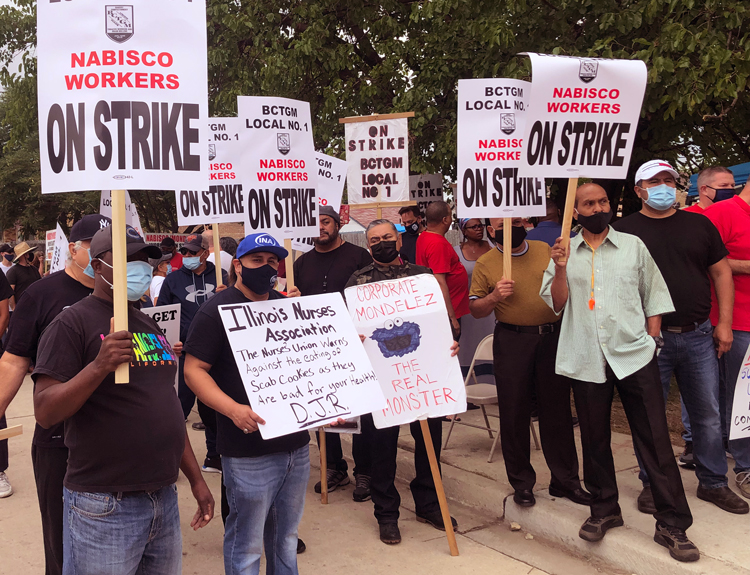

“The concession stand is closed,” United Steelworkers union members told the Militant on the picket lines during their three-month strike against Allegheny Technologies Inc. earlier this year, showing their determination to take on the bosses’ unrelenting drive against our unity, wages, working conditions and dignity. This has been reflected in a growing number of industrial strikes marking 2021.

Each one of these battles is fought out over questions of vital importance to millions of workers — divisive two-tier wages, forced overtime, onerous shift schedules, unsafe working conditions, access to health care and retirement pay, and cost-of-living clauses to combat surging price hikes. Getting out the truth about these struggles and organizing solidarity is crucial in aiding striking workers and in deepening their confidence and fighting capacities.

Workers across the country are watching these struggles, to see if they too can organize and use their unions to fight effectively and win.

“If we don’t stand up, we’re going to get run over,” Karl Brendle, another striking ATI worker in Louisville, Ohio, told the Militant in July. “It’s a good time to get moving now. Bring everyone up with us.”

The number of union battles first began to rise in 2018 with a series of teachers strikes that started in West Virginia. It paused during the imposition of government pandemic lockdowns in 2020 before rising again this year.

The bosses are driven by deepening competition at home and abroad to take steps to defend their markets and profits, and they aim to take it out on our class. But they increasingly find that their “last, best, final offer” is not always “final.” After 2,900 United Auto Workers union members at Volvo Truck in Dublin, Virginia, went on strike in April, they twice voted down proposed contracts before getting one more to their liking in June.

Threats to throw strikers out of their jobs and hire permanent replacement workers did not stop 1,400 workers at Kellogg’s, members of the Bakery, Confectionery, Tobacco Workers and Grain Millers union, from overwhelmingly voting down a contract Dec. 5. Then they voted up an improved version Dec. 18-20.

Locked-out steelworkers at Marathon’s St. Paul Park refinery in Minnesota; strikers at John Deere’s plant in Davenport, Iowa; at Kellogg’s plant in Omaha, Nebraska; and coal miners at Warrior Met in Alabama have all faced court injunctions aimed at restricting their picketing, making it harder for workers to shut down production to force concessions from the bosses.

Bosses at ExxonMobil in Beaumont, Texas, are trying to break the United Steelworkers union. At stake are boss demands for job cuts that would endanger the safety of workers and people living in the area. After locking out workers May 1, they are pushing for a government-run union decertification election.

Two-tier contracts are a central issue in many of today’s strikes. Over decades bosses forced through contracts that impose worse wages, conditions and benefits on new hires, seeking to boost profits while dividing workers doing the same job. Workers counter with demands for “equal pay for equal work.” This was a key issue in the recent strike by the bakery workers at Kellogg’s cereal plants.

Another important issue is the impact of inflation on workers and their families. Real wages, which have declined for decades, are taking a big hit as prices rise at the fastest rate in 40 years, especially on essentials like food, gas and housing. Striking UAW members at John Deere fought successfully to retain cost-of-living protection.

Reversing the decadeslong decline in the number of workers who have contracts with COLA is a key question. And we have to arm ourselves to be able to explain that the bosses’ claim that wage increases cause higher prices is a lie. Rising prices are a way the bosses try to boost their profits at the expense of working people, regardless of what happens to our wages. Explaining this clearly is key to derail their attempts to turn fellow workers against striking unionists.

Workers who don’t yet have a union are also taking action. Last month a well-publicized hunger strike was organized by New York yellow cab drivers to win some relief from the crushing debt the city government has forced on them.

A class-struggle road forward

“At first I didn’t know what it would be like to be on strike. Now I’ve learned about solidarity,” Gerald Lawrence told the Militant on the picket line at Kellogg’s in Memphis, Tennessee, last month. More workers are gaining class-struggle experience and are strengthening bonds with fellow workers as they reach out and win support.

“I’ve learned about our rich history here,” Lawrence added, “going back to the 1968 sanitation workers strike,” part of the Black-led working-class movement that overthrew Jim Crow segregation.

Vital lessons from other working-class struggles can be found in Farrell Dobbs’ four-volume Teamster books. Dobbs was a central leader of the strikes and organizing drives that made Minneapolis a union town and that brought a quarter million over-the-road truckers into the union across the Midwest in the 1930s. He describes how workers with a revolutionary-minded leadership organized to fight, win allies among farmers and others oppressed by capital, and make gains.

He also describes how the powerful rising labor movement was crippled by the class-collaborationist outlook of union officials, who tied the unions to getting out the vote for the Democrats, one of the bosses’ two main political parties.

As working-class struggles grow, “trade union action alone,” Dobbs explains, “will prove less and less capable of resolving the workers’ problems.”

Workers need to organize ourselves independently from the bosses’ parties, their government, cops and courts. We need to build a party of our own, a labor party, based on our unions. As our battles against the bosses get more combative and generalized, we’ll need such a party — and a hardened revolutionary leadership — to take political power and form a workers and farmers government.

Important contract battles lie ahead in 2022, when some 185 major union contracts, covering more than 1.3 million workers, will expire. This includes over 22,000 West Coast dockworkers; 30,000 oil and petrochemical workers across the country; 5,700 members of Steelworkers union members at Goodyear Tire in Virginia; 4,000 Teamster car haulers; BCTGM-organized Frito-Lay workers in Topeka, Kansas, and Vancouver, Washington; and many more.