Thank you Silvio for your thoughtful remarks.

And a warm welcome to all of you who are present.

This is an important day for us.

It’s a unique opportunity, using the three books whose covers you see here at the front, to introduce the Socialist Workers Party in the United States to you. An opportunity to convey who we are. To explain where we and our sister Communist Leagues in other countries come from. And to outline our communist course of action within the class struggle in the U.S. and the world.

It may come as a surprise to some of you, but we have never had an opportunity to do that here. Nor have we had three new books that present our course as clearly as these three taken together.

I say “new,” but none of the material in these books, including the introductions, is politically new. It will just seem so to many readers. One of the books — Malcolm X, Black Liberation, and the Road to Workers Power — was published a decade ago. Even that book you will read with new understanding, however. And you will discover new things in its pages when you realize it could not have been written except as a product of The Turn to Industry: Forging a Proletarian Party.

Each of the three books treats the same questions from a different starting point.

Foundation for all three

The Turn to Industry: Forging a Proletarian Party is by Jack Barnes, longtime national secretary of the Socialist Workers Party. It’s the foundation on which the other two are built. Without what we call “the turn to industry,” carried out by the cadres of the Socialist Workers Party beginning in the mid-1970s, the line of march and class clarity captured in the other two books would not have been possible.

Tribunes of the People and the Trade Unions contains writings by communist leaders, from Karl Marx, V.I. Lenin and Leon Trotsky to Farrell Dobbs and Jack Barnes today. Drawing lessons from 175 years of revolutionary struggles by working people, these leaders present our communist continuity. They explain why organizing to strengthen and transform the unions is not only essential to the fighting unity and political striking power of the working class. It is central to building a revolutionary proletarian party as well.

To use Lenin’s words, “tribunes of the people” is simply another name for a proletarian party, a party that “reacts to every manifestation of tyranny and oppression, no matter where it appears.” A party of class-struggle deeds that, at the same time, uses every manifestation of capitalist exploitation and oppression to explain why it is workers and our allies who can and will discover our own capacities, our own worth, as we use our collective strength to take on the bosses over wages and job conditions and begin to realize that those who exploit our labor will never act in our interests.

Malcolm X, Black Liberation, and the Road to Workers Power is also by Jack Barnes. The thread running throughout the book is not only the strength and resilience of the oppressed African American nationality in the United States. It also underscores the vanguard place and weight of workers who are Black in the broad, proletarian-led social and political struggles that have occurred in the U.S., from the Civil War to today. The documented record alone, Barnes says, will “bowl you over.”

Tracing a century and a half of class battles, the book helps us understand how Malcolm X emerged from the rising struggle of African Americans as its most far-sighted leader and became in fact a leader of the entire working class in the U.S. A leader with a revolutionary internationalist perspective.

Nowhere else will you find explained with such clarity why it is only the revolutionary conquest of power by the working class — as you have demonstrated here in Cuba — that will make possible the final battles for Black freedom, and open the way to a world based not on exploitation, violence and racism, but human solidarity. A socialist world.

Books about SWP today

As we prepared together for our presentation today, Silvio remarked to us that he had worked with comrades of the SWP for a year or more. He has read the four books he joined us in presenting last year by former party National Secretary Farrell Dobbs on the union battles led by the party in the 1930s — Teamster Rebellion, Teamster Power, Teamster Politics and Teamster Bureaucracy. Silvio said he thought he knew us a little and was prepared for what he would read in the books we’re presenting today.

But he was still surprised, he said, when he read The Turn to Industry: Forging a Proletarian Party.

“The labor struggles of the 1930s took place 80-90 years ago. They are part of history,” he commented. “But The Turn to Industry is different. It’s about the SWP today. And it’s explained so well.”

Silvio is correct, and I hope it is the main thing you take with you from this discussion. The turn to industry the party carried out at the end of the 1970s and early 1980s is what forged the SWP — and the political course and clarity of its cadres — today.

Throughout the 1960s and early 1970s, the party and its affiliated youth organization, the Young Socialist Alliance, had grown rapidly. We recruited large numbers of new members who had been won to the revolutionary working-class movement as students fighting Jim Crow segregation, North and South.

Many more were won as the party led and organized massive opposition in the streets to Washington’s war against the Vietnamese people. And as we fought to lead the growing women’s liberation movement on a working-class course, as well as fights around many other social issues.

From the day we joined, however, we took it for granted that as the class struggle sharpened, we would organize to get jobs in industry and work to strengthen the trade unions as instruments of class struggle. That we would join in fights for wages and safety on the job, as well as organize with co-workers to carry into the unions political campaigns the party was involved in around social questions of importance to the working class. That we would help mobilize workers in factories, mines and mills to think socially and act politically, as part of the broad struggles advancing in the U.S. at the time.

That was the only course consistent with the entire history of the communist movement we had joined. The only course consistent with everything we had learned from the generations of battle-tested leaders of the working class — James P. Cannon, Ray Dunne, Farrell Dobbs — who recruited and educated us.

Forging a proletarian party

By the mid-1970s, U.S. capital had begun a ferocious drive to break the most powerful unions, including in coal and steel, and to increase their competitive edge over capitalist rivals worldwide. Working-class resistance was mounting. Recognizing the opportunity — and the necessity — to act, the party’s National Committee adopted proposals presented to them in a report by Jack Barnes. The first article in The Turn to Industry is that February 1978 report, “Leading the Party into Industry.”

Most importantly, the party cadre, almost to a person, implemented that report with enthusiasm. It was the moment we had been waiting for.

We had already learned, from our own experiences, what is explained in one of the SWP’s most important documents, adopted on the eve of Washington’s entry into World War II: “We will not succeed . . . in defending the revolutionary proletarian principles of the party from being undermined unless the party is an overwhelmingly proletarian party, composed in its decisive majority of workers in the factories, mines and more.”

That’s what the turn to industry was — and is — about.

By the early 1980s virtually every member of the party, and every nonstudent member of the YSA, was engaged in union and political actions together with other workers in auto plants, steel mills, rail yards, packinghouses, garment shops, textile mills, mines, oil refineries and more. The only cadres not in industry were those assigned to full-time work for the party — on the Militant staff, in our print shop, and a small number who had been elected to national political leadership responsibilities. When comrades were rotated out of those assignments, moreover, they joined one of the party’s union fractions, and others who had been in industry stepped in to relieve them.

Participants in the party’s leadership school, begun in 1980, were chosen on the basis of leadership demonstrated in the turn and its related mass work.

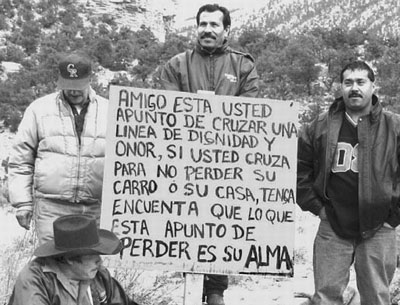

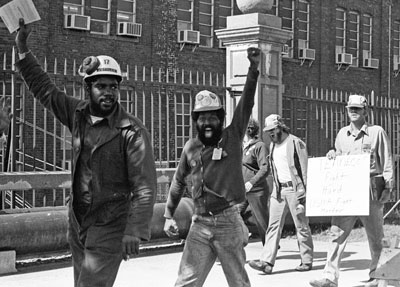

The rich lessons of the first years of the turn — enhanced with a wealth of photos capturing some of the important experiences party cadres were part of — is what The Turn to Industry records.

You’ll be interested to learn that leaders of Cuba’s Union of Young Communists were part of this too. One photo you’ll find in The Turn to Industy is of 21-year-old Kenia Serrano, who more recently served as president of the Cuban Institute for Friendship with the Peoples for some eight years. At the time of the photo she was international relations secretary of the Federation of University Students. It shows her talking with striking United Auto Workers union members in York, Pennsylvania, while she was on a six-week speaking tour in the U.S. in 1995.

Rogelio Polanco, Cuba’s former ambassador to Venezuela and now Dean of the Higher Institute of International Relations, was part of that tour for three weeks as well. In addition to speaking on some 50 college campuses, in 13 states and 28 cities, including Miami, they took part in a dozen trade union and workplace activities, such as meeting the UAW strikers in Pennsylvania and touring a Ford assembly plant in St. Paul, Minnesota.

Combating class collaboration

The political and economic factors that pushed working-class struggles and the labor movement to center stage in the 1970s and ’80s do not exist today. In face of unrelenting attacks by the capitalist class, its government, and its parties — on wages, working conditions and democratic rights — the working class and labor movement have been in retreat for more than two decades. Union membership in privately owned workplaces has plunged from more than 20 percent when the party’s turn to industry began to 6.5 percent today.

What is the reason for the decline of the union movement? Above all, it is the integration of the union officialdom into the imperialist state apparatus, through the two large capitalist parties, the Democrats and Republicans. This is what Trotsky explains so clearly in “Trade Unions in the Epoch of Imperialist Decay,” one of the central articles in Tribunes of the People and the Trade Unions.

The course of the union officialdom today is not one of mobilizing union power to defend the working class. To the contrary, their “strategy” — if such a word can be used to describe it — is to rely on the passage of hoped-for “pro-labor” legislation by capitalist politicians, in return for all-out electoral backing organized and financed by the union apparatus. With few exceptions, that translates into support for the Democratic Party, one of the two imperialist parties.

For these labor misleaders, organizing the unorganized — or waging anything other than choreographed strikes, the outcome of which has already been decided with the bosses behind closed doors before the strike begins — jeopardizes their political alliances. That is, it threatens their own comforts and well-cushioned life style.

The four-decade relentless assault by the U.S. capitalist class will continue until it meets stiff resistance from sections of the working class. But the laws of capital have not changed. Sooner or later the bosses will try to push too far, sustained battles will erupt, and the retreat will end.

We can already say the opportunities and political openness to the course of action we present — in all our work on the job and in working-class neighborhoods, in both cities and countryside — has seldom been greater. Openness to the Militant, to books like these published by Pathfinder Press, to SWP election campaigns like the nationwide presidential ticket of Alyson Kennedy and Malcolm Jarrett we’re running in 2020.

And that openness is greatest precisely among those whom the rulers and their privileged servants of the professional and upper middle classes demean as “deplorables,” “criminals,” “illegals” or just plain “trash.”

For us, they are our people. We come from them. We are part of them.

We are confident, moreover, that whenever the class struggle does sharpen, the SWP will be ready. Because for us, the turn to industry was never a shortcut. It was never an ultraleft gimmick, as it was in the 1960s and ’70s for many Maoist groups and other leftist parties in the U.S. and elsewhere around the world.

For the SWP, the turn was simply the extension of the working-class line of march we were already on. It was what we had learned from the party cadres who had led working-class battles in the 1930s. And from those who in 1919 had helped found the American section of the newly organized Communist International.

It was what we had already learned ourselves from the two most important battles that shaped our generations.

One of those battles, one with a truly revolutionary character, was the mass movement led by Black proletarian cadres that brought down the entire edifice of Jim Crow racial segregation. For the better part of a century, it had been the single greatest barrier to the fighting unity of the U.S. working class.

The second was what we learned from Cuba’s victorious socialist revolution and our battle to defend it.

That’s the point I will end on.

Cuba and American revolution

For “the turn generations” of the SWP, the Cuban Revolution has always been “our revolution.” In much the same way the October Revolution in Russia was the decisive historical event that shaped the trajectory of the founders of the communist movement in the U.S. and elsewhere. We studied and absorbed the lessons of October too, including lessons of the Stalinist counterrevolution against Lenin’s internationalist course, for which the working class has paid an enormous price the world over.

But the Cuban Revolution was not only something we studied. It was something we lived.

Jack Barnes, the principal author of these three books, often recounts the importance of the time he spent in Cuba in the summer of 1960, as working people there were carrying out the sweeping nationalization of U.S.-owned factories, utilities and other imperialist holdings. Everyone already knew a U.S.-organized invasion was coming. It was only a matter of when, and the militias were urgently training to meet it. “Learn in the morning. Teach in the afternoon” was the watchword. Jack’s response was that he wanted to stay to fight against the inevitable assault.

One of the Cubans Jack had come to respect most — an officer of the Rebel Army — told him, “No. That’s not the help we need. We’ll meet the invasion whenever it comes and defeat it. The important thing is for you to go back to the United States and organize to make a revolution there, like we’re doing here.”

And that is what the author of these books did. He went back to the U.S. and joined the party whose deeds — as well as words — proved its cadres had always been on that class trajectory. The only party for whom emulating the Cuban Revolution already had meaning in our day-to-day political lives.

That party is the Socialist Workers Party. And we exist today thanks to the Cuban Revolution and thanks to the turn to industry and course of action you will encounter in these three books.