In the name of defending women, student protesters and administration officials at Harvard University struck a serious blow against political rights by stripping responsibilities from a longstanding faculty dean in the law school who took on the controversial job of joining the legal defense team for movie producer Harvey Weinstein. Weinstein faces multiple accusations of sexual harassment and rape.

At stake are rights vital to the working class — that one is innocent until proven guilty, no matter how heinous the charges may be; the right to speak and associate freely as guaranteed by the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution; and the Sixth Amendment right to a lawyer who can provide vigorous counsel to those facing charges by the state.

On May 11 Harvard University announced that it was ending the appointments of law professor Ronald Sullivan Jr. and his wife, lecturer Stephanie Robinson, as faculty deans of Winthrop House, a residence for some 400 students. They had held these positions for a decade, and were the first Black professors in Harvard’s history to be appointed to these positions. Both still remain professors at the law school.

Sullivan is director of the Criminal Justice Institute at Harvard Law. In addition to teaching law, he is a longtime criminal defense attorney, who has been involved in a variety of high profile cases. He represented the family of Michael Brown, who was fatally shot by police in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014. He took on the case of former New England Patriots star Aaron Hernandez, who won acquittal after being charged with double murder. He organized a legal campaign that helped free thousands of people incarcerated without due process in Louisiana after Hurricane Katrina.

Campaign against Sullivan

But when Sullivan announced in January that he was joining Weinstein’s defense team, a hue and cry went up by some so-called politically correct students demanding that he be ousted. In February two Harvard undergraduates wrote an op-ed piece in the campus newspaper titled, “Harvard, Remove Dean Sullivan,” claiming his presence “could be deeply traumatic” and that he does not value “the safety of students.”

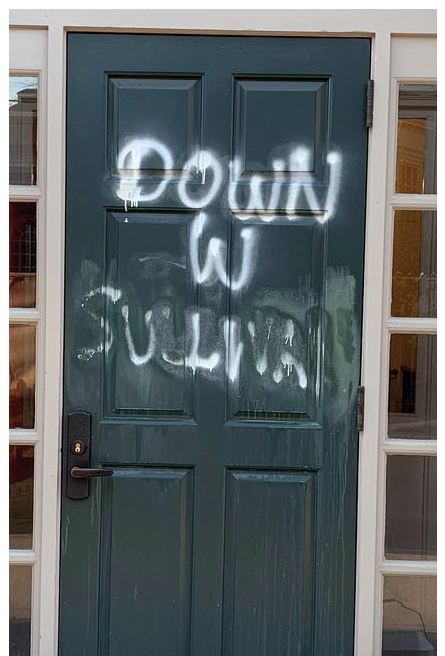

Graffiti was spray painted on Harvard buildings and on Sullivan’s office door that included slogans saying, “Our rage is self-defense” and “Whose side are you on?” Dean of Harvard College Rakesh Khurana then initiated a review of “the climate” at Winthrop House, including questioning students about whether they found the dormitory “sexist” or “non-sexist.”

Sullivan responded to the campaign against him with an email sent to all those involved with Winthrop and offered to meet with anyone who wanted to discuss the questions involved.

“It is particularly important for this category of unpopular defendant to receive the same process as everyone else — perhaps more important,” he wrote. “To the degree we deny unpopular defendants basic due process rights we cease to be the country we imagine ourselves to be.”

Others on the campus came to Sullivan’s defense. There is “such a stigma attached to people accused of sexual misconduct that anyone who defends legal principles on their behalf risks being mistaken, in the public mind, for a defender of sexual violence,” Harvard Law School professor Jeannie Suk Gersen wrote in the New Yorker.

On May 6 some 175 students protested in the Winthrop dining hall holding #MeToo and “Reclaim Winthrop” signs. Five days later Khurana announced that Sullivan and Robinson would no longer be faculty deans when their terms end June 30.

What’s at stake for working class

“I am not personally accused of engaging in any misconduct,” Sullivan said in a March 7 interview with the New Yorker. “Lawyers do not represent the ideology of their clients. Rather, lawyers are engaged in a long-standing tradition of service to people accused by the state.”

“I have gotten scores of notes from students who very quietly give strong support to me, and I appreciate those notes,” he added. “But one constant is that they say that they feel as though they cannot say anything publicly because they will be tarred and feathered as ‘rape sympathizers’ and that they’re disinclined to step out publicly.”

“People have to be able to exchange ideas, even ideas with which they disagree, freely and openly,” he said.

“Regardless of where moves to attack political rights or to victimize people for acting on their beliefs begin,” Seth Galinsky, Socialist Workers Party candidate for New York City public advocate, said May 17, “the capitalist rulers look to turn this against the working class and the communist movement. For years the Socialist Workers Party, Communist Party, groups fighting against Jim Crow segregation in the South and others faced serious challenges finding lawyers to defend them when the government tried to frame them up and shut them down.”

“The right to have legal counsel to vigorously fight charges by the state will become even more important for working-class political organizations as the class struggle heats up,” he said.