Sixty-one years after African anti-imperialist independence fighter Patrice Lumumba was assassinated, a gold-crowned tooth, the only part of his body that exists, was buried in a state funeral in the Democratic Republic of the Congo June 30. The date marked the 62nd anniversary of the central African country winning independence from Belgium colonial rule.

Lumumba set an example as a determined fighter against imperialist exploitation and oppression. Thousands gathered along the streets in Kinshasa to pay their respects to the leader who led the fight for the country’s independence and was its first prime minister.

Belgium-backed secessionist forces executed Lumumba on Jan. 17, 1961, with the full backing of Washington. Belgian authorities promptly dissolved and dismantled his body in sulphuric acid, fearing his grave would become a rallying site for those in the Congo and elsewhere fighting against exploitation, oppression and the legacy of colonial rule. The Belgian policeman who oversaw the body’s disposal took the tooth, which he kept in his home for decades.

In a mockery of what Lumumba fought for, attending the funeral was the foreign minister of Belgium, alongside the current presidents of the Democratic Republic of Congo and neighboring Congo Republic and several African ambassadors. Earlier that month Belgium’s King Philippe visited the Democratic Republic of Congo for the first time and admitted Belgium’s colonial rule was unjustifiable and racist, but refused to apologize for it.

Who was Lumumba? Why did he evoke the ire of Washington and other imperialist powers? What can working-class fighters learn from him today?

Independence fight in Congo

At the 1885 Berlin conference, where European powers carved up most of Africa among themselves, Belgian King Leopold II was allotted sole authority over the Congo. According to a Belgian government commission estimate, between the late 1870s and 1919 some 10 million people in the Congo died as a result of Belgium’s colonial brutality.

In October 1958, Lumumba, a former postal employee, helped to found the Congolese National Movement, the first nationwide Congolese political party. At the time, Congo was among the world’s largest producers of copper, uranium, cobalt, industrial diamonds and rubber. Belgium, France, England and U.S. companies were determined to maintain the oppressive living and working conditions of toilers there to reap superprofits off their backs.

As support for independence grew, Belgian authorities felt increasing pressure to appear to agree to independence, setting a date of June 30, 1960. All the while they intended to find a way to keep control over the peoples and resources of the country.

At the ceremony celebrating the event, Lumumba, who was not scheduled to speak, took the podium. His talk, broadcast on radio, electrified the population.

“No Congolese worthy of the name can ever forget that we fought to win” independence, Lumumba said, “a fight in which there was not one effort, not one privation, not one suffering, not one drop of blood that we ever spared ourselves. We are proud of this struggle amid tears, fire, and blood, down to our very heart of hearts, because it was a noble and just struggle, an indispensable struggle if we were to put an end to the humiliating slavery that had been forced upon us.

“The wounds that are the evidence of the fate we endured for 80 years under a colonialist regime are still too fresh and painful for us to be able to erase them from our memory,” he said. “Back-breaking work has been extracted from us, in return for wages that did not allow us to satisfy our hunger, or to decently clothe or house ourselves, or to raise our children.”

Malcolm X on Lumumba’s example

Malcolm X, speaking at the first public rally of the Organization of Afro-American Unity on June 28, 1964, hailed Lumumba’s example. “He didn’t fear anybody,” Malcolm said. “They couldn’t buy him, they couldn’t frighten him, they couldn’t reach him. Why, he told the king of Belgium, ‘Man, you may let us free, you may have given us our independence, but we can never forget these scars.’”

Led by Washington and Brussels, the imperialist powers stepped up efforts to get rid of Lumumba. The CIA was plotting his assassination as “an urgent and prime objective,” wrote then CIA Director Allen Dulles, in documents made public in a 1975 U.S. Senate report.

Less than two weeks after Congo’s independence, Brussels organized a secessionist movement in the country’s province of Katanga, where U.S. and European companies had vast mineral holdings. On July 11, 1960, Moise Tshombe, a wealthy businessman, declared Katanga’s separation from the Congo. The Belgium government then sent 10,000 troops to Katanga to protect the secessionists.

Lumumba then made a fatal error. He requested United Nations “peacekeeping” troops be sent to the Congo. A force of 8,000 was rapidly dispatched there by the end of July. U.N. troops stood aside as pro-U.S. forces ousted Lumumba from the government in a coup led by Army Chief of Staff Col. Joseph Mobutu in September 1960. U.N. occupying forces then closed down government radio stations supportive of Lumumba and disarmed forces loyal to him.

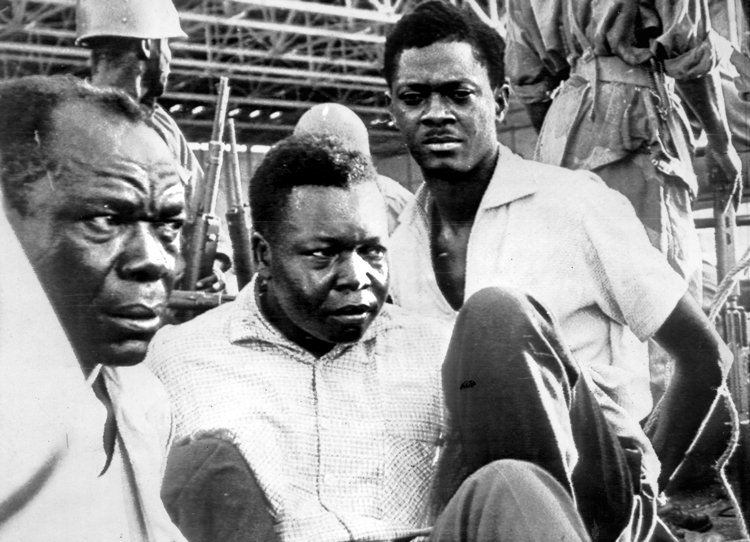

Lumumba was arrested and turned over to Tshombe’s forces who executed him.

Speaking to workers at the opening of the Patrice Lumumba sulphate metals factory in Pinar del Río, Oct. 29, 1961, Cuban revolutionary leader Che Guevara discussed the lessons to be learned from this fighter against imperialist rule.

“He thought that, armed only with the naked truth, not backed up by physical weapons, by an entire armed people, that it was possible to fight against everything belonging to the past,” Guevara said. “They murdered him because they knew he could not be bought off. They murdered him because he was an authentic expression of his people. They murdered him because he was a popular hero.”

In a December 1964 address to the U.N. General Assembly, Guevara said, “How can we forget the betrayal of the hope that Patrice Lumumba placed in the United Nations? How can we forget the machination and maneuvers that followed in the wake of the occupation of that country by United Nations troops, under whose auspices the assassins of this great African patriot acted with impunity?”

In an interview with Radio Havana in August 1987, Thomas Sankara, leader of the popular revolution in Burkina Faso and the country’s president, commented on the importance of Patrice Lumumba.

“Patrice Lumumba is a symbol. When I see African reactionaries who were contemporaries of this hero and who were unable to evolve even a little upon contact with him, I see them as wretched, despicable people who stood before a work of art and did not even manage to appreciate it.

“He grew up under conditions in which Africans had practically no rights whatsoever,” Sankara said. “Largely self-educated, Patrice Lumumba was one of the few who learned more or less how to read and managed to become conscious of the situation of his people and of Africa.”