A Lorain County jury June 7 ruled in favor of a lawsuit by Gibson’s, a family-owned and operated bakery, and its proprietors David and Allyn Gibson, against Oberlin College and Meredith Raimondo, the vice president and dean of students of the northern Ohio college.

The suit charged the college and Raimondo with libel, saying they had carried out a “malicious campaign to permanently harm and damage [Gibson’s] through publishing false statements.” These include smears that “the bakery is a ‘racist establishment with a long account of racial profiling and discrimination’” and that the Gibsons “commit hate crimes against minorities.”

The case received widespread national press coverage. Articles and opinion pieces have appeared in the New York Times, Washington Post, Wall Street Journal and Forbes magazine, as well as Ohio-area newspapers and TV stations. Much of the reporting in the liberal media echoed allegations by college officials that the verdict poses a danger to the First Amendment — that the college is being held accountable for the speech and actions of its students.

Oberlin is a company town of just over 8,000 people, dominated by the college, whose student body comes from largely upper-middle-class families, more than half from New York, California, Illinois, Ohio, Massachusetts and New Jersey. “In a small city like Oberlin, having the largest business and employer against you is more than enough to seal your fate,” David Gibson wrote in an article in USA Today published after the verdict.

Smear campaign

The Gibson’s complaint described how Raimondo and other Oberlin College authorities orchestrated a demonstration outside the bakery and distributed a libelous flyer saying its “owners racially profiled and discriminated against” three students. The students had been arrested after one of them tried to use a fake ID and shoplift two bottles of wine from the bakery on Nov. 9, 2016, and then pummeled a store employee who pursued them.

The three students, who are Black, pleaded guilty to misdemeanor charges, including theft, in 2017, and acknowledged that the shop owners’ response had not been racially motivated.

Jason Hawk, editor of the Oberlin News Tribune, testified during the trial that Raimondo tried to block him from taking pictures of the protest, telling him he had no right to do so. Hawk also testified he saw Raimondo handing out flyers stating that Gibson’s was “racist.” The flyer urged a boycott of the bakery and informed people where else they could shop.

Emily Crawford, a worker in the college’s communications department, wrote an email to her supervisor warning the administration not to pursue the slanders against the small store and its owners. “I have talked to 15 townie friends who are PoC [persons of color],” she said, “and they are disgusted and embarrassed by the protest. … They do not believe the Gibsons are racist.”

One of the witnesses who testified on behalf of the bakery was Clarence “Trey” James, an African American resident of Oberlin who has worked at the store since 2013. When asked if he had seen the Gibsons treat customers or employees in a racist way, he testified, “Never, not even a hint. … Zero evidence of that.” Over the past five years, 40 people have been caught shoplifting at Gibson’s; six were Black.

Eric Gaines, a retired air-traffic controller in town who is African American, testified that he thought the charges of racism against Gibson’s were “preposterous.”

Administration leads charge

The protests began two days after the Nov. 8, 2016, elections in which Donald Trump had been elected. “This has been a difficult few days … because of the fears and concerns that many are feeling in response to the outcome of the presidential elections,” wrote Raimondo and then college President Marvin Krislov in a Nov. 11 letter to faculty and students — as if that somehow justified targeting a small business and smearing its owners as “racists.”

The Gibson’s complaint, backed by trial testimony, described how Raimondo and other college officials, including Tita Reed, assistant to the president, shouted defamatory statements through a bullhorn at the Nov. 10 demonstration outside Gibson’s.

Witnesses testified that college authorities helped reproduce the libelous flyer on college equipment. They supplied demonstrators with pizza, beverages and gloves to stay warm. “Providing refreshments and gloves, the college said, did not amount to aiding and abetting the protests,” a June 14 New York Times article reported. (One can only ask what it did “amount to”!)

David Gibson, writing in USA Today, described how he became convinced, in face of big odds, to press the fight against the wealthy college’s false accusations. He said his 90-year-old father, Allyn, had told him, “‘In my life, I’ve done everything I could to treat people with dignity and respect. And now, nearing the end of my life, I’m going to die being labeled a racist.’”

Support from working people

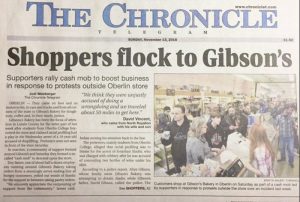

“Without community support, we wouldn’t have won,” Allyn Gibson Jr., told the Militant June 22. “People from the area, from surrounding districts, traveled in to offer their support.”

Solidarity with Gibson’s by working people in the area began two days after the student picket, when large numbers from near and far crowded the store to offer their support by shopping there. An article in the student-run Oberlin Review noted the numbers of “Support Gibson’s” lawn signs sprouting up around Lorain County.”

Attorneys for the college failed to get the trial moved out of Lorain County, where Oberlin is located. They claimed “the jury pool has been poisoned,” by local media coverage of the case and it had a “lack of balanced views.”

Working people in that part of Ohio, like others across large parts of the country, have faced a deep economic crisis, with job cuts in auto, steel and other industries. In 2017 USA Today listed Lorain County as one of the areas that “never recovered from the Great Recession.”

An Oberlin College Student Senate Resolution was carried Nov. 10, 2016, the day of the protests, calling for a boycott of Gibson’s. The Gibson’s complaint states that on or before Nov. 14, Raimondo instructed the director of dining services to tell Bon Appetit Management Company, which supplied the dining hall, to cancel its contract with the bakery. The suspension of the college’s business lasted for two months and began again when the lawsuit was filed. Sales dropped sharply, some 50% since 2016.

When Roger Copeland, a retired Oberlin College professor of theater and dance, wrote a letter to the campus paper criticizing the college’s actions, Raimondo texted another administrator, “F–k him. I’d say unleash the students if I wasn’t convinced this needs to be put behind us.” Unleash the students! Revealing language for an official the college administration insists took part in the protest only to ensure it was “safe and lawful for all.”

Jury’s damage awards

The Lorain County jury on June 7 found the college and Raimondo liable for defamation. It also found the college liable for inflicting intentional emotional distress on the Gibsons, and Raimondo for intentional interference in a business relationship. The jury awarded the bakery owners $44 million in compensatory and punitive damages.

During the trial, the college’s attorney called an “expert” who sought to minimize any possible financial harm to the bakery by dismissing it as being worth only $35,000 — a statement that must have seemed particularly arrogant and galling to those in the courtroom who knew that was less than half the annual tuition, room, board and fees of an Oberlin College student.

The college also sought to poor mouth to the jury, complaining it faces financial difficulties and that a large monetary award to Gibson’s would be hard to meet. Jurors evidently didn’t find this convincing from an institution with a $1 billion endowment, 18 administrators taking home more than $100,000 a year, and salaries of half a million for its president and chief financial officer.

Not a ‘free speech’ issue

Since the verdict, the college administration has sought to counter the decision. Current Oberlin President Carmen Twillie Ambar claims “this is a First Amendment case about whether an institution can be held liable for the speech of its students.” In fact, the Gibson’s complaint targeted not the students or their right to speak and protest, but the defamatory actions of the college and Raimondo, its vice president. And the jury held the college accountable for what its own representatives did, not for either the views or actions of any students.

In a FAQ issued June 19, the college claims no member of its senior leadership participated in the protest, nor did the college “create, endorse or condone” the protest flyer alleging the Gibsons were racist. But Clarence “Trey” James had testified he was working during the protest and could clearly see Raimondo “standing directly in front of the store with a megaphone, orchestrating some of the activities of the students. … She was telling the kids … where to get water, use the restrooms, where to make copies” of the flyer.

The entire case was about the Oberlin College administration’s attitudes of class privilege and entitlement, not freedom of speech. They thought they could defame a small business as racist, with impunity. They never anticipated the Gibson’s determination to fight for the truth and dignity, nor the support they would get from working people and others repelled by the college’s smear campaign. They were wrong on all counts.