SAN FRANCISCO, Calif. — In a blow to artistic and political rights in the name of “political correctness,” the San Francisco School Board voted to destroy the “Life of Washington” mural at George Washington High School here June 25.

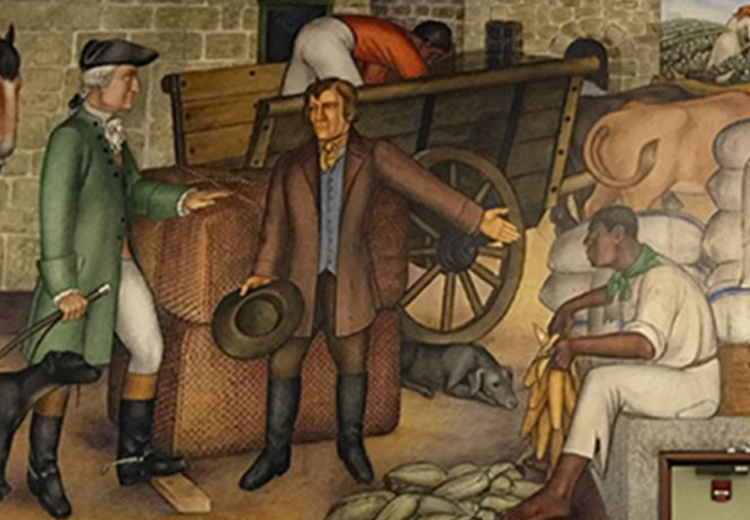

The huge fresco was painted in 1936 by noted muralist Victor Arnautoff, a protégé of Mexican muralist Diego Rivera and member of the Communist Party. Commissioned by the government-funded Works Progress Administration, it has 13 panels and has been part of the lobby of the school for over eight decades.

The week before the vote, a special school board hearing was held where over 150 people debated the proposal to destroy the mural. Those demanding its destruction argued that some of the images make the mural racist and glorify slavery and the genocide of Native Americans.

“Censorship creates precedents that will always come down hardest on the working class, including African American, Latino, Native American and Asian American working people,” said Joel Britton, Socialist Workers candidate for mayor of San Francisco, who spoke and passed out a statement at the meeting.

“Censorship hands a weapon to those who would target the strongest fighters for our class and artists who are our allies,” he said.

Those supporting each side of the debate were given 30 minutes to present their view, with each speaker strictly limited to one minute.

Among the first to speak was Lope Yap Jr., vice president of George Washington High School’s Alumni Association, a group with thousands of members that has fought to save the mural. He pointed to the artistic value of the work and the fact that the artist was an ally of oppressed peoples. “This is history,” he said. “We should learn from history, not cover it up.”

Speakers against censorship noted that the panels described as being racist and demeaning of Native Americans and Black people were precisely those that Arnautoff painted in order to condemn slavery and the U.S. government’s treatment of Native Americans, to puncture myths about Washington that were current in the 1930s.

One panel shows George Washington pointing west over the body of a dead Native American, representing his push for settlement of lands that led to the genocide of native people. Another portrays Black slaves working Washington’s large plantation in Mt. Vernon, Virginia.

Battles over proposed destruction of politically influenced art have marked San Francisco politics before. During the 1950s McCarthyite witch hunt, congressional hearings were held over demands to destroy an extensive series of murals painted in the 1940s by Anton Refregier in the Rincon Annex Post Office. One of those who had recommended Refregier as the artist was Arnautoff.

Refregier was castigated in Congress for painting panels depicting the historic 1934 longshore workers strike and for images that presented Native Americans as “vigorous and strong.” The California American Legion called for the mural’s destruction because they would expose school children who toured the facility to scenes that unfairly slandered “the true history of our state.”

Despite the censorship campaign, the mural was never destroyed.

Debate over Washington High mural

The proposal to destroy the Washington High mural was made by a “Reflection and Action Group” of 13 members that was convened by the Board of Education after several parents complained about the mural’s contents. One of the first to complain was Amy Anderson, a member of the Ahkaamay Mowin tribe, who spoke at the hearing.

“Everything in it is based on people who are white,” Anderson said. “Today is a good day for all of us who are abused in these panels.”

Paloma Flores, director of the San Francisco Unified School District’s Indian Education program and a leader of the campaign to paint over the mural, argued at the hearing that the panel showing the dead Native American should be erased because it causes trauma and pain for Native American students.

“No one has the right to tell us as native people or our young people who walk these halls every day how we feel,” Flores said. “You’re not in our shoes, you don’t feel what they feel unless you are living it.”

Other speakers repeated this, implying that only the views of Native Americans and Black people should be weighed in the decision. One speaker even discounted the views of all those who spoke against censorship, saying they had a “colonizers’ mentality.”

But not all Native Americans at the hearing called for destroying the mural. Robert Tamaka Bailey, an Oklahoma Choctaw and retired PG&E worker, spoke in defense of keeping the mural.

Andrea Morell of the Socialist Workers Party pointed to the broader trend among liberals, including some who call themselves socialists, to attack freedom of speech, freedom of assembly and freedom of artistic expression as a means of opposing what they call “cultural appropriation.”

“Shielding Native American and African American youth by effacing this mural has nothing to do with the fight to eradicate exploitation and racial oppression,” she said. “Instead it undermines that fight.”

“Censorship makes it easier for that weapon to be used by reactionary forces and the government against movements for social change or against the unions, as it inevitably has been and will be again,” she said.