On Sept. 7 President Joseph Biden signed off on extending the U.S. embargo of Cuba for another year under the capitalist rulers’ Trading With the Enemy Act. This is no surprise since every president — Democrat and Republican alike — has done the same since 1962. Biden, like his predecessors, views Cuba’s socialist revolution as the most serious challenge to U.S. imperialism in the world.

All those who oppose U.S. aggression against Cuba today can learn valuable lessons from the work of chapters of the Fair Play for Cuba Committee organized across the country during the early years of the revolution.

Soon after working people in Cuba, led by Fidel Castro and the July 26 Movement, overthrew the U.S.-backed dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista in 1959, the U.S. government put their revolution in its gun-sights.

Washington organized counterrevolutionaries to sabotage industry and assassinate literacy volunteers, spread lies about the revolution and prepared an invasion. What the U.S. capitalist rulers most feared was that working people in Latin America and elsewhere would emulate the Cuban Revolution.

But working people, participants in the rapidly expanding fight against Jim Crow segregation, young people, journalists and others went to Cuba to see the revolution for themselves. Inspired by what Cuba’s workers and farmers were doing and becoming, many were determined to get out their story on return to the U.S.

Rapid growth of Fair Play for Cuba

On April 6, 1960, the New York Times printed a full-page ad, initiated by journalist Robert Taber, who visited Cuba after the overthrow of Batista, calling for the creation of committees to promote a fair hearing for the Cuban Revolution. The ad was signed by prominent artists and writers, including Simone de Beauvoir, Jean-Paul Sartre, Norman Mailer, Truman Capote and James Baldwin, as well as Black rights fighters like Robert F. Williams.

Before long chapters were being organized across the country, bringing together people from a wide variety of political views, but united in opposition to Washington’s attacks. This included members of the Socialist Workers Party and the Communist Party. Within six months the Fair Play for Cuba Committee had 7,000 members in 27 chapters and student councils on 40 college campuses.

The committees organized picket lines, rallies, debates and forums to get out the truth about the revolution unfolding in Cuba and protest U.S. aggression. A rally in New York City Oct. 20, 1960, drew 1,500 people to demand “U.S. Hands Off Cuba.”

The next month 400 people attended a Fair Play-sponsored meeting in Harlem where they heard two recent visitors to Cuba — William Worthy, an Afro-American journalist at the New York Post, and Robert F. Williams, well known for leading a fight to free two Black youth, 7 and 9 years old, who had been jailed for kissing a white girl in North Carolina. Top NAACP leaders later removed Williams as president of its chapter in Monroe, North Carolina, for organizing fellow Black veterans into armed self-defense of their community against racist thugs.

“The same people who are our oppressors in the South,” Williams told the crowd, “are the first to say ‘overthrow Castro.’ They try to make us believe that when Castro takes over the big corporations he has taken something from us.” Can you imagine, he said, a Black woman working in a kitchen for $10 a week being worried that Castro is “taking property from us.”

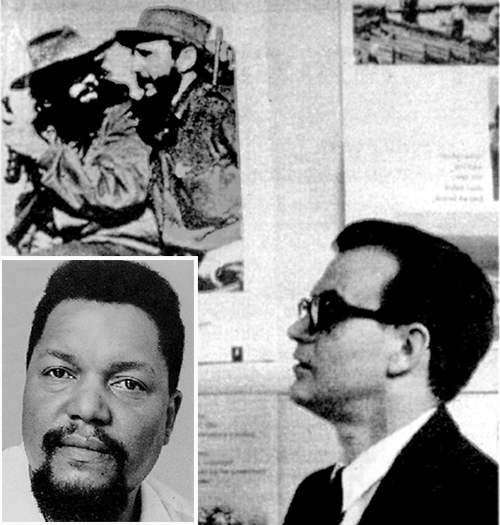

In 1961 Williams, who earlier had worked in the auto factories in Detroit, and Ed Shaw, Midwest organizer of the Fair Play for Cuba Committee, as well as a leader of the Socialist Workers Party and a union typesetter, went on a nationwide speaking tour talking about the Cuban Revolution and the struggle for Black rights.

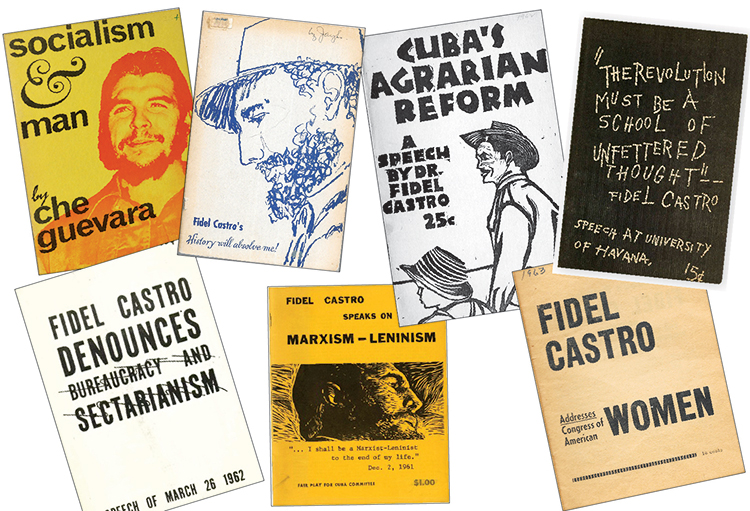

The committee published dozens of inexpensive pamphlets, both eyewitness accounts of the unfolding socialist revolution and speeches by its central leaders.

Among the titles: Cuba’s Agrarian Reform: A Speech by Dr. Fidel Castro; Against Bureaucracy and Sectarianism by Castro; The Revolution Must Be a School of Unfettered Thought by Castro; The Second Declaration of Havana; and Socialism and Man by Che Guevara. Committee members sold thousands of copies of the pamphlets.

The Fair Play for Cuba Committee was open to anyone who opposed U.S. aggression against Cuba. Its members were convinced the best way to counter the U.S. rulers’ assaults was to tell the truth about the revolution.

Solidarity with socialist revolution

When working people and youth in the U.S. learned about the banning of racist discrimination in Cuba, the confiscation of the huge estates of capitalist landlords and the guaranteeing of access to the land for landless peasants, workers control of oil refineries, factories and sugar plantations that were being nationalized, the participation of women in all aspects of society, and more, it solidified their support for the revolution.

Jack Barnes, today national secretary of the Socialist Workers Party, was a student at Carleton College in Minnesota and helped establish a chapter of Fair Play there after visiting Cuba. In Cuba and the Coming American Revolution he describes the impact the committee had on students, workers and instructors on the eve of the U.S.-backed mercenary invasion of Cuba at Playa Girón (Bay of Pigs) in April 1961.

As news came out on April 17 on the beginning of the U.S.-backed assault, right-wingers in the campus cafeteria started chanting “War! War! War!” But when the Cubans defeated the invaders in less than 72 hours the atmosphere rapidly changed.

“Committed builders of the Fair Play for Cuba Committee at Carleton in early 1961 had been fewer than half a dozen. But now came the payoff for the weeks of education, propaganda work, writing, talking, pushing for and organizing open political debate, and taking up the challenges of every opponent on every issue,” Barnes wrote. “As the workers and peasants of Cuba inflicted a crushing defeat on U.S. imperialism, support for the political positions we had been defending exploded overnight. But only because we were there, we were known, and we were prepared to respond.”

At a 1996 meeting to celebrate the political life of Shaw, Barnes explained how the SWP approached its participation in the Fair Play for Cuba Committee. Like revolutionaries they worked with in Cuba, party leaders were committed to the perspective that defense of the Cuban Revolution should be organized without factional bias or exclusion, he said. “No one party should control this work.”

“Surely one of the greatest tests of any political organization is the capacity of its members to participate in mass work with others,” Barnes said, “regardless of diverse points of view, to carry out agreed-on tasks.”

The growing impact of Fair Play did not go unnoticed by the U.S. government and its cop agencies. The committees were accused of being “controlled” by the Socialist Workers Party and the Communist Party. A subcommittee of the Senate Judiciary Committee, headed by notorious segregationist Democratic Sen. James Eastland and liberal Democratic Sen. Thomas Dodd, launched a red-baiting witch hunt against the group, attacks that expanded widely after the assassination of John F. Kennedy.

Shaw was one of those subpoenaed, and like many others, refused to testify about the activities of Fair Play. Despite hours of bullying by Dodd on June 14, 1961, Shaw wouldn’t budge. Near-apoplectic Dodd shouted, “You’re the worst witness I have had in 30 years.”

The Fair Play for Cuba Committee, which dissolved at the end of 1963, told the truth about Cuba’s socialist revolution and widely publicized the words of its historic leaders, winning support among working people and others to end the U.S. economic and political war on Cuba.