More than two weeks after Minneapolis cops brutally killed George Floyd, protests on an unprecedented scale continue to sweep the world. From big cities to rural towns in the U.S. and elsewhere, hundreds of thousands, if not millions, have joined the protests — most for the first time in their lives — and have focused attention on countless other cases of police brutality.

The widespread protests forced prosecutors to indict the four cops involved in killing Floyd and to lodge more weighty charges against Derek Chauvin, who pressed his knee down on the handcuffed man’s neck for nearly nine minutes, from third-degree to second-degree murder.

The actions boosted the fight to prosecute the cops who shot dead Breonna Taylor, an emergency room technician, during a midnight no-knock raid on her apartment in Louisville, Kentucky, March 13. The cops who burst into Taylor’s home, spraying the bed where she slept with bullets, are still on paid desk duty, while an “investigation” is underway.

On June 5, which would have been Taylor’s 27th birthday, calls for the prosecution of the cops who killed her were heard at many of the actions.

Hundreds rallied at the Brunswick courthouse in Georgia June 4, following a hearing for the three white vigilantes charged with the February killing of Ahmaud Arbery, a Black youth slain while he was jogging.

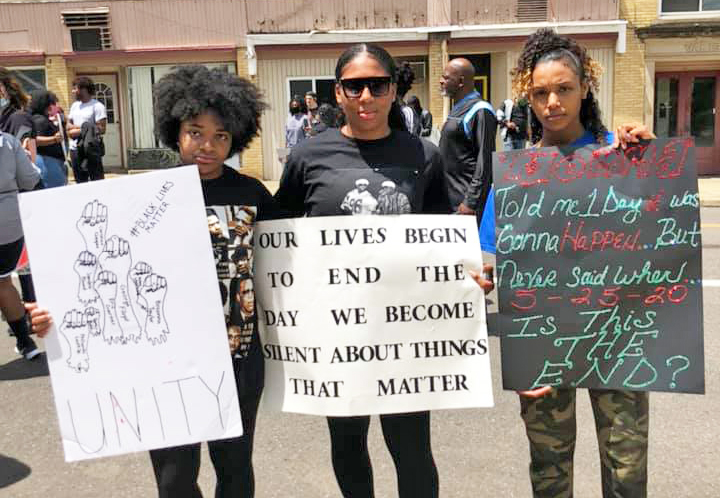

In a sign of the depth of the outrage over police killings, several hundred demonstrations have taken place in small towns and rural areas across the U.S. This shows the ongoing impact of the fight for Black rights in the 1950s and ’60s that overturned Jim Crow segregation in the South and advanced the fight against racism across the country and around the world. That fight, led by Black workers, transformed social relations in the country, making it more possible for workers of all nationalities to work, live and fight together.

Protesters at today’s actions are young and old, Black, Latino, Caucasian and Asian — proof that there is less racism than ever among working people. The real source of racist discrimination and cop brutality is the functioning of capitalism, which seeks to foster divisions among working people, to pit them against each other and divert them from their real enemy.

Throughout the day on June 8 people attended a wake for Floyd at the Fountain of Praise Church in Houston, where he was brought up. “I owe my condolences to George Floyd,” Martin Dailey told Alyson Kennedy, Socialist Workers Party candidate for president, at the event. “I am fighting a firing from my job as an operator from a PVC chemical plant in Freeport, Texas, because of discrimination.”

The massive protests take place as working people also confront growing assaults on our jobs, wages and working conditions.

Rural Kentucky an ‘ally’

More than 100 mostly young workers joined a protest in Harlan, Kentucky, June 2, organized by high school student and Arby’s worker Bree Carr. Harlan County, which is 96% Caucasian, has a long history of strikes and protests by coal miners.

Carr told the Harlan Enterprise that she’d “been thinking how much I want to do something.” So she put out a flyer and recruited others she met at Walmart to help organize the protest.

Carr told the Harlan Enterprise that she’d “been thinking how much I want to do something.” So she put out a flyer and recruited others she met at Walmart to help organize the protest.

The turnout was better than she expected, and passing cars honked in support. “Deep within rural Appalachia, especially in southeastern Kentucky, people look upon us like we ignore issues that are happening and like we’re uneducated,” Carr told the press. “My idea was to show people of color who are struggling right now all over the country that there are people in this rural place that are allies.”

There have been similar protests in Hazard, Pikeville, Paintsville and other smaller towns across Kentucky.

Over 100 people joined a rally in Havre, Montana, a farm town of 9,700. The protest was organized by Melody Bernard, a Chippewa Creek tribal member. One participant was Dorian Miles, a young Black man, who moved there just five months ago to play football for Montana State University.

He was blown away. “A SMALL town of predominantly older white Americans stood with me to protest the wrongdoings at the hands of police EVERYWHERE,” he wrote to friends on Facebook.

Two young Black women, Ande Green and Essence Blue, put out a flyer announcing a protest in Alliance, Ohio, population 21,616, 80% Caucasian. “We didn’t know what to expect,” Green told The Associated Press. “But over 300 people showed up.”

Green also put her finger on the reality of the working class in the U.S. “These small towns matter because it’s a lot of small towns,” she said. “All of these small towns coming together, it’s what we need to make a change.”

The blows of today’s capitalist social crisis hit hard on the countryside with hospitals closing, jobs gone and social aid programs slashed.

‘People’s thinking has evolved’

What happened to George Floyd can’t be accepted as the “status quo,” Emma Boateng told a protest of 800 in Old Bridge, New Jersey, a majority Caucasian town of 24,000. She was part of a contingent of Black high school students on the march. “We are here to build our community, not burn it,” she said.

“My grandmother grew up in the South and had to sit on the back of the bus,” high school student Zora Dancy told Candace Wagner, the SWP’s candidate for U.S. Congress in New Jersey’s 8th District, at the march. “She joined the fight to change that. And now here I am still fighting.”

During the first week after Floyd was killed, many of the U.S. protests — especially in larger cities — were marred by looting and in some cases violent attacks on police stations. Some were carried out by provocateurs on the march. Most were organized by gangs or frustrated youth, targeting jewelry, electronics, shoe as well as grocery stores and other large and small businesses, many already reeling from the government-imposed coronavirus shutdowns.

Many of the attacks on cops and police stations were carried out by antifa groups and other middle-class radicals. All of these weakened the protests, putting barriers in the way of involving more working people who backed the aims of the actions.

Government authorities took advantage of the violent acts to go after democratic and political rights.

In New York, Mayor Bill de Blasio imposed a weeklong 8 p.m. to 5 a.m. curfew. Some 2,000 people had been arrested as of June 5 for curfew violations, “unlawful assembly,” disorderly conduct and resisting arrest. But with large peaceful demonstrations continuing past curfew every day, it was lifted.

‘New York Times’ defends looting

While most working people oppose the pillaging, the New York Times took the lead in justifying it. “Violence is when an agent of the state kneels on a man’s neck until all of the life is leached out of his body. Destroying property, which can be replaced, is not violence,” Pulitzer Prize winning Times reporter Nikole Hannah-Jones claimed on CBS News June 2. “To use the same language to describe those two things is not moral.”

To Hannah-Jones, the people who own now-destroyed small businesses, the workers out of a job because the stores they worked at lie in ruins, and the working people who depend on them to shop — often their only source of basic necessities — are of no concern. She just sees “property.”

Areas hard hit by looting include the Minneapolis neighborhoods near where Floyd was killed, with many stores destroyed.

A two-block area there has been roped off and become a center of discussion and protest. More than a dozen volunteer stands — organized by individuals and church groups — provide free hot meals and water all day and late into the evening to neighborhood residents and thousands streaming in to visit the memorial set up to Floyd.

Several places donate food, diapers and other supplies that are now harder to get because of shuttered or destroyed stores.

Postal workers union joins protests

On June 7, 75 members of the postal workers union and some bus drivers marched into the area carrying a banner that read “Postal Workers Demand Justice for George Floyd.” They had started out at the remains of the nearby post office that was gutted by fire during looting the week before.

Many unions and national farmers organizations have spoken out against the killing. More organized labor participation would significantly strengthen the fight against police brutality. But even in its absence, many protesters successfully pushed back looters and provocateurs. Protesters in Spokane, Washington — like in many other cities — formed a human chain to prevent the looting of a Nike store June 1.

Organizers of many of the thousands of protests around the country also made clear that looting and violence would not be tolerated, helping reduce provocative actions.

The protests have a deep impact. Todd Winn, a U.S. Marine, joined a June 5 protest in Salt Lake City in uniform for three hours holding a sign that said, “Justice for George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Tamir Rice, Countless Others.” Unlike the cops, workers and farmers in the armed forces can and are being won to the side of working-class struggles.

International protests

Protests against police brutality and racism have spread to more than 40 countries, often centered around cases of brutality perpetrated by the cops there, including in Australia (see article on this page), Canada, France, Iran, Israel, Italy, Kenya, Germany, Spain, Thailand, the U.K. and many more.

At June 6 protests in major cities across Brazil, marches carried “Black Lives Matter” banners emblazoned with the name of João Pedro Matos Pinto, 14, who was gunned down by cops in a suburb of Rio de Janeiro. After storming the youth’s home, throwing a grenade inside and spraying it with bullets, the police claimed it was an accident.

“Now is the time to stand up and take part,” Will Goodlake told Militant worker-correspondents at a protest of thousands marching to the U.S. Embassy in London.

These actions show the potential for working people in their millions to unite and organize against police brutality, acts of racist discrimination, and all the iniquities rooted in capitalist exploitation and oppression.