The Spanish-language edition of Making History: Interviews With Four Generals of Cuba’s Revolutionary Armed Forces by Enrique Carreras, Harry Villegas, José Ramón Fernández and Néstor López Cuba is one of Pathfinder’s Books of the Month for May. The first piece below is from an interview with Carreras, about how he was won to a lifetime of revolutionary activity. Before the popular triumph of the Cuban Revolution, Carreras was an air force officer who had trained in the U.S. during the Second World War. He opposed the U.S.-backed coup by Fulgencio Batista in 1952 and joined the revolutionary movement led by Fidel Castro. The excerpt is from “War of the Entire People Is the Foundation of Our Defense.” The second piece is from his biography that accompanies it. Copyright © 1999 by Pathfinder Press. Reprinted by permission.

ENRIQUE CARRERAS: In the course of World War II, while in the United States, I observed many things. For example, I had never before seen women occupying posts previously held only by men, or training alongside men. At the time of the war there was still a lot of machismo in Cuba. We did not want to see women in the streets alone going to the store, much less working outside the home, even in the fields. The revolution has been eliminating all that machismo.

At Kelly Field I saw women training as pilots and gunners for ferrying B-25 bombers from bases in the United States to Canada, and sometimes even to Britain.

That was my first experience in the United States. What I learned there — the training I received as a combat pilot — I subsequently taught to the pilots we trained in the early years of the revolution, including those who fought at Girón. The same tactics the U.S.-organized forces used in attacking Cuba, we applied against them. But we were defending a just cause, while they were coming to reconquer what they had lost. So we’re not talking about moral equivalents. …

[By 1955], the political situation in Cuba was very bad. In March 1952 Batista had seized power in a military coup.

On July 26, 1953, the Moncada army garrison was attacked. This assault was the motor that drove the revolution forward, even though it failed militarily. The attackers were not able to take the garrison, distribute arms to the people, and open the offensive against Batista — which is what they intended to do. Some of the combatants were murdered right there in the Moncada on Batista’s orders. Others were convicted and sent to prison, serving their sentences on the Isle of Pines. …

Like a number of other soldiers and officers in the armed forces, I was opposed to the Batista dictatorship. …

I was arrested, tortured, court-martialed, and dishonorably discharged by the tyranny. They initially asked for the death penalty. I served time in various prisons, including La Cabaña. Then they sent me to the Isle of Pines, where I began to get to know the revolutionaries who were imprisoned there. …

[C]ompañeros from the July 26 Movement who had come on the Granma were imprisoned there. Young people from the Revolutionary Directorate and people from the Popular Socialist Party were also there. All of them were there together.

The political views I held at that time came from the army. Anticommunism and hatred for the Soviet Union had been drummed into my head. That’s what they taught us in the academies. I didn’t know what a communist was, but everything I had heard about them was bad. I was influenced by all that propaganda.

While serving time in prison, however, I got to know all of them — [Jesús] Chucho Montané and other compañeros from the Granma; Lionel Soto; the compañeros from the Directorate.

By the time the revolution triumphed, I was no longer the anticommunist I had been before. I had become a progressive, a revolutionary. And then I witnessed all the acts of aggression organized by the U.S. government in the early years. I came to understand how wrong everything they taught me had been. I learned in the course of the struggle, and that’s the best way.

❖

After the revolution’s triumph at the opening of 1959, Carreras … was assigned by Fidel Castro to train a corps of pilots.

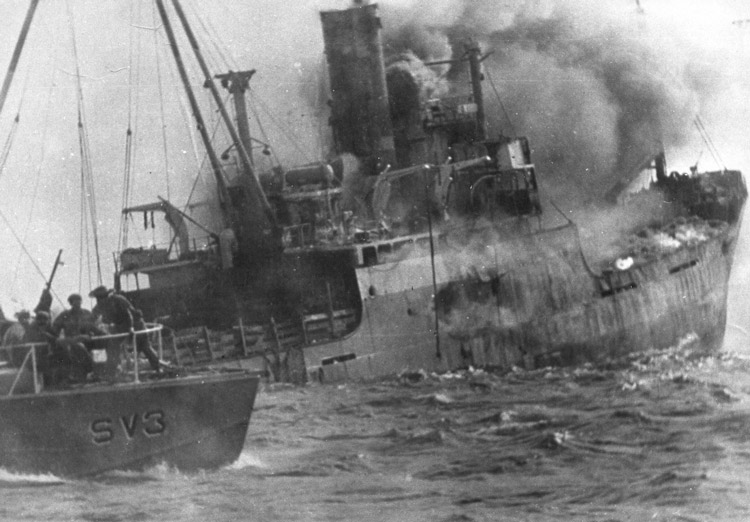

In April 1961, at the Bay of Pigs, the day they were preparing for arrived. As a prelude to the U.S.-backed invasion, the air force bases in San Antonio de los Baños, Santiago de Cuba, and Ciudad Libertad in Havana were bombed on April 15 by CIA-trained counterrevolutionaries flying planes whose markings had been painted to appear to be those of the Revolutionary Armed Forces (FAR). Seven people were killed and fifty-three wounded. Cuba’s few existing planes had been dispersed on Castro’s instructions. Only two were destroyed.

The following day, at a mass rally to honor the victims of the attack and to mobilize the entire population for the coming war, Fidel Castro proclaimed for the first time the socialist character of the Cuban revolution.

Expecting an invasion at any moment, the commander in chief ordered Carreras and the other pilots to remain by their planes at all times. They slept on the runway beneath the wings of their aircraft.

On April 17, at 4:45 a.m., Carreras was urgently called to the telephone. Fidel Castro was on the line. A mercenary army was invading Cuba at Girón Beach on the Bay of Pigs. Castro issued immediate orders:

“Carreras, there’s a landing taking place at Playa Girón. Take off right away and get there before dawn. Sink the ships transporting the troops and don’t let them get away. Understood?”

“Understood, commander.”

Over the next seventy-two hours, the air squadron Carreras headed, consisting of ten pilots and eight dilapidated planes inherited from the armed forces of the dictatorship, was decisive in defeating the U.S.-organized invasion. The Cuban planes brought down nine B-26 bombers flown by the counter-revolutionaries and U.S. pilots, sank a number of their ships, and hounded the mercenary troops on the ground. Carreras himself shot down two aircraft, and the fighter plane he was flying was hit twice by enemy fire.