Ohio’s Ninth District Court of Appeals unanimously upheld a 2019 jury verdict and $31 million award won by the Gibson family, owners of a fifth-generation local bakery and store in Oberlin, against a yearslong race-baiting and defamatory assault by Oberlin College administrators and staff.

The ruling is a victory both for the family and for the rights of all working people.

The March 31 appeals court decision affirmed the decisions of the Lorain County trial court, which heard the lawsuit brought by owners Allyn W. Gibson and son David against the college and Dean of Students Meredith Raimondo.

The Gibsons sued to defend their reputations and business after being smeared as “racists” with a “history of discrimination.”

Oberlin, a town of 8,000, is dominated by the college. It commands an annual tuition fee of $60,243 from its 2,800 students and is ranked 37th on the list of the top 223 National Liberal Arts Colleges. It has an endowment of almost a billion dollars.

Judge Donna Carr, author of the 50-page ruling by the three-judge appeals panel, wrote, “This Court recognizes that this case has garnered significant local and national media attention.”

But, Carr emphasized in dismissing a main argument in Oberlin’s appeal, “the sole focus of this appeal is on the separate conduct of Oberlin and Raimondo that allegedly caused damage to the Gibsons, not on First Amendment rights of individuals to voice opinions or protest.”

Lee Plakas, lead trial lawyer for the Gibsons, said the ruling was “meticulous” in examining and rejecting the college’s appeal.

The ruling gave an overview of the facts in the case based on the trial record.

On Nov. 9, 2016, a student who is Black tried to use a fake ID to buy, and, when that failed, shoplifted wine from the store. When store clerk Allyn D. Gibson, the grandson of the owner, confronted the student, he fled and a physical altercation followed between the male student and two friends waiting outside and Gibson. The police arrested the three students. They eventually entered guilty pleas and were convicted.

The day after the incident and arrests, students organized a protest of several hundred. Carr notes Dean Raimondo and other administrators attended the protest, handed a flyer to a reporter, gave stacks of the flyers to students to distribute, and allowed use of college copiers to produce them. The flyer said Gibson’s Bakery was a “RACIST establishment with a LONG ACCOUNT OF RACIAL PROFILING and DISCRIMINATION.” The college provided coffee, pizzas, and gloves so protesters would not get cold.

The student senate passed a resolution making the same slanderous charge against the Gibsons. The resolution was emailed to all students, Carr wrote, and posted publicly for a year, “easily seen by students, prospective students and their parents, and other visitors to the student center.”

“The potentially libelous statements in this case include much more than calling the Gibsons ‘racists,’” the judge wrote. Given the public’s lack of knowledge of what happened at the bakery, the flyer and resolution “convey to a reasonable reader that the arrest and alleged assault at the bakery were racially motivated, that the Gibsons had a verifiable history of racially profiling shoplifters on that basis for years, and … were a reason to boycott the bakery.”

Damage done to the Gibsons

Dean Raimondo later instructed the college’s catering vendor to cancel the Gibsons’ longstanding contract to supply baked goods to the campus, a source of the bakery’s revenue. According to trial testimony, Carr noted, “Oberlin would not direct Bon Appetit to resume business with the bakery unless the Gibsons agreed to drop criminal charges against the student shoplifters” and give first-time student shoplifters a “pass.”

“The Gibsons also presented evidence,” Carr wrote, “that they had been continually taunted and harassed for many months, that their business and property had been vandalized, and that Grandpa [Allyn W.] Gibson had broken his back after an encounter with someone he believed was trying to harass him or break into his apartment.”

People who knew the Gibsons testified “they had never witnessed any incidents of racism or racial profiling” by the bakery owners. In contrast, the college presented nothing but hearsay about what the school’s administrators said they “heard” about the Gibsons’ alleged racism. The appeals court affirmed the trial court’s decision to not admit that testimony.

“This case has a lengthy history,” Judge Carr wrote about one of the longest trials in Lorain County’s history, noting the 14,417 hours the Gibson lawyers spent on the case and affirmed that the trial court had not abused its discretion in awarding the Gibsons $6,271,395 for legal fees.

The Gibsons filed a cross appeal to restore about another $15 million in damages cut by the trial judge due to state laws capping damages in such cases. The Gibsons argued the cap was unconstitutional and a violation of the jury’s rights. The appeals court rejected this appeal.

Gibsons won wide support

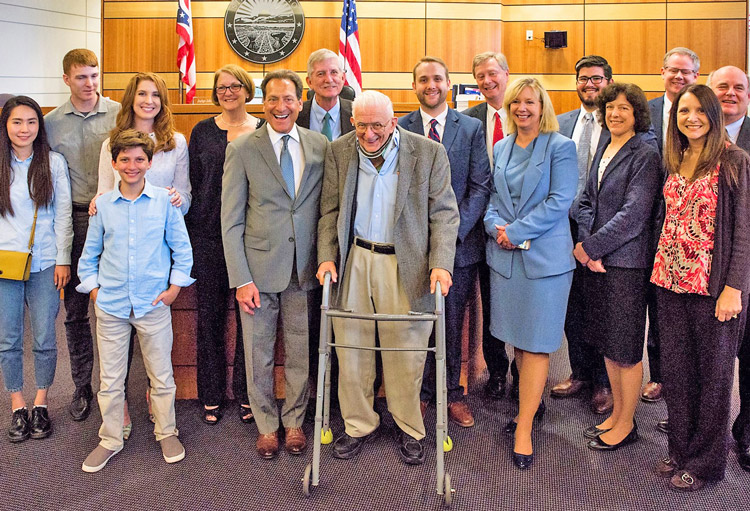

Since the 2019 trial, Allyn W. Gibson and his son David died and other family members stepped in to continue the fight and keep the bakery open.

“Without community support we wouldn’t have won,” Allyn D. Gibson, the grandson, told the Militant in 2019. Working people in the area supported the Gibsons by visiting and spending money at the store after the student protests began and by displaying “Support Gibsons” lawn signs.

The Gibson family’s refusal to buckle under to the college and their determination to defend themselves resonated with many working people nationwide who reject race-baiting and the entitled upper-class attitudes revealed in the actions of a billion-dollar institution and its students.

Plakas told the Cleveland Jewish News April 1, “The Gibsons hopefully now have a pathway and window to survive because from their perspective the animosity of the college and the students continues and the business of the Gibsons has been severely compromised since the verdict.”

The college said in a statement it was “reviewing the Court’s opinion,” before deciding whether to appeal the ruling to the Supreme Court of Ohio.