![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

LOS ANGELES — “Wendy Lyons was a central leader of the Socialist Workers Party for many years. She was a political leader of the working-class movement in this country,” Norton Sandler, speaking on behalf of the SWP National Committee, told a meeting celebrating Lyons’ life and political contributions here July 15. One hundred and six people attended the meeting. Lyons, a member of the party for 55 years, died a month earlier at 73.

The meeting was held at the United Food and Commercial Workers Local 770 Workers’ Center, the union Lyons was a member of when she worked on the production line at Farmer John’s meatpacking plant. Pedro Albarran, a shop steward for the UFCW at Farmer John, welcomed everyone to the meeting. Lyons had been his co-worker.

“Wendy was both a leader of the party’s practical work,” Sandler said, “and took important responsibilities in the theoretical and programmatic debates that steered the course of the party in the world at a decisive time.”

SWP members and supporters, co-workers from factories where she worked, and many who she joined with in working-class struggles over the years came to the meeting. Her companion Al Duncan, her two brothers and sister, and numerous other family members attended. Dennis Richter, organizer of the Los Angeles SWP branch, chaired.

“At a young age Wendy gained a hatred of capitalism — its racism, its wars, its day-to-day indignities, cultural and political, directed at the working class,” Sandler said. “She became convinced that building the Socialist Workers Party was decisive in the working class’s battle to overthrow capitalism.”

Sandler said the SWP is striving to build the working-class vanguard necessary to face and defeat the U.S. ruling class, the most brutal in history. “Leadership is a decisive question,” he said.

Leader of leaders

“Two big events won Wendy to a lifelong course of building the revolutionary party in the U.S.,” Betsey Stone, a member of the SWP in Oakland who had worked with Lyons for decades, told the meeting. “The Cuban Revolution in 1959 and the mass working-class struggle that tore down the system of Jim Crow segregation in the South.”

“I have been part of the fight for justice for working people since I was a teenager,” Lyons told a reporter when she ran for mayor of Los Angeles in 2005. “The civil rights movement taught me a determined fight by working people could change history. The Cuban Revolution showed me that if workers and farmers take political power they can begin to solve things that seem unsolvable under the capitalist system we live under.”

Lyons had a thirst for Marxist education and played a role in organizing and leading party classes. Stone said she and Lyons attended a 1981-82 session of the party’s leadership school, where comrades took a six-month sabbatical from daily leadership assignments to collectively study the revolutionary activities and writings of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, the founders of the communist movement.

Students at the school also studied Spanish. Lyons conquered enough, Stone said, that she could carry on political discussions with co-workers in Spanish for the rest of her life.

“Wendy didn’t have a self-serving bone in her body,” Sandler said. “She was a leader of leaders, one of a dozen or so younger cadres of her generation who shouldered greater and greater responsibilities in the party. By the time she was 28, she served as the party’s representative on national anti-Vietnam War coalitions and had been organizer of the party’s two largest branches, in New York and Los Angeles.

“She was a leader in the party’s participation in the women’s liberation movement and in theoretical battles for clarity in the debates in our party and world movement,” he said.

Lyons was elected to the SWP National Committee in 1973, as part of a key leadership transition in the party. She was one of a number of younger leaders elected, he said, as several veteran leaders with decades of class-struggle experience and shouldering substantial party responsibilities stepped down. Lyons served on the NC for 25 years, and for many years on its Political Committee.

Leader of party trade-union work

As capitalism began its long downward spiral in the 1970s, a spiral still unfolding today, a series of significant labor battles broke out. The SWP responded by organizing its members and leaders to get union jobs in basic industry — rail, coal, auto, steel and others.

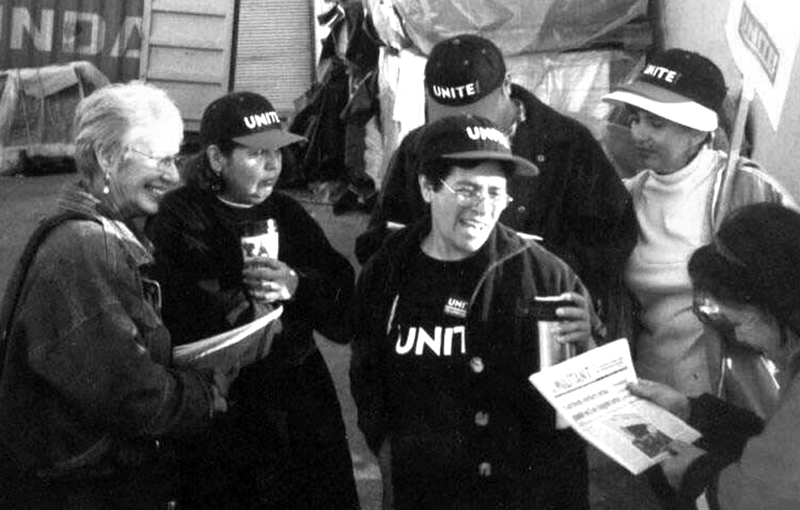

Lyons worked on the production line in meatpacking plants and in garment factories. She was elected the national organizer of party members’ trade-union work in those industries for periods in the 1980s and ’90s.

This was also when women were breaking into industrial production jobs previously off-limits. Many became among the most conscious unionists, knowing that without using their unions and fighting alongside male co-workers, they wouldn’t stand a chance against boss attempts to divide the workforce and turn other workers against them.

“The bosses do not accept the fact that women are here to stay in industrial jobs,” Lyons said in a report she gave to a meeting of women comrades working in industry at the party’s convention in 1979. “They want to maintain our status as second-class citizens, as part of the reserve army of the unemployed that can be shunted in and out of the workforce. This is the root of sexist harassment on the job.”

Women’s oppression is based on the ascendancy of private property — today enforced by the capitalist rulers.

Her remarks remain a model of how to address the challenges facing women from discrimination and prejudices on the job. This working-class approach is the opposite of the individual shaming of men and the score-settling that is the course of today’s #MeToo movement.

Joe Swanson, a party member in Nebraska, was a railroad switchman when he met the party in the late 1970s. In a letter he described meeting Lyons.

“Wendy was especially interested when I shared a recent experience of my rail union local taking a stand in support of women recently hired and being treated as equals on the job,” Swanson said. “I explained that the local voted that if a woman, a union sister, could not throw a switch, then you as a man, a union brother, cannot either, and the switch crew better call out the track workers to fix the switch.”

Lyons won many to back the party

“She deeply cared about the plight of the working people. That was her life,” Mike Isley wrote, saying he met Lyons when she visited him and other copper miners on strike in Arizona in 2005. She stayed in touch with him after he retired to his ranch in Idaho, making sure he kept his Militant subscription up and garnering contributions for the party.

The Communist Leagues in Canada, New Zealand, United Kingdom and Australia, sister organizations of the SWP, also sent messages.

Lyons battled with cancer off and on for nearly two decades. It slowed her down, but never stopped her. Jim Herrera, a leader of the party in Los Angeles, explained how Lyons insisted on continuing to work and do politics on the job, putting in a couple hours a day at Home Depot.

“Many, many times she would find a way to go campaigning door to door for the party in working-class communities,” he said. “She followed politics closely and loved to discuss what was happening with workers. And Wendy was a good listener too.”

Herrera and a number of others recounted working with Lyons to prepare party educational programs. She studied with discipline and a contagious excitement throughout her life.

“Wendy was one of the most cool-headed, solid proletarian fighters I had the pleasure to work with,” Becca Williamson from Seattle wrote. “If the branch was getting twisted up trying to figure out what to do about something, she would join the discussion with a clear political intervention that would cut through to what would help advance the working-class struggle, and make it clear what should be done.”

People stayed for a wonderful selection of food and refreshments, and to study a display capturing events during Lyons’ life. They responded to an appeal for funds to help advance the work of her party, donating $7,100.

“It’s fascinating,” Shanique Irby, one of Lyons’ granddaughters, said while looking at the display panels on her life. “I knew she spent her life doing this but not all these things. It inspires me to do a lot more with my life.”

Rachel Bruhnke remembered meeting the Socialist Workers Party when Lyons came knocking on her door in San Pedro. “She put the Militant in my hand and I said, ‘Are you kidding? This is great,’” Bruhnke said. “I learned today about how much she was involved in the leadership. I wouldn’t have guessed that about this unpretentious woman who sat in my living room and discussed politics with me.”