Below is an excerpt from The Bolivian Diary of Ernesto Che Guevara, one of Pathfinder’s Books of the Month for September. The diary recounts the political and military campaign Argentine-born Guevara, a leader of Cuba’s socialist revolution, led in 1966-67 to forge a fighting movement of workers and peasants in Bolivia. The aim was to join the battle for land and national sovereignty there and open the road to socialist revolution on the South American continent.

Reprinted below is Guevara’s April 1, 1965, parting letter to Cuban President Fidel Castro. He explains his decision to resign all his government posts and responsibilities in Cuba in order to pursue internationalist missions abroad. Shortly afterwards he departed for the Congo (today Democratic Republic of the Congo), where he spent six months leading volunteers from Cuba fighting beside combatants of the anti-imperialist movement founded by murdered independence leader Patrice Lumumba.

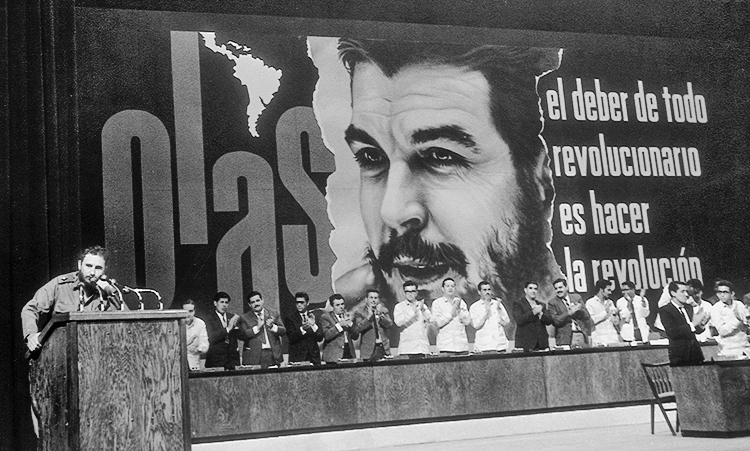

Che’s letter was read aloud by Fidel on Oct. 3, 1965, during a televised speech at the close of the founding meeting of the Communist Party of Cuba. Copyright © 1994 by Pathfinder Press. Reprinted by permission.

Havana

Year of Agriculture

Fidel:

At this moment I remember many things — when I met you in María Antonia’s house, when you proposed I come along, all the tensions involved in the preparations.1 One day they came by and asked who should be notified in case of death, and the real possibility of it struck us all. Later we knew it was true, that in a revolution one wins or dies (if it is a real one). Many comrades fell along the way to victory.

Today everything has a less dramatic tone, because we are more mature, but the event repeats itself. I feel that I have fulfilled the part of my duty that tied me to the Cuban revolution in its territory, and I say farewell to you, to the comrades, to your people, who now are mine.

I formally resign my positions in the leadership of the party, my post as minister, my rank of commander, and my Cuban citizenship. Nothing legal binds me to Cuba. The only ties are of another nature — those that cannot be broken as can appointments to posts.

Reviewing my past life, I believe I have worked with sufficient integrity and dedication to consolidate the revolutionary triumph. My only serious failing was not having had more confidence in you from the first moments in the Sierra Maestra, and not having understood quickly enough your qualities as a leader and a revolutionary.

I have lived magnificent days, and at your side I felt the pride of belonging to our people in the brilliant yet sad days of the Caribbean crisis.2 Seldom has a statesman been more brilliant than you were in those days. I am also proud of having followed you without hesitation, of having identified with your way of thinking and of seeing and appraising dangers and principles.

Other nations of the world summon my modest efforts of assistance. I can do that which is denied you owing to your responsibility at the head of Cuba, and the time has come for us to part.

You should know that I do so with a mixture of joy and sorrow. I leave here the purest of my hopes as a builder and the dearest of those I hold dear. And I leave a people who received me as a son. That wounds a part of my spirit. I carry to new battlefronts the faith that you taught me, the revolutionary spirit of my people, the feeling of fulfilling the most sacred of duties: to fight against imperialism wherever one may be. This is a source of strength, and more than heals the deepest of wounds.

I state once more that I free Cuba from all responsibility, except that which stems from its example. If my final hour finds me under other skies, my last thought will be of this people and especially of you. I am grateful for your teaching and your example, to which I shall try to be faithful up to the final consequences of my acts.

I have always been identified with the foreign policy of our revolution, and I continue to be. Wherever I am, I will feel the responsibility of being a Cuban revolutionary, and I shall behave as such. I am not sorry that I leave nothing material to my wife and children; I am happy it is that way. I ask nothing for them, as the state will provide them with enough to live on and receive an education.

I would have many things to say to you and to our people, but I feel they are unnecessary. Words cannot express what I would like them to, and there is no point in scribbling pages.

Hasta la victoria siempre! [Ever onward to victory!]

Patria o muerte! [Homeland or death!]

I embrace you with all my revolutionary fervor.

Che

- Guevara and Castro met in Mexico in July-August 1955, at the home of Cuban revolutionary María Antonia González. Guevara became one of the first recruits to the revolutionary expedition Castro was planning, which sailed for Cuba in November 1956 aboard the Granma.

- A reference to the October 1962 crisis when President John F. Kennedy demanded removal of Soviet nuclear missiles installed in Cuba following the signing of a mutual defense agreement between the Soviet and Cuban governments. Washington ordered a total naval blockade of Cuba, stepped up preparations for its coming invasion of the island, and placed U.S. armed forces on nuclear alert. Cuban workers and farmers responded by mobilizing massively in defense of the revolution. Following an exchange of communications between Moscow and Washington, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev decided to remove the missiles, without consulting the Cuban government.