MOUNT OLIVE, N.J. — “My father inherited his family’s debts, then we inherited his,” Hunter Hildebrant, 25, told the Militant at her family’s farm Feb. 18. Together with brothers Roy and Forrest, and twin sister Aspen, she grows tomatoes, onions, peppers, strawberries, blueberries, pumpkins and flowers on 56 acres that have been in the family for four generations.

Their father died in 2012 when Hunter was 15. “Teachers gave us half days off school, calling it a ‘work-study program,’ so we could keep the farm going.”

They rapidly discovered the challenges that lay ahead.

The farm had a lien on it, a claim “by someone we never met who lived thousands of miles away,” who could seize their property if the Hildebrants failed to make debt payments. “We had to pay off $25,000 a year for several years,” she said. “It might not sound like a lot, but it was to us.”

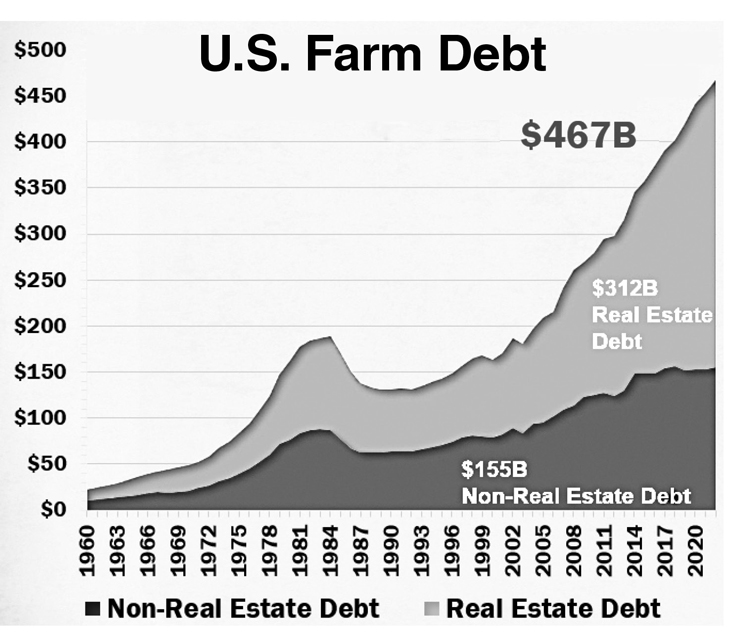

Very few working farmers can stay on the land without having to take out loans. Average farm debt reached a record high in 2020, after rising steadily for three decades. At the same time, farm incomes are expected to fall again this year, the Department of Agriculture projects, increasing the debt burden farmers face.

While workers are exploited directly by their bosses, working farmers are squeezed by the high interest rates banks and other lenders charge and the prices for inputs — seed, feed, fertilizer and farm implements — on the one end, and the low prices offered by monopoly processing companies and supermarket chains on the other.

Hunter Hildebrant took a job as a janitor at a community college, which also allowed her to study horticulture without paying tuition. “I didn’t finish the course, but I learned a lot.” Today she works on the farm, as well as at a large commercial greenhouse, and is looking for a third job.

Aspen also works two jobs. Like many working farmers, while putting in long hours on the land they also have to work other jobs to try and make ends meet.

Friends and fellow farmers helped out. Because of the high prices today and their impact on the finances of working people, “they aren’t buying flowers like they used to,” she said. And last year the Hildebrants’ wells ran low. “Without enough water we had to throw out produce that had withered.”

“Diesel prices have almost doubled since the pandemic,” she said, pointing out they depend on the fuel to run tractors and to keep three greenhouses warm enough to cultivate seedlings.

“We have a ‘tractor graveyard’ on the farm. My brothers improvise. They take parts off the old tractors to keep the two we run going.” They often face unexpected expenses. The truck Hunter uses to take their produce to local markets now needs to be replaced.

As well as selling what they grow at a farm stand and farmers markets, they also supply a wholesaler. “But we have no say over the prices we get from the wholesaler.”

To preserve crops from pests “we can shoot rabbits, but to get rid of weeds we need herbicides,” Hunter said. While inflation now runs at 6.4% annually, the cost increase for crucial farm inputs like diesel, seeds and herbicides is much higher. Some herbicides have skyrocketed as much as 300% since the end of the pandemic. That’s all part of a setup in which all the risks are taken by working farmers, while the agricultural monopolies reap vast profits.

“Initially I was wary about talking to socialists,” Hunter said as we were leaving the farm. “I’m a Republican voter.”

“Workers and working farmers face a common enemy,” I said, pointing to the strikes and other union struggles taking place today. “We need to organize independently of the bosses and their two political parties.”

She invited us to come back and talk some more.

Roy Landersen contributed to this article.