Riding a high approval rating amid widespread crime from his “war on gangs,” President Nayib Bukele of El Salvador is paving the way for reelection in 2024 despite a constitutional prohibition on serving a second term. On May 10, Bukele claimed his government had accumulated 365 days without murders since he took office in 2019. He contrasted it to 2015 when there were over 6,600 homicides in El Salvador.

For years the lives of working people have been torn asunder by criminal violence, and they see little option except to choose between that chaos and a “lesser evil” as Bukele’s government cracks down, accompanied by the suspension of constitutional rights and civil liberties.

In March 2022, following a spate of killings, Bukele’s administration declared a “state of emergency” and curtailed freedom of assembly, rights and protections of the accused. He also lifted bans on cops spying — without a court order — on phone calls and mail of anyone authorities deem a suspect. Initially presented as a temporary measure, the government has extended it 14 times and vows to continue the measure “until every gang member is in prison.”

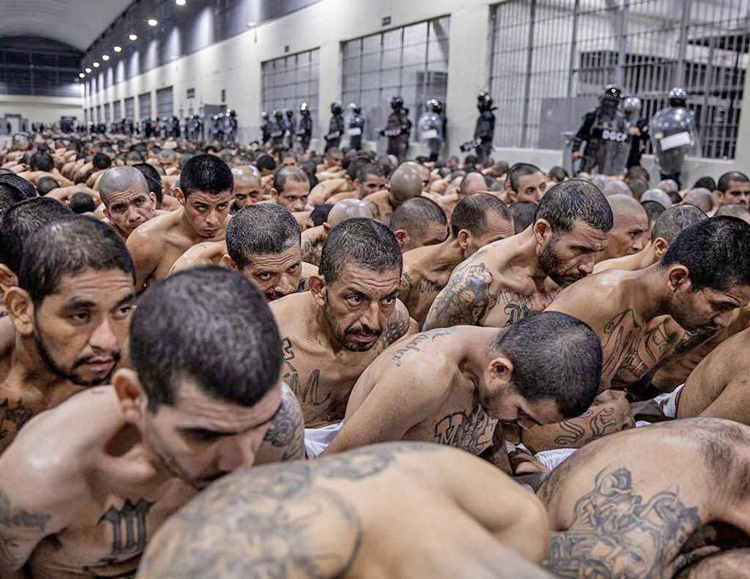

More than 68,000 people have been arrested. Thousands of heavily armed troops and cops have sealed off and swept through working-class neighborhoods seizing “suspects.” Along with gang members, however, thousands have been arbitrarily arrested and held for months awaiting trial.

“It’s an injustice,” Lilian Laínez told CNN May 11, standing in front of a local jail where she and dozens of others demanded the release of their incarcerated relatives. “They’re taking them without saying a word.”

Others interviewed by the press said relatives who have been convicted of previous offenses and served their time are also being detained. Some said they’ve had to pay bribes of $1,000 or more just to visit them.

The Ministry of Justice announced it has released some 5,000 people, more than 7% of those arrested, admitting they had no gang affiliation.

Rise of Bukele

Bukele has exploited a wave of discontent with the two traditional parties — the conservative National Republican Alliance (ARENA) and the formerly revolutionary Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN). They have alternated in power since 1992, at the end of the country’s 12-year civil war.

He is a product of the deepening crisis for working people, as the capitalist rulers have proved incapable of alleviating the scourge of unemployment, inflation and crime. Bukele portrays himself as an outsider, standing up against the “same old” corrupt politicians he tries to blame for the grim living conditions workers face.

“There’s enough money to go around as long as no one steals,” is one of Bukele’s favorite demagogic catchphrases. He seeks to obscure the fact that the biggest thieves of the wealth produced by working people are the capitalist rulers, and that he has no intention of interfering with their system of exploitation and oppression.

Bukele is a businessman who comes from a leftist family. He rose out of the ranks of the FMLN, elected mayor first of a small town in 2012 and then of San Salvador, the country’s capital, in 2015. Expelled by the FMLN in 2017, he became the presidential candidate of the Great National Alliance (GANA), a conservative capitalist party that is also widely discredited.

Like other elected capitalist officials in Latin America today, Bukele has gone after the press, as well as non-governmental organizations critical of his administration, and has concentrated power in the executive branch. Following last year’s legislative election in which his new party, Nuevas Ideas (New Ideas), gained a two-thirds majority in Congress, his administration replaced five Supreme Court justices and the attorney general. This is cause for concern among ruling circles who would rather maintain a semblance of bourgeois democracy and stability.

Target is working people

The real target of Bukele’s war on crime, as well as the “alternative solutions” proposed by his opponents, is working people, even if for many it seems to be lowering the devastating level of violence.

Trade unionists, environmental activists, and defenders of democratic rights have condemned recent arrests of protesting workers. In January, a municipal workers’ protest in Soyapango was broken up by the police. They were demanding unpaid wages and bonuses, and proper tools, shoes and uniforms.

“Let them go!” yelled other protesters and bystanders in a video. One can be heard calling out, “Are these the ‘new ideas?’”

The ruling class uses the police and armed forces to keep workers in line and put down working-class resistance as the class struggle heats up. This is something fresh in the minds of generations in El Salvador.

The late 1970s and early 1980s saw a rise in workers strikes, factory occupations, and fights by landless peasants and the rural poor, coupled with university and school occupations. The forces behind the FMLN of that day participated and helped advance these struggles. As the struggles took more of a political and revolutionary character, and began to threaten capitalist rule, they were met with brutal repression by the government, backed by Washington.

There are no struggles on that scale today, and the FMLN is just another capitalist electoral party. But new class battles will certainly come as the capitalist economic and social crisis deepens.