The Spanish edition of Che Guevara Talks to Young People is one of Pathfinder’s Books of the Month for September. After joining Fidel Castro’s July 26 Movement, Ernesto Che Guevara, the heroic Argentinian-born revolutionary, helped to lead the first socialist revolution in the Americas and initiate a renewal of Marxism. A central leader of the revolutionary government from 1959, he was also a leading Cuban representative abroad. From 1965 he led Cuban internationalist fighters in joining revolutionary struggles in the Congo and then Bolivia. Wounded and captured by the Bolivian army on Oct. 8, 1967, he was murdered the next day. The excerpt is from “Youth Must March in the Vanguard,” a speech Che gave as Minister of Industry at a seminar on youth and the revolution, May 9, 1964. Copyright © 2000. Reprinted by permission of Pathfinder Press.

BY ERNESTO CHE GUEVARA

In Cuba the ideology of the old ruling classes maintains its presence through the consciousness of individuals, as I indicated earlier. In addition, it remains present because it is constantly being exported from the United States — the organizing center of world reaction — which physically exports saboteurs, bandits, propagandists of all sorts, and whose constant broadcasts reach the entire national territory with the exception of Havana.

In other words, the Cuban people come in permanent contact with imperialist ideology. This is then repackaged here in Cuba by propaganda outfits scientifically organized with the goal of projecting the dark side of our system, which necessarily has dark sides because we are in a transitional period and because those of us who have led the revolution up to now were not professional economists and politicians with a lot of experience, backed by an entire staff.

At the same time, they promote the most dazzling and fetishistic features of capitalism. This is all introduced into the country, and sometimes it finds an echo in the subconscious of many people. It awakens latent feelings that had barely been touched owing to the speed of the process, to the huge number of emotional salvos we have had to fire to defend our revolution — where the word “revolution” has merged with the word “homeland,” has merged with defense of every single one of our interests. These are the most sacred of all things for every individual, regardless of class background. …

The main way the youth must show the way forward is precisely through being the vanguard in each of the areas of work they participate in.

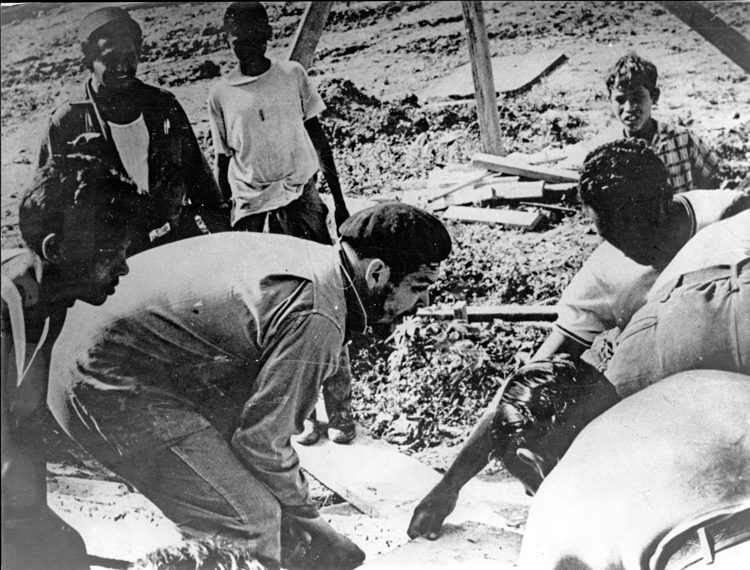

This is why we have often had certain little problems with the youth: that they weren’t cutting all the sugarcane they should, that they weren’t doing as much voluntary labor as they should. In short, it is impossible to lead with theories alone; and much less can there be an army composed only of generals. An army can have one general, maybe several generals and one commander in chief if it is very large. But if there’s no one to go into the battlefield, there’s no army. And if the army in the field isn’t being led by those who have gone into the field themselves, who’ve gone to the front, then such an army is no good. One of the attributes of our Rebel Army was that the men promoted to lieutenant, captain, or commander — the only three ranks we had in the Rebel Army — were those whose personal qualities had distinguished them on the field of battle. …

So the technological revolution must have a class content, a socialist content. And for this to happen, there must be a transformation of the youth so that they become a genuine motor force. In other words, all the bad habits of the old, dead society must be eliminated. One cannot think about a technological revolution without at the same time thinking about a communist attitude toward work. This is extremely important. We cannot speak of a socialist technological revolution if there is not a communist attitude toward work.

This is simply the reflection in Cuba of the technological revolution taking place as a result of the most recent scientific inventions and discoveries. These are things that cannot be separated. And a communist attitude toward work consists of changes taking place in an individual’s consciousness, changes that naturally take a long time. We cannot expect that changes of this sort will be completed within a short period, during which work will continue to have the character it has now — a compulsory social obligation — before being transformed into a social necessity. In other words, this transformation — the technological revolution — presents the opportunity to get closer to what interests you most in life, your work, your research, your studies of every type. And one’s attitude toward this work will be something totally new. Work will be what Sunday is now — not the Sunday when you cut cane, but the Sunday when you don’t cut cane. In other words, work will be seen as a necessity, not something compelled by sanctions.

But achieving that requires a long process, a process tied to the creation of habits acquired through voluntary work. Why do we emphasize voluntary work so much? Economically it means practically nothing. Even the volunteers who cut cane — which is the most important task from an economic point of view — don’t accomplish much.

A volunteer cutter from this ministry cuts only a fourth or a fifth of what a cane cutter who has been doing this his whole life does. It has economic importance today because of the shortage of labor. It is also important today because these individuals are giving a part of their lives to society without expecting anything in return, without expecting any kind of payment, simply fulfilling a duty to society. This is the first step in transforming work into what it will eventually become, as a result of the advance of technology, the advance of production, and the advance of the relations of production: an activity of a higher level, a social necessity. …

Today we have begun a process of, let us say, politicizing this ministry. The Ministry of Industry is really cold, a very bureaucratic place, a nest of nit-picking bureaucrats and bores, from the minister on down, who are constantly tackling concrete tasks in order to search for new relationships and new attitudes.