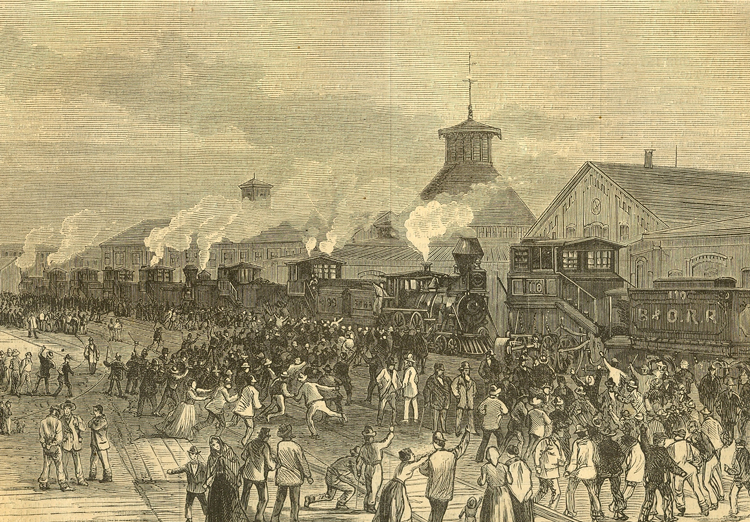

The “Great Strike” of 1877 started among rail workers and then drew in more than half a million overall. Karl Marx wrote that the strike “could very well be the point of origin for the creation of a serious workers’ party.” It was sparked by starvation wages and brutal working conditions. It struck fear in the rulers, who denounced “mob rule” and blamed a communist conspiracy.

Federal, state and city governments unleashed troops, armed cops and gangs of thugs on the strikers, cheered on by the bourgeois press. In the course of this mighty class battle, more than 100 workers were killed.

Below are excerpts from Philip S. Foner’s The Great Labor Uprising of 1877, one of Pathfinder’s Books of the Month for July. Copyright © 1977 by Philip S. Foner, Pathfinder Press. Reprinted by permission.

The Great Strike of 1877 occurred six years after the Paris Commune — the working class-led revolution which took power in that city on March 18, 1871, and, for the seventy-two days of its existence, established a new type of state. The news of the “Revolution of March 18” produced a wave of fear throughout the established circles in both Europe and the United States. It soon became the practice to blame the social tensions in the United States on foreign influence, and this technique was employed with increasing frequency during the economic crisis of the 1870s. During the troubles on the railroads in 1873-74, there were some references to the fact that the strikers were determined to establish a Commune in the United States. But it was in the Great Strike of 1877 that a large portion of the press came to view the outbreaks as the “long-matured concerted assertion of Communism throughout the United States.” …

The speed with which the Great Strike moved across the country was positively breathtaking. On July 18 the strike, which had begun in West Virginia, spread to Ohio; one day later, it reached Pennsylvania, and a day after that, New York. On Sunday and Monday, July 22 and 23, thousands of workers throughout the eastern and midwestern sections of the country went on strike. By noon on Tuesday, July 24, the Great Strike had ripped through West Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, New York, New Jersey, Ohio, Indiana, Kentucky, Missouri, and even Iowa. The New York World estimated that day that it involved more than eighty thousand railroad workers and over five hundred thousand workers in other occupations. Aside from the walkouts of workers in sympathy with the railroad men, thousands of businesses that were dependent upon the railroads for their supplies — factories, mills, coal mines, and oil refineries — were forced to shut down. In Cleveland, for example, the effects of the stoppage on the Pennsylvania Railroad system were felt as early as Monday morning, July 22, and the Cleveland Leader noted that the closing down of the Cleveland & Pittsburgh line (a subsidiary of the Pennsylvania Railroad) by “rioters” had cut off an “important source of supply for fuel”:

As a direct consequence of this, all the mills and furnaces of the Cleveland Rolling Mill Company and the Northern Ohio Iron Company are shut down. The Standard Oil Company, with its legion of employees, will stop work this morning for lack of transportation. No less than six foundries in this city will be forced to suspend operations today.

By Wednesday, July 25, all the main railway lines were affected, and employees of some Canadian roads were also joining the strike. By this time, it was a thoroughly national event. Business in many cities was feeling the effect of the freight blockade; for example, New York’s supply of western grain and cattle had been completely cut off. There were strike reports from such scattered points as Kansas City, Chicago, Indianapolis, Terre Haute, Columbus, Cincinnati, Louisville, Pittsburgh, Baltimore, East St. Louis, and St. Louis. Illinois Central trains were stopped at Effingham, Malltown, Decatur, and Carbondale, Illinois. Governor Cullom of that state declared in his 1879 biennial message that “the railway trains and machine shops and factories in Chicago, Peoria, Galesburg, Decatur, and East St. Louis were in the hands of the mob, as well as the mines at Bradwood, La Salle, and some other places.” …

The Great Strike, which was described in the WPUS [Workingmen’s Party of the United States] journal, Labor Standard, as “The Second American Revolution,” became the springboard for political and trade union action by the American working class. It was able to assume this character because it was more than a strike movement against wage cuts. It was a social rebellion, the first assertion by a national working class of a common anger against a variety of grievances — years of brutal exploitation, and a system of industrialization which viewed the worker as little more than part of the machine, who could be discarded the moment he was no longer needed, and which required him to adjust to a deadening routine of work that made him practically part of the machine. It was the first real evidence of working class collective power capable of imposing its own will upon future social developments. Workers from New York to San Francisco understood, for the first time, their potential power. …

Writing to Friedrich Engels, Karl Marx called the Great Strike “the first uprising against the oligarchy of capital which had developed since the Civil War,” and predicted that while it would be suppressed, it “could very well be the point of origin for the creation of a serious workers’ party in the United States.” Other contemporaries also understood the broader implications of the vast labor upheaval, but the Washington Capital probably put it best just a month after it ended:

Capitalists may stuff cotton in their ears, the subsidized press may write with apparent indifference, as boys whistle when passing a graveyard, but those who understand the forces at work in society know already that America will never be the same again. For decades, yes centuries to come, our nation will feel the effects of the tidal wave that swept over it for two weeks in July.