U.S. government officials and the big-business media are once again resorting to timeworn slanders that the Cuban government is a “dictatorship” following Cuban authorities stopping a Nov. 26 protest action in Havana by opponents of the Cuban Revolution who call themselves “independent artists.”

The fact is the Cuban Revolution has a proud 60-year record fostering development of book publishing, film, music, and artistic creation, expanding access to culture and education among millions of people in city and countryside.

Cuban authorities had evicted from their headquarters and briefly detained a group of 14 members of the so-called San Isidro Movement, an anti-government group. They had been on a hunger strike against the detention of Denis Solís, one of its members, who presents himself as a rap artist. He was found guilty by a Cuban court of contempt of authority for insulting and threatening bodily harm to a police officer in the line of duty and sentenced to eight months in prison.

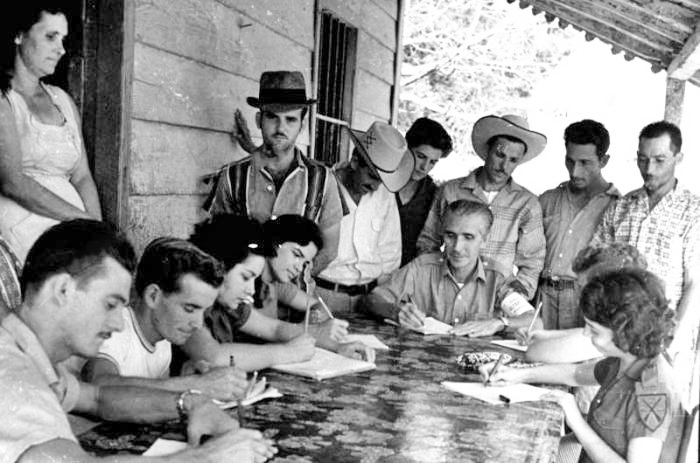

On Nov. 27, some 200 artists, writers and students gathered outside the Ministry of Culture in Havana to voice concerns over the eviction, and to discuss freedom of expression. Vice Minister of Culture Fernando Rojas and representatives of cultural and artist organizations met for four hours with 30 of the demonstrators, including from the San Isidro group, and agreed to more discussions.

Most of the participants were “influenced by the atmosphere created on social networks. Few knew what actually happened at San Isidro or who was involved,” wrote Abel Prieto in the Cuban daily Granma Dec. 4. Prieto is director of Casa de las Américas, a renowned Cuban cultural institution and publisher. He had earlier served as president of the Union of Writers and Artists of Cuba (UNEAC), and was minister of culture for many years. “I think they honestly wanted to have a dialogue.”

‘An operation against the revolution’

“A minority participated with full awareness in an operation against the revolution,” Prieto said. “Their only interest in ‘dialogue’ was to turn it into news, into a show, and score it as a victory. Some needed to justify the money they are paid.”

“The cultural policy of the revolution has opened a wide and unprejudiced space for creators to work in total freedom,” Prieto said, and Cuba’s cultural institutions, while having made some mistakes, “are open to frank discussion with artists and writers.”

As part of their decadeslong economic and political efforts to destroy the revolution in Cuba — under both Democratic and Republican administrations — the U.S. capitalist rulers have promoted and provided funds for individuals and groups that carry out anti-government activity under the banner of defending artistic and intellectual freedom.

Cuban television has shown documentary footage of participants in the protest being contacted by opponents of the Cuban Revolution in the U.S., inciting them to carry out acts of vandalism. It played videos of U.S. officials meeting with members of the San Isidro group.

On Nov. 28 Cuba’s foreign ministry called in U.S. Chargé d’Affairs Timothy Zuñiga-Brown, to protest Washington’s “grave interference in Cuba’s internal affairs.” In reply, Zuñiga-Brown said he would continue his contacts with opponents of the Cuban government and revolution.

Secretary of State Mike Pompeo; Jake Sullivan, President-elect Joe Biden’s pick for National Security Adviser; and other Democratic and Republican politicians have joined to use this provocation to slander the Cuban Revolution.

Dozens of opponents of the Cuban Revolution held a rally in Miami Nov. 28 to support the San Isidro provocation. Small actions were also held that day in New York and five days later in Washington, D.C. Alex Otaola, a self-described YouTube “influencer” and main organizer of the action in Miami, calls on the U.S. government to further tighten economic sanctions against Cuba and for “free enterprise” there.

Dialogue within the revolution

Representatives of the Cuban Ministry of Culture, leaders of UNEAC, and the Saíz Brothers Association, a group of young Cuban artists, held a follow-up meeting Dec. 5 with dozens of artists and writers, including participants in the Nov. 27 demonstration.

But in response to further provocative actions by the San Isidro group, the Cuban ministry announced the day before that it would not meet with individuals who have had direct contact and receive financial support from the U.S. government, or with media outlets that receive funds from U.S. government agencies.

Seeking to promote opposition to the Cuban Revolution, San Isidro group leaders have focused on Decree-Law 349, which would require a government-issued license for the sale of artwork and performances by self-employed artists and musicians. The law also bars art or music with pornographic, racist, “sexist, vulgar and obscene” content, as well as “using patriotic symbols in a way that is contrary to law.”

Cuba’s Council of State adopted the legislation as part of efforts to regulate the private art market in Cuba, which has grown over the past two decades.

Decree 349 generated widespread debate among Cuban artists, both for and against. Its critics, including supporters of the revolution, expressed concern that it would be applied too administratively and could lead to censorship over artistic expression. Enforcement of the law has been postponed to allow further discussion and changes to address these concerns, and has not been implemented.

“The revolution created a massive and eager public for arts and letters,” Prieto wrote. “It also gave space to the most genuine and historically discriminated against expressions of popular traditions and to the most audacious efforts in various artistic genres.”

While some artists and performers have genuine concerns about how best to develop art in Cuba, and are engaged in discussion and debate as part of strengthening the gains of the revolution, groups like San Isidro seek to use these grievances to aid U.S. imperialism to undermine the revolution.

“It’s necessary to clearly separate the comic-strip actions of the marginal elements of San Isidro from what actually happened at the Ministry of Culture,” said Prieto, referring to the Nov. 27 action. “Among the latter, there were valuable young people who must be listened to.”

“Any artistic creator who approaches Cuban institutions with legitimate objectives will find representatives willing to listen and provide support,” he said. “With fakes and frauds there is no possible dialogue.”