Russian President Vladimir Putin is amassing forces in preparation for a deadly spring offensive in the Donbas region of eastern Ukraine. The Ukrainian military, backed by volunteers, is preparing to repulse Moscow’s attacks and launch a counter-offensive.

Putin claims his war in Ukraine aims at defeating “Nazism,” like Stalin’s was against fascist Germany in World War II.

His accusation stands reality on its head. The government in Ukraine is similar to other liberal capitalist regimes around the world. In Germany the fascists were funded and promoted by the capitalist class to crush a rising working-class movement, smash the unions and murder millions of Jews. By trying to conquer Ukraine today, Putin is seeking to destroy its independence and regenerate the prison house of nations that existed under the czarist empire, not fight “fascism.”

After suffering significant defeats in Ukraine, Putin has shifted to a murderous bombardment of civilian populations and key infrastructure, reminiscent of the firebombing of Dresden, Germany, and Tokyo by London and Washington in the second imperialist world war.

Civilian fighters play a key role in Ukraine’s air defenses. As air raid sirens sound, volunteer units of working people rush to the top of high-rise buildings or into fields to monitor the skies. They shoot down many of the slow-moving drones, using Soviet-era heavy machine guns that they’ve adapted.

Tens of thousands of Russian troops are gathering in eastern Ukraine for a major offensive. Conventional forces are reinforcing the Wagner Group mercenary militias that Moscow is using. They have suffered heavy losses, employing “human wave” assaults that have led to thousands of deaths. There are up to 50,000 Wagner fighters in eastern Ukraine. They are largely “recruited” from inmates across Russia’s prison system by offers of pay and an amnesty if they survive combat.

Russian objectors to Putin’s war

After seeing the horrors that Putin’s war inflicts on Ukrainians and on Russian soldiers, Andrei Medvedev, a Wagner platoon officer, deserted and escaped on foot to Norway, where he is seeking asylum. Former convicts recruited to the militia are “sent to the front line like cannon fodder,” he told the Moscow Times.

Medvedev reported seeing two prisoners shot “in front of others for refusing to follow orders.” He said, “there were a lot of such cases.”

Konstantin Yefremov, a former lieutenant in Moscow’s army, told the BBC he was repulsed by seeing mistreatment and torture of Ukrainian prisoners of war by senior Russian officers. He and his men tried to smuggle cigarettes and food, as well as hay to sleep on, to their captives.

When Yefremov tried to resign, he was denounced as a coward and a traitor by a top officer. Eventually he was dismissed for refusing to return to fight in Ukraine and had to flee Russia. He told reporters he wanted to apologize to “the entire Ukrainian nation for coming to their home as an uninvited guest with a weapon in my hands.”

Olesya Krivtsova, a university student from the northern Russian city of Arkhangelsk, is facing more than 10 years in a penal colony for opposing the war. She is accused of “justifying terrorism” and “discrediting the Russian armed forces.”

Krivtsova was added to a list of supposed terrorists and extremists by the Russian government. Her crime? She posted pictures of Ukrainian civilians killed by Moscow’s forces. In particular, she circulated recommendations from Kyiv aimed at Russian soldiers explaining how they could surrender.

More than a million Russians, conscript-aged men or their close relatives, have contacted the Ukrainian army’s “I Want to Live” project since Putin called up 300,000 new draftees in September.

Across Russia other opponents of the war are also being prosecuted.

Anti-war “flower protests” have spread as people continue to set up memorials for the dozens of Ukrainians killed in the Kremlin’s missile strike on a Dnipro housing block last month, one of the deadliest single incidents of Moscow’s invasion.

‘Flower protests’ in Russia

Displays of flowers, stuffed toys, pictures of the destroyed high-rises and handwritten notes have sprung up at multiple sites in at least 60 cities. Some are placed alongside statues of Ukrainian literary figures like Taras Shevchenko, Lesya Ukrainka and Nikolai Gogol. Others are laid at monuments to victims of Soviet-era political repression.

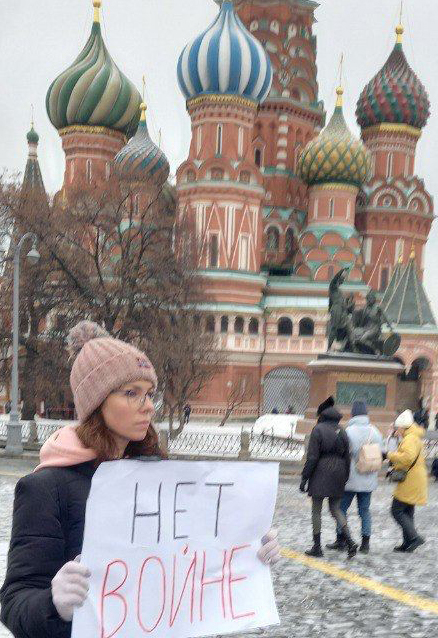

Anti-war graffiti and stickers are appearing on Russian streets. Solitary individuals hold placards demanding “Peace to Ukraine! Freedom for Russia!” or “No to war!”

“It’s a statement against the war, not just mourning for the dead people in Dnipro,” one woman laying flowers at a memorial in the Siberian city of Novosibirsk, told the Moscow Times. “I couldn’t stay silent.”