On Dec. 1, 1955 — 66 years ago — Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a city bus in Montgomery, Alabama, beginning a yearlong bus boycott. The yearlong fight inspired millions and helped spur the mass Black-led proletarian civil rights struggle that over more than a decade overturned Jim Crow segregation.

This victory transformed attitudes and social relations across the country, and strengthened the unity and fighting capacities of the working class. Nothing short of a social counterrevolution can reverse this mighty demonstration of the power of working people.

Parks, a 42-year-old seamstress, was riding the bus home from her job at a local department store. She was seated in the front row of the “colored section.” By city law, there was an arbitrary movable line that separated the races on the bus, and the drivers were supposed to adjust it to assure all Caucasian passengers got a seat. As the bus filled up, the driver told Parks to give up her seat and stand. She refused and was arrested.

“I was not tired physically. No more tired than I usually was at the end of the working day,” she wrote in her biography. “The only tired I was, was tired of giving in.”

In fact, Parks’ act was a conscious political decision planned out in close collaboration with longtime union and Black rights fighter E.D. Nixon. Nixon was president of the Montgomery division of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters union and had served as president of both the Montgomery and statewide NAACP. Parks joined the local NAACP chapter in 1943 and worked with Nixon as the group’s secretary. After her arrest, Nixon bailed her out of jail and brought in an attorney.

Nixon got on the phone and appealed to church officials and others to come to a meeting to discuss launching a citywide boycott. One of them, Martin Luther King Jr., initially was hesitant, but then agreed to participate. Thousands of flyers were circulated throughout the community calling for a one-day boycott Dec. 5, the day Parks was scheduled to go to trial.

The protest exploded. Some 40,000 Black bus riders joined the boycott. That evening a mass meeting called by Nixon and other Black leaders voted to extend the boycott indefinitely and formed the Montgomery Improvement Association to organize it. King was elected president and Nixon the treasurer.

A determined and heroic fight was organized. Over the next year, both Nixon’s and King’s homes would be bombed. Court indictments were handed down against 90 leaders of the boycott, including several drivers in the car pool formed to provide transportation for those boycotting the segregated buses. Groups of veterans were organized to defend the cars.

Appeal to unions

The Montgomery Improvement Association appealed to unions and other organizations to donate vehicles to the car pool. Providing transportation was crucial to let boycott participants get to work and to shop. Socialist Workers Party members across the country joined in working within their unions to get station wagons donated. One of the first cars delivered was driven down by Farrell Dobbs, a leader of the mighty Teamsters organizing battles in the Midwest in the 1930s, and the party’s candidate for president in 1956.

After going to Montgomery, Dobbs wrote in the April 2, 1956, Militant, “If the Negro people are to win their democratic rights, if the firm alliance of the unions and the Negro movement so imperative for the unionization of the South is to be forged, then the freedom fighters of Montgomery must be supported to the hilt and all the way to their final victory.”

Dobbs recognized the Montgomery fighters from his own experiences. “I have seen nothing like the rank and file outpouring of grievances here since my days in the rising union movement of the Thirties,” he said. “Now as then, a deep well of resentment has been tapped. A burning desire to seek redress has arisen. A growing determination to get action has taken hold.”

As support for the boycott mounted, a Montgomery federal court ruled June 5, 1956, that the law requiring racially segregated seating on city buses violated the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. That amendment, adopted during Reconstruction after the overthrow of slavery through the Civil War, the Second American Revolution, guarantees all citizens equal rights and equal protection under the law.

When the city appealed, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the ruling Nov. 13. Desegregation of the buses was ordered Dec. 20. The boycott ended the following day. It had won after 381 days.

The impact of this powerful, united struggle conducted by tens of thousands of working people in Montgomery roused the interest and support of millions more throughout the country and helped propel the mass civil rights movement forward. Rosa Parks and other leaders became known across the country.

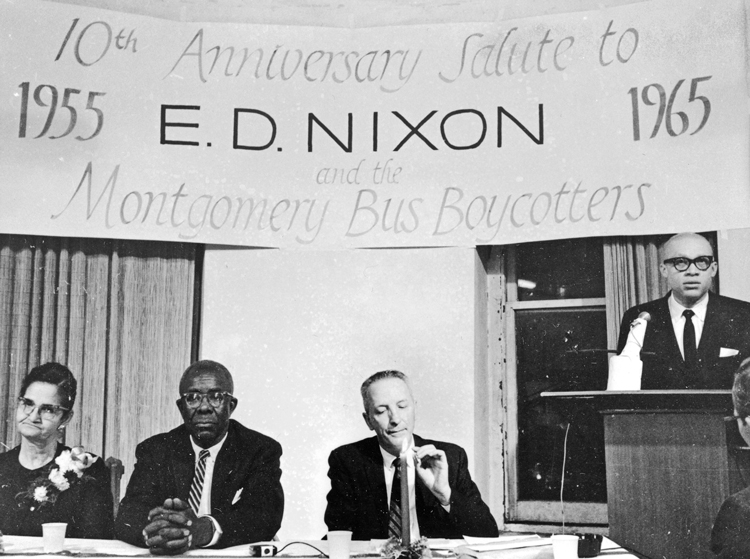

But when a celebration was organized in Montgomery on the 10th anniversary of the bus boycott, organizers didn’t invite Nixon to be part of the program. The Militant Labor Forum in New York invited Nixon and his wife Arlette to come and take part in a dinner and celebration there to honor E.D. Nixon’s leadership role. They joined Dobbs at the head table.

“So you see, the Montgomery Improvement Association was not started just because someone came to town or someone felt it was the proper thing to do at this time,” Nixon told those at the meeting. “It started because there had been a struggle of people for long years.”