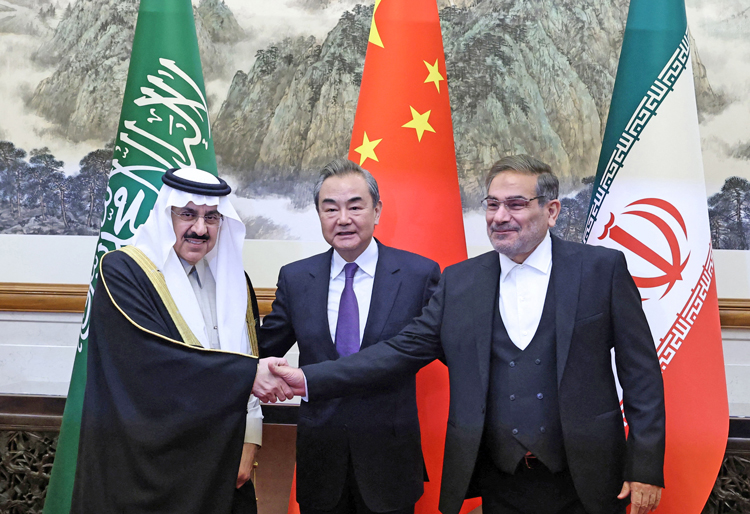

The reestablishment of diplomatic relations between the Iranian and Saudi regimes — finalized in Beijing — is a reflection of the weakening of Washington’s role in the Middle East, although it remains the dominant imperialist power intervening there.

The ruling classes in Tehran and Riyadh have been rivals for decades, but their relations further deteriorated after the popular 1979 overthrow of the U.S.-backed dictatorship of the shah in Iran and then the consolidation of a cleric-led capitalist counterrevolution there by 1983. They broke relations in 2016.

The reactionary regime in Iran paints itself as the defender of Shiite Muslims against Sunni-led regimes and U.S. imperialism. The monarchy in Saudi Arabia defends the interests of a mostly Sunni merchant, banking and oil-rentier ruling class.

Pressured by today’s deepening capitalist crisis, Washington’s sanctions and mass resistance inside Iran, the rulers there hope to break out of their isolation.

The Saudi monarchy is no longer convinced it should continue relying solely on the U.S. rulers’ military might to protect its interests.

Saudi Arabia’s rulers sell at least five times as much oil a day to China than to the U.S. But Beijing’s military weight in the region, with just one base in Djibouti, pales in comparison to U.S. bases in at least 10 countries there and tens of thousands of troops.

Tehran and Riyadh back opposing sides in Yemen’s civil war. The deal is aimed at tamping down the conflict. Tehran has been arming Houthi rebels, who control the capital and use drones to strike oil production inside Saudi Arabia. A Saudi-led coalition has carried out years of devastating bombings in Yemen trying to restore the previous government.

More than 350,000 died in the war, including many from starvation. Millions more have faced famine and disease. Today 80% of the population depends on foreign food aid. On April 9 Saudi officials met with Houthi representatives to discuss a cease-fire.

Elsewhere in the region, regimes that had shunned Syrian President Bashar al-Assad for over a decade are discussing inviting a Syrian representative to next month’s Arab League summit. This would be the first time since the beginning of Syria’s civil war, which erupted after Assad tried to crush a popular uprising. Military intervention by Moscow and Tehran enabled the Assad regime to retake swathes of the country. Washington continues to impose sanctions on Syria.

Tehran claims the deal with Riyadh signifies the death of the “Abraham Accords” — the establishment of diplomatic relations between the Israeli government and the governments of the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Kosovo, Morocco and Sudan — signed in 2020. The agreements were brokered by the administration of President Donald Trump with the behind-the-scenes backing of the Saudi regime.

The accords ended the seven-decades-long boycott of the Jewish state by a number of Muslim and Arab governments, imposed on the pretext of defending the Palestinian people. While Trump’s goal was more stability for U.S. capitalism in the Middle East, the accords widened openings for working people of different religious beliefs and national origins to travel, work side by side and find ways to join together to defend their class interests.

President Joseph Biden has shown little interest in expanding the number of Arab governments recognizing Israel. He scaled back Washington’s support for the Saudi-led war in Yemen and took the Houthis off its list of alleged terror groups. But the accords remain in place and an Israel-UAE free trade agreement was finalized in early April.

To consolidate their power, the Iranian rulers have extended their counterrevolutionary influence, directing militias and political parties in Iraq; training and arming Hezbollah in Lebanon; backing Hamas in Gaza; and stationing forces in Syria. Emboldened by the deal with the Saudis, they’re stepping up threats of war against Israel, which they vow to wipe off the face of the earth.

On April 6 Hamas forces based in southern Lebanon launched more than 34 short-range missiles at Israel, causing damage but no deaths. Hamas also launched missiles from Gaza and a pro-Iranian militia in Syria fired rockets at the Golan Heights. The Israeli government retaliated, making sure not to strike any Hezbollah targets in Lebanon.

Unlike Hamas in Gaza, which has rudimentary missiles, Hezbollah possesses more than 100,000, many of them precision-guided. So far it has not gotten directly involved in recent attacks on Israel. It is part of the ruling coalition government in Lebanon that has faced resistance by working people of all religions amid a deepgoing economic and financial crisis.

The Israeli government has said repeatedly that if the Iranian rulers’ nuclear program advances to building a nuclear weapon, it will launch an attack to eliminate the threat.

The most important curb to this danger is the sea change in attitudes toward the regime in Iran since working people there joined protests in 2018 and 2019, propelled by opposition to Tehran’s military and political interventions, and again last year after the death of Zhina Amini following her arrest by the hated morality police.

A war with Israel would not be popular in Iran. Already in April there have been dozens of protests by retirees, strikes by nurses and oil workers and more, including weekly actions in Baluchistan calling for freeing all political prisoners and equal rights for oppressed minorities.