale of U.S. forces, Gen. Matthew Ridgway took over operational command and managed to hold on to a line at roughly the 38th parallel. The murderous U.S. bombardment of North Korea described in the first article in this series — leveling Pyongyang and scores of other cities, towns, and villages — had not broken the will of the Korean people.

Nor had the Truman administration’s threats, in face of the aid being given to Korean liberation forces by Chinese troops, to unleash nuclear weapons. “We will take whatever steps are necessary to meet the military situation,” Truman said at a Nov. 30, 1950, press conference — including attacks on China itself and “active consideration” of using the atomic bomb.

So in July 1951 the U.S. government agreed to begin cease-fire talks with the DPRK. As the war became increasingly unpopular among working people in the U.S. over the next two years, the new Republican administration of Dwight Eisenhower finally signed an armistice at the Korean village of Panmunjom near the 38th parallel on July 27, 1953.

By most estimates, more than 4 million people were killed in the U.S.-organized war, including at least 2 million civilians. The big majority of deaths were of Koreans — some 10 percent of the peninsula’s prewar population — with hundreds of thousands of Chinese killed or wounded as well.

More than 40,000 soldiers from the U.S. and other allied countries were killed; some 115,000 wounded; and more than 7,500 U.S. troops still listed as missing in action. Proportionally, the highest rates of deaths and wounded were among troops of the so-called U.N. forces sent as cannon fodder by allied governments to help give cover to Washington’s war. Of the first 300-man unit of troops from Turkey to see combat, only 45 survived; altogether the casualty rate for Turkish troops (deaths and injuries) was 20 percent. Rates between 13 and 32 percent were also suffered by troops from Belgium, Ethiopia, France, Colombia, Greece, Luxembourg and the Netherlands.

How the ‘Militant’ campaigned

The Militant campaigned to halt the imperialist war in Korea. As the socialist weekly had done in covering struggles by Korean working people over the half decade prior to the war, it scoured the bourgeois press for whatever facts slipped through and ran accounts by GIs or merchant seamen who had ended up in Korea. Among the well over 200 articles, editorials, and statements by Socialist Workers Party candidates during the first year and a half of the conflict alone, some of the headlines read: “SWP Candidate Hits Intervention in Korea,” “Jim Crow in Korea,” “The Real Role of the UN,” “War Reporters Describe U.S. Atrocities in Korea,” “Labor Should Demand: ‘No War with China!’,” “U.S. Army Censor Holds Reporter ‘Incommunicado’,” “Millions in Korea Flee U.S. Bombs,” “Rhee’s Soldiers Massacre Entire So. Korea Village,” and “Korea War a Year Old — Stop the Slaughter Now — Acheson Compelled To Admit ‘Police Action’ Is Real War.”

In 1950 and 1951 the working-class newsweekly featured three letters from Socialist Workers Party National Secretary James P. Cannon to President Harry Truman and members of the U.S. Congress.

“This is more than a fight for unification and national liberation,” Cannon wrote in the first letter, dated July 31, 1950, just a few days after U.S. troops entered the combat. “It is a civil war. On the one side are the Korean workers, peasants and student youth. On the other are the Korean landlords, usurers, capitalists and their police and political agents. The impoverished and exploited working masses have risen up to drive out the native parasites as well as their foreign protectors. …

“Your undeclared war on Korea, Mr. President, is a war of enslavement. That is how the Korean people themselves view it — and no one knows the facts better than they do. They’ve suffered imperialist domination and degradation for half a century,” Cannon wrote, “and they can recognize its face even when masked with a UN flag. …

“I call upon you to halt the unjust war on Korea. Withdraw all American armed forces so that the Korean people can have full freedom to work out their destiny in their own way.”

Cannon’s second letter was written on Dec. 4, 1950, after Chinese troops had come to the aid of Korea and amid Truman’s nuclear saber-rattling. “Your reckless adventure in Korea has brought this country into a clash with the 500 millions of China and threatens an ‘entirely new war,’” Cannon wrote. “Your proposed solution, Mr. President, is a threat to repeat the atrocities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki by using the atom bomb in Korea. … Stop the war NOW!”

Three years later, after the July 1953 cease-fire, the Militant hailed the Korean people’s defeat of Washington’s war aims and drew lessons from imperialism’s bloody assault. “Giant armies have been pitted for three years in ferocious combat against each other; unsurpassed concentrations of firepower have been used; casualties have run into the millions and property destruction has been almost total,” said an article in the Aug. 17 issue.

The cease-fire in Korea, the Militant said, registered “the fact that the United States, the foremost capitalist power and chief military spearhead of world imperialism, for the first time in its history has come out of a war without a victory.”

U.S. refuses to sign peace treaty

Over the six decades since the 1953 armistice in the Korean War, the U.S. government has nonetheless maintained an official state of war on the peninsula, refusing to this day to sign a peace treaty with the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. Among other things, Washington maintains 28,500 troops in South Korea and conducts provocative joint military exercises with Seoul every year. As part of Washington’s efforts to isolate and strangle the people of North Korea, this year alone it has taken the initiative to slap the DPRK with two new sets of economic and financial sanctions, adopted Jan. 22 and March 7 by the U.N. Security Council. These sanctions tighten restrictions on the DPRK’s banking transactions and access to trade credits, as well as expanding the list of banned imports. The measures also imposed mandatory interdictions — aka piracy — of North Korean ships and aircraft suspected of transporting such proscribed goods.

Since mid-July Panamanian authorities, at Washington’s bidding, have detained a North Korean cargo ship sailing from Cuba as it prepared to cross the Panama Canal. The government of Panama, saying it acted on a “tip” from U.S. intelligence that the Chong Chon Gang was smuggling drugs, now claims the cargo violates the U.N. arms embargo. The vessel was transporting sugar, as well as Cuban arms for repair in North Korea.

Washington’s pretexts for the two most recent rounds of sanctions were the DPRK’s successful launching of a satellite into orbit last December and a nuclear weapons test in February. The hypocrisy and imperial arrogance of the U.S. rulers are shown by two facts: (1) of the more than 1,000 satellites in orbit as of May 2013, some 43 percent are of U.S. origin — 12 percent openly for military purposes; and (2) of the 2,053 nuclear tests since 1945, 1,032 have been conducted by Washington and three by Pyongyang.

What’s more, Washington openly maintained tactical nuclear weapons on South Korean territory until 1991. And nine U.S. nuclear-armed submarines prowl the Pacific, each one outfitted with missiles (with a range of more than 5,500 miles) and nuclear warheads equal in their heinous payloads to some 6,000 times the imperialist holocaust unleashed against Japanese and Korean residents of Hiroshima in August 1945.

As the Socialist Workers Party National Committee wrote in a recent message to the Central Committee of the Workers’ Party of Korea on the 65th anniversary of the founding of the DPRK, “The people of Korea, Asia, and beyond have no interest in these monstrously destructive weapons and aspire to a world free of them once and for all. …

“US troops and weapons out of Korea and its skies and waters! For a peninsula and a Pacific free of nuclear weapons!

“Korea is one!”

Click here to download PDF